Musica bardica: cos’è?

Nel nostro immaginario, influenzato dalle visioni romantiche ottocentesche, il bardo è un poeta cantore delle tradizioni del popolo celtico. Difatti con la sua musica bardica mette per iscritto l’identità di una nazione, nonché strenuo difensore delle peculiarità di un popolo. Inoltre lo visualizziamo mentre accarezza la sua arpa bardica, lunghi capelli fluenti e abiti svolazzanti nel vento.

In realtà l’antico bardo ripudiava la scrittura e preferiva affidare tutta la sua conoscenza solo alla memoria.

Detto questo esistono ancora i bardi e qual’è la musica bardica oggi?

[English translation]

Who were the bards and how was the bardic music?

In our imagination, influenced by nineteenth-century romantic visions, the bard is a poet who sings the traditions of the Celtic people, defender of the identity of a nation.

Moreover we visualize him, while he caresses his bardic harp, long flowing hair and clothes fluttering in the wind.

The ancient bard really repudiated writing and preferred to entrust all his knowledge only to memory.

Having said that, there are still bards and what is bardic music today?

SOMMARIO

Druido-bardo

I am the son of poetry

IRLANDA

Mecenati di stirpe celtica

Il bardo irlandese errante

I bardi irlandesi nel 1700

Turlough O’ Carolan

Belfast Festival 1792

Edward Bunting

SCOZIA

Ciclo feniano (James MacPherson)

Carmina Gadelica (Alexander Carmichael)

BRETAGNA

La rinascita dell’arpa in Bretagna

I TEMI DELLA MUSICA BARDICA

Gli Eroi

Cara Terra

Aisling

A-Z Musica bardica tradizionale

Poesia bardica contemporanea

Il Druido Poeta

Nell’età del Ferro il Bardo era partecipe del sacro all’interno dell’ordine sacerdotale, un druido-poeta, ponte tra l’umano e il divino, teso alla conoscenza e sul sentiero della comprensione profonda dell’esistenza.

Il bardo sapeva vedere dentro alle cose, coglierne gli aspetti più profondi in termini spirituali, in armonia con gli elementi, la natura e nell’equilibrio di anima, spirito e corpo.

“Io sono il figlio di Poesia,

Poesia, figlia di Riflessione,

Riflessione, figlia di Meditazione.

Meditazione, figlia di Credenza

Credenza, figlia di Ricerca.

Ricerca, figlia di Grande Conoscenza,

Grande Conoscenza, figlia d’Intelligenza.

Intelligenza, figlia di Comprensione,

Comprensione, figlia di Saggezza.

Saggezza figlia dei tre Dei di Dana”

Il bardo Nede – “Dal colloquio dei due Saggi” ( Nede from “The Colloquy of Two Sages”)

The Druid-bard

In the Iron Age the Bard was a druid-poet, a bridge between the human and the divine, aimed at knowledge and on the path of profound understanding of existence.

The bard knew how to see things inside, grasp the most profound aspects in spiritual terms, in harmony with the elements, nature and in the balance of soul, spirit and body.

I am the son of Poetry..

I am the son of Poetry.

Poetry, daughter of Scrutiny

Scrutiny, son of Meditation.

Meditation, daughter of Great Knowing

Great Knowing, son of Seeking.

Seeking, daughter of Investigation

Investigation, daughter of Great Knowing.

Great Knowing, son of Great Good Sense

Great Good Sense, son of Comprehension.

Comprehension, daughter of Wisdom

Wisdom, daughter of the three gods of Dana.

IRLANDA

IRLANDA

Mecenati di stirpe celtica

Nel Medioevo con il diffondersi del Cristianesimo anche in Irlanda l’ordine druidico scomparve, e i Bardi diventarono poeti di professione alle dipendenze dell’aristocrazia. Tenuti in grande onore e ancora ricchi di privilegi, iniziarono una lenta decadenza di pari passo con la perdita di potere dei loro mecenati di stirpe celtica.

Karin Leitner – Flute, Cormac de Barra – Harp

Enrico VIII re d’Irlanda

Quando nel 1541 Enrico VIII si proclama re d’Irlanda, il potere socio-culturale passa alla nuova nobiltà inglese trapiantata in terra irlandese. La guerra contro gli inglesi aveva portato a tremendi massacri e Cromwell tra il 1598 e il 1652 quasi dimezza la popolazione dell’isola.

