La rivolta durò una breve stagione dal maggio al settembre del 1798 e venne chiamata con il nome di “United Irishmen Rebellion” perché condotta da un gruppo politico denominato Society of United Irishmen, ovvero un gruppetto di intellettuali e di eminenti cittadini per lo più di confessione presbiteriana e anglicana (ma anche cattolici) che volevano riunire tutti gli Irlandesi (senza distinzione di fede) in una repubblica indipendente.

[english version]

The revolt lasted a short season from May to September 1798 and was called “United Irishmen Rebellion” because it was led by a political group called the Society of United Irishmen, a small group of intellectuals and eminent citizens mostly confessional Presbyterian and Anglican who wanted to bring together all the Irish (without distinction of faith) in an independent republic

L’unione fa la forza

L’associazione, fondata nel 1791a Belfast da un gruppo di nove presbiteriani capeggiati da Theobald Wolfe Tone, voleva riformare il Parlamento irlandese di Dublino (per ampliarne la base di rappresentatività) e perseguiva l’unione di tutti gli irlandesi a prescindere dalla loro osservanza religiosa e provenienza sociale affinchè la minoranza anglicana privilegiata concedesse piena uguaglianza politica ai presbiteriani e ai cattolici.

Fu un tentativo di creare l’alleanza tra anglicani liberali, presbiteriani e cattolici irlandesi che però non si recuperò più, in quanto i protestanti irlandesi finirono per identificarsi nel modello “british” mentre la successiva lotta per l’indipendenza della Repubblica d’Irlanda sarà combattuta prevalentemente dalla popolazione cattolica irlandese.

Da Belfast a Dublino

L’associazione da Belfast si ramificò fino a Dublino per operare tramite la diffusione delle idee illuministe su larga scala con opuscoli, giornali, fogli volanti, accompagnata anche da letture pubbliche, ma venne ben presto dichiarata fuori legge (1794) così operò in clandestinità, fino ad accrescere il numero dei sui affiliati allo scoppio della rivoluzione francese.

Lo sbarco dei Francesi

Gli eventi precipitarono quando Francia e Inghilterra entrarono in guerra nel 1793 e i francesi scelsero la baia di Bantry nella contea di Cork (era il 21 dicembre 1796) come sbarco della flotta d’invasione. Per circostanze non ancora chiarite la nave ammiraglia mancò all’appuntamento e le altre navi, a causa di una violenta tempesta, decisero di ritornare indietro.

La repressione inglese

La reazione inglese fu terribile: scoperto il complotto in cui gli