Così che nel Seicento, la musica dei bardi esorta all’unità i clan irlandesi, spesso in discordia tra loro, per combattere contro gli inglesi. Ma già il declino si fa sentire

E il bardo MacMahaon dice al figlio:

“Figlio mio, non coltivare l’arte dei versi,

abbandona del tutto la professione degli avi;

benchè abbia diritto al primo degli onori,

la poesia da oggi in poi è presagio di miseria.

Non abbracciare il peggiore dei mestieri,

non comporre più canti irlandesi!“

Celtic ancestry patrons

In the Middle Ages, with the spread of Christianity, even in Ireland, the Druidic order disappeared, and the Bards became professional poets employed by the aristocracy. Held in great honor and still full of privileges, they went hand in hand with decadence of their Celtic ancestry patrons.

HENRY VIII KING OF IRELAND

When in 1541 Henry VIII proclaimed himself king of Ireland, the socio-cultural power passed to the new English nobility transplanted into Irish country. The war against the British had led to tremendous massacres and Cromwell from 1598 to 1652 almost halves the population of the island.

So that in the seventeenth century, the bardic music calls on the Irish clans to unity, often in disagreement with each other, to fight the British.

But the decline is almost near!

Il bardo irlandese errante

La musica bardica irlandese era una tradizione peculiare, ma non del tutto impermeabile alle influenze esterne. Infatti accolse lo stile musicale del “concerto veneziano” così di moda nell’ambiente nobile irlandese tra il XVII e il XVIII° sec. E Turlough O’ Carolan (1670 – 1738) ne fu il massimo esponente.

![]() [L’arte immortale di Turlogh O’Carolan (Flavio Poltronieri)]

[L’arte immortale di Turlogh O’Carolan (Flavio Poltronieri)]

La musica di Turlogh O’Carolan: una discografia essenziale

Patrick Ball – O’Carolan’s Farewell to Music (Fortuna Records, 1992)

Derek Bell – Carolan’s Receipt (Claddagh, 1986)

Derek Bell – Carolan’s Favourite (Claddagh, 1988)

The Chieftains – The Chieftains 9: Boil the Breakfast Early (Claddagh, 1979)

Simon Mayor – Carolan. Fantasies On Themes By Turlough O’Carolan (Acoustics, 2023)

Máire Ní Chathasaigh – The Harp of Turlough O’Carolan (Old Bridge Music, 1987)

Maire Ni Chathasaigh and Chris Newman – The Carolan Album (Old Bridge Music, 1991)

The Harp Consort – Andrew Lawrence-King – Carolan’s Harp (BMG/Deutchse Harmonia, 1996)

Diventato musicista errante il Bardo irlandese si avvicina al popolo e lo esorta alla rivolta, difendendo i costumi e le tradizioni celtiche. E così la poesia e la musica bardica crebbero insieme alle modalità e ai suoni della gente comune.

Le Penal Laws in Irlanda

Dopo le Penal Laws (1695) e l’ostinato ostracismo verso la lingua e le usanze irlandesi, alla fine del Settecento il numero degli arpisti si contava sulla punta delle dita.

Irish bardic music was a peculiar tradition but not completely impervious to external influences. In fact it welcomed the musical style of the “Venetian concert”, so fashionable in the Irish noble environment between the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

And Turlough O ‘Carolan (1670 – 1738) was its greatest exponent.

However, becoming a wandering musician, the irish Bard approaches the common people and exhorting to revolt, defending the Celtic customs and traditions. And so poetry and bardic music grew together with the modes and sounds of common people.

Penal Laws in Ireland

After the Penal Laws (1695) and the stubborn ostracism towards the Irish language and customs, at the end of the eighteenth century the number of harpists was counted on the fingertips.

I bardi irlandesi nel 1700

Le composizioni musicali più antiche giunte fino a noi sono state trascritte dai bardi irlandesi alla fine del 1500, la maggior parte di queste musiche però sono andate perdute, perché erano tramandate oralmente da maestro ad allievo. A partire dall’Alto Medioevo l’arpa viene eletta a strumento privilegiato del Bardo ed è detta bardica a sottolineare il connubio raggiunto tra i due.

L’ordine bardico irlandese si “estingue” nel XVIII° sec e già da subito qualche filantropo si ingegnò ad organizzare degli incontri (concorsi, balli, festivals) per trascrivere le melodie e conservare per i secoli futuri una vivida testimonianza dell’eredità dei Bardi.

Belfast Festival 1792

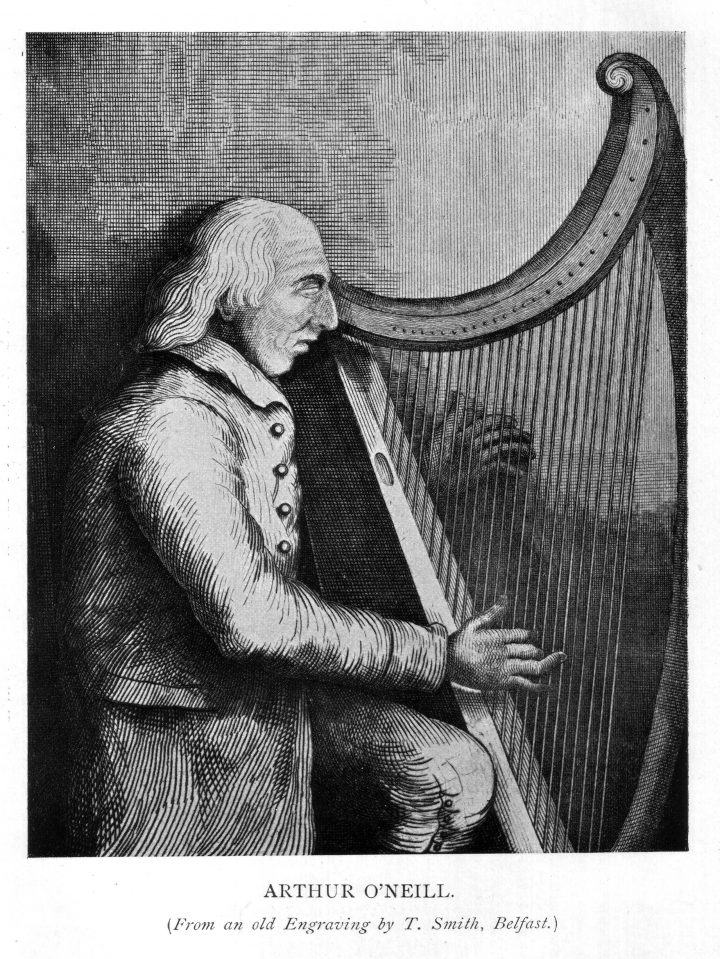

Il primo di questi incontri si tenne a Belfast nel 1792 nel mese di luglio, a cui si presentarono solo una decina di arpisti, il più giovane aveva 15 anni e il più anziano, Denis Hempson ne aveva 97.

Hempson in quell’occasione suonò ancora alla vecchia maniera, pizzicando le corde con le unghie e appoggiando l’arpa sulla spalla sinistra – con le mani che si muovevano all’inverso rispetto alla tecnica più moderna.

L’eredità di Edward Bunting

Edward Bunting venne incaricato di trascrivere i brani eseguiti dagli arpisti nei 4 giorni del festival e il suo entusiasmo fu tale che non smise più per tutta la vita. Così pubblicò tre raccolte di musica, nel 1797, 1809, e 1840.

Il pregio del lavoro di Bunting, fu quello di aver raccolto molte informazioni storiche, tecniche e musicali dagli arpisti, purtroppo le melodie trascritte furono spesso “arrangiate” dallo stesso Bunting, un organista di formazione classica, che annotò per lo più solo le melodie e non gli accompagnamenti.

The oldest musical compositions that have come down to us were transcribed by the Irish bards in the late 1500s, but most of these music was lost, because they were handed down orally from master to pupil. Starting from the High Middle Ages, the harp is elected as a privileged instrument of the Bard and is called bardic harp to underline the union between the two.

The Irish bardic order is “extinguished” in the eighteenth century and immediately some philanthropist was able to organize meetings (competitions, dances, festivals) to transcribe the melodies and preserve for the future centuries a vivid testimony of the legacy of the old Bards .

Belfast Bardic Music Festival

The first of these meetings was held in Belfast in 1792 in July, when only a dozen harpists showed up, the youngest was 15 and the eldest, Denis Hempson, was 97.

On that occasion Hempson still played the old way, pinching the strings with his fingernails and placing the harp on his left shoulder – with his hands moving in reverse to the more modern technique.

Edward Bunting Heritage

Edward Bunting was commissioned to transcribe the songs performed by the harpists in the 4 days of the festival and his enthusiasm was such that he did not stop for all his life.So he published three musical collections, in 1797, 1809, and 1840.

Bunting collected a lot of historical, technical and musical information from the harpists, unfortunately the transcribed melodies were often “arranged” by the same Bunting, a classical training organist, who wrote down mostly only the melodies and not the accompaniments.

Scozia

Scozia

Ciclo Feniano

Ossian è un bardo leggendario dell’antica Scozia o Irlanda, paragonato ad Omero e a Shakespeare, grazie al presunto ritrovamento dei suoi poemi in Scozia. Le sue leggende si rincorrono in Irlanda, Isola di Man e Scozia, ma la sua popolarità crebbe solo nella metà del 1700 quando James MacPherson scrisse “I Canti di Ossian” affermando di aver ritrovato suoi manoscritti e frammenti nelle Highlands scozzesi, tra i quali un poema epico su Fingal, il padre, che disse di aver “semplicemente” tradotto, in realtà inventando di sana pianta: la moda ossianica divampò per tutta Europa dando vita al Romanticismo. continua

Gli studiosi identificano Ossian con l’Oisin (pronunciato Osciin) guerriero dei Fianna, che visse in Irlanda secondo alcuni nel VII secolo a.C. e secondo altri nel II o IV secolo, di cui si narrano molte leggende. Suo padre era Finn Mac Coll (Fionn Mac Cumhaill) il più famoso degli eroi irlandesi. Questi racconti mitologici dell’antica Irlanda vengono anche chiamati “Ciclo Ossianico” perchè si ritenne fossero stati in buona parte scritti da Ossian. Iniziano con l’ascesa di Fionn, il Biondo a capo dei Fianna e si concludono con la sua morte. continua

Carmina Gadelica: la musica bardica scozzese

Un’altra preziosa fonte ci arriva dal lavoro di ricerca compiuto dallo studioso scozzese nonchè Reverendo Alexander Carmichael (1832-1912) il quale girò in lungo e in largo le Highlands e le Isole parlando con le persone comuni affinchè cantassero le loro canzoni e raccontassero il proprio stile di vita. Così raccolse nel suo libro “Carmina Gadelica”, “inni, incantesimi e magie” della tradizione orale e li tradusse in inglese. [La Keltia editrice ha pubblicato il libro in italiano]

Ortha nan Gaidheal

Nel mondo contadino esistevano ancora tutta una serie di preghiere e invocazioni, spesso in forma di canzoni, che facevano parte del bagaglio culturale risalente al tempo dei Druidi, alla tradizione bardica sopravvissuta nella tradizione orale di un popolo.

Another precious source comes from the research work carried out by the Scottish scholar and Reverend Alexander Carmichael (1832-1912) who traveled far and wide to the Highlands and the Islands talking to folk people so that they would sing their songs and tell their lifestyle. Thus he had collected in his book “Carmina Gadelica” “hymns, spells and magic” from the oral tradition, translating them in English.

Ortha nan Gaidheal

In the peasant world still existed a whole series of prayers and invocations, often in the form of songs, (Ortha nan Gaidheal -the Songs of the Gaels) which were part of the cultural baggage dating back to the time of the Druids, to the bardic tradition that survived in the oral tradition of a people.

LA RINASCITA DELL’ARPA IN BRETAGNA

LA RINASCITA DELL’ARPA IN BRETAGNA

Una nuova tradizione, la rinascita dell’arpa celtica, riparte agli inizi del Novecento in un paese in cui l’arpa era scomparsa molto prima che nelle Isole Britanniche. Prende le mosse da Alan Stivell figlio di Jord Cochevelou, che negli anni cinquanta si mise a costruire un modello d’arpa più simile ai modelli medievali o tardo medievali conservati nei musei.

E così poco a poco l’arpa celtica ritorna ad essere un simbolo, un sogno mitico, una volontà di radicarsi nelle musiche popolari delle proprie nazioni o regioni, sia anche un luogo dello spirito, non necessariamente legato ad una dimensione geografica.

Nel 2002 esce un album tutto strumentale in cui Alan Stivell suona sei tipi diversi di arpa e che intitola Beyond Words (Al di là delle parole): con il suo stile personalissimo e la sua costante ricerca Stivell è considerato il massimo esponente dell’arpa celtica.

A new tradition, the revival of the Celtic harp, restarts at the beginning of the twentieth century in a country where the harp had disappeared much earlier than in the British Isles. It starts from Alan Stivell son of Jord Cochevelou, who in the fifties build a harp model more similar to medieval or late medieval models preserved in museums.

And so little by little the Celtic harp becomes again a symbol, a mythical dream, a desire to take its root in the popular music of one’s own nation or region, but also a place of the spirit, not necessarily tied to a geographical dimension.

In 2002 Alan Stivell released an instrumental album in which he plays six different types of harp, entitled Beyond Words: with his very personal style and his constant research Stivell is considered the greatest exponent of the Celtic harp .

![]() Telenn la Harpe Bretonne Alan Stivell & Jean-Noel Verdier

Telenn la Harpe Bretonne Alan Stivell & Jean-Noel Verdier

I TEMI della Musica bardica

Gli Eroi

Compito del bardo era descrivere le gesta degli eroi e tramandare il nome dei guerrieri ai posteri e in particolare dei suoi mecenati. Come per l’Achille omerico un guerriero andava incontro a piè veloce ad una breve vita purchè le sue imprese fossero cantate dai poeti!

Cara Terra

Un altro argomento prediletto era il canto della bellezza della terra natia o più in generale della vita nei boschi a cacciare il cervo e a nuotare nei ruscelli.. come i canti in gaelico scozzese provenienti dalle Highlands e sopravvissuti nei canti di lavoro della gente del popolo.

The Heros

The task of the bard was to describe the deeds of the heroes and to pass on the name of the warriors to posterity and in particular to its patrons. As for the Homeric Achilles, a warrior went to meet a quick way to a short life as long as his feats were sung by poets!

Loved Land

Another favorite topic was the song of the beauty of the homeland or more generally of life in the woods to hunt the deer and to swim in the streams .. like the Scottish Gaelic chants coming from the Highlands and survivors in the working songs of the people .

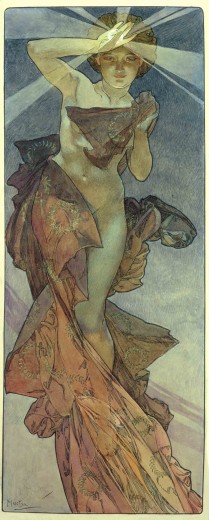

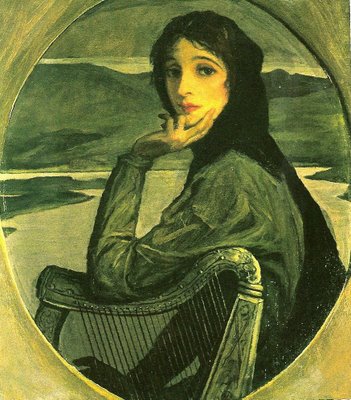

Aisling, la poesia bardica irlandese

Aisling (dall’irlandese) è un genere tipico della poesia bardica irlandese, che si sviluppò tra la fine del XVII e il XVIII secolo, dove il poeta incontra una donna dell’Altromondo che simboleggia l’Irlanda. L’incontro ha il carattere di una visione o di un sogno poco prima del farsi del giorno, in cui la fanciulla è di una bellezza mozzafiato ovvero sublime, paragonata alla più bella delle dee.

Talvolta però la donna è una povera vecchia (“An tSeanbhean Bhocht” la Sean-Bhean bhocht) ovvero la signora Katty Hualloghan – Cathleen o Kathleen Nì Houlihan-, padrona di quattro campi verdi (cioè le quattro province in cui è divisa per tradizione l’Irlanda).

La libertà

I dialoghi sono volutamente oscuri, all’epoca gli arpisti erano spesso perseguitati e banditi perchè incitavano alla ribellione: l’alba che sta per sorgere è una chiara allusione alla libertà che arriverà inesorabilmente dalla sconfitta del dominio inglese.

Il Futuro radioso

In genere questa “donna del cielo” [spéirbhean] si lamenta delle condizioni di vita del popolo irlandese e prevede un futuro radioso, in cui sarà libera dagli oppressori.

Questo risveglio della sua sorte è solitamente legato alla restaurazione della casa cattolica romana degli Stuart sul trono di Gran Bretagna e Irlanda.

La chiave politica è una lettura tipicamente irlandese di un genere sviluppato in Francia con il termine Reverdie, in cui il poeta incontra una dama soprannaturale, che simboleggia la natura rigogliosa e l’amore. In questo genere poetico si festeggia l’arrivo della bella stagione e lo sbocciare dell’amore.

The aisling (Irish for ‘dream’ / ‘vision’, pronounced [ˈaʃlʲəɲ], approximately /ˈæʃlɪŋ/ ASH-ling), or vision poem, is a Mythopoeic poetic genre that developed during the late 17th and 18th centuries in Irish language poetry

A typical genre of Irish bardic poetry is called in Gaelic Aisling, where the poet meets a woman from the Otherworld, who symbolizes Ireland. The meeting has the character of a vision or a dream just before the day, in which the girl is of breathtaking beauty or sublime, compared to the most beautiful of the goddesses.

Sometimes, however, the woman is a poor old woman (“An tSeanbhean Bhocht”) or Mrs Katty Hualloghan – Cathleen or Kathleen Nì Houlihan-, mistress of four green fields (i.e. the four provinces into which Ireland is traditionally divided).

Freedom!

The dialogues are deliberately obscure, in that time harpists were often persecuted and banned because they incited the rebellion: the dawn that is about to rise, is a clear allusion to the freedom that will come inexorably from the defeat of English domination.

A bright future

Generally this ‘heavenly woman’ -spéirbhean (pronounced [ˈsˠpʲeːɾʲvʲanˠ]-, complains about the living conditions of the Irish people and foresees a bright future, in which she will be free from the oppressors.

This frevival of her fortune is usually linked to the restoration of the Roman Catholic House of Stuart to the thrones of Great Britain and Ireland.

The political key is a typically Irish reading of a genre developed in France with the term Reverdie, in which the poet meets a supernatural lady, symbolizing luxuriant nature and love. In this poetic genre it’s celebrate the arrival of the beautiful season and the blossoming of love.

Slow airs

Le aisling song sono in genere delle slow air di una dolcezza mista a tristezza infinita e per lo più sono composte in gaelico irlandese, per rivendicare l’indipendenza culturale dall’inglese, e le proprie radici celtiche!

Molte aisling sono spesso ancora cantate come canzoni tradizionali di sean-nós.

The aisling songs are usually a slow airs of a sweetness mixed with infinite sadness and are mostly composed in Irish Gaelic, to claim cultural independence from English, and their Celtic roots!

Many aisling poems are often still sung as traditional sean-nós songs.

A-Z Musica Bardica (tradizionale)

Attenzione molti dei canti riportati risalgono alla tradizione bardica medievale per lo più solo per la melodia, essendo le versioni testuali riconducibili a riscritture più recenti; solo di pochissimi si sono conservati gli antichi testi (abbinati spesso a melodie di nuova composizione)

Pay attention: many of the songs reported go back to the Bardic medieval tradition mostly only for the melody, being the textual versions attributable to more recent rewrites,; only very few have preserved the ancient texts (often combined with melodies of new composition)

- AN CHÚILFHIONN – THE COOLIN’ (Maurice O’Dugan –Muiris Ua Duagain)

- AR EIREANN NI NEOSAINN CE HI

- AR HYD Y NOSASH GROVE (tradizione bardica gallese)

- BARD OF ARMAGH

- BEINN A’ CHEATHAICH (Nic Iain Fhinn)

- Berceuse de Gráinne pour Diarmait (Hughes de Courson)

- CALLÍN DEAS CRUÍTE NA MBÓ

- CARRICKFERGUS (Cathal “Buí” Mac Giolla Ghunna)

- Celtic Spell

- Cétemain, caín cucht (VII sec)

- Chuachag nan Craobh

- COISICH A RÙIN

- CRODH CHAILEINDANNY BOY (“Ruairi Dall” O Cathain )

- DUAN NA MUTHAIRN (Bear McCreary)

- DAWNING OF THE DAY (Thomas O’Connellan )

- EILEEN AROON ( Carol O’Daly –Cearbhall O Dálaigh)

- GIVE ME YOUR HAND/TABHAIR DOM DO LAMH (“Ruairi Dall” O Cathain )

- INVOCATION OF THE GRACES

- KATHARINE OGIE

- KISHMUL’S GALLEY

- MINSTREL BOY

- MNÁ NA HÉIREANN (Women of Ireland)

- MO GHILE MEAR ( Seán Clárach MacDomhnaill )

- ORAN FEAR GHLINNE-CUAICH

- OSSIAN’S LAMENT

- RÓISÍN DUBH

- SEATHAN AN-DIUGH NA MHARBHAN

- SI BHEAG, SI MHOR (Turlough O’Carolan)

- SMEÒRACH CHLANN DÒMHNAILL(John MacCodrum –Iain Mac Fhearchair)

- SOUTH WIND (Domnhall “Meirgeach” Mac ConMara)

- A Ghealaich

- TRUE THOMAS (Thomas di Ercildoune)

- TWA MAGICIANS

Poesia bardica contemporanea

I nuovi Bardi?

Posto che il bardo era un poeta-arpista del popolo celtico, nasce spontaneo domandarsi, chi sono oggi i nuovi bardi? Ovviamente il termine sarà riduttivo (rispetto al primigenio significato di druido-bardo), ma paradossalmente anche più esteso: bardo è il poeta che scrive nel linguaggio del popolo, il bardo è il poeta che scrive e canta per il popolo (qualunque sia lo strumento utilizzato); il bardo è anche l’arpista che suona l’arpa tradizionale (quella senza pedali) ispirandosi ai suoni della natura/anima e alle melodie della tradizione.

Bardic Music nowaday?

Given that the bard was a poet-harpist of the Celtic people, the question arises spontaneously, who are the new bards today? Obviously the term will be reductive (compared to the primeval meaning of druid-bard), but paradoxically even more extensive: bard is the poet who writes in the language of the people; bard is the poet who writes and sings for the people (whatever the instrument used); the bard is the harpist who plays the traditional harp (the one without pedals) inspiring by the sounds of nature/soul and traditional melodies.

Poesia bardica contemporanea (nuovo argomento 2024)

APPROFONIMENTO

Rimando a quanto da me scritto sull’Arpa bardica nel sito “Terre celtiche e Medioevo”

La peculiarità del suono dell’arpa è la naturalezza con cui si ottiene il suono, pizzicando le corde con i polpastrelli, senza mediazione di meccanismi esterni. La sua bellezza è proprio questa “fluidità” del suono che richiama il movimento dell’acqua; inoltre il suono è dinamico con possibilità di variare nel piano e nel forte sulle sue corde gravi.

I primi bardi suonavano l’antenata dell’arpa ossia la lyra, uno strumento diffuso presso la cultura greca ai tempi di Omero e anche nel Nord-Europa... [Cattia Salto]

Bellissimo e prezioso articolo, grazie. Vi segnalo un ulteriore eccezionale bardo contemporaneo dalle magiche note e atmosfere fatate https://arthuanrebis.jimdo.com/

Tratto principale dell’identificazione dei popoli celtici e l’appartenenza a una medesima famiglia linguistica, quella delle lingue celtiche . Tale famiglia e parte del piu ampio insieme indoeuropeo, dal quale si distacco nel III millennio a.C. Tre sono le principali ipotesi che precisano meglio il momento della separazione del celtico comune o protoceltico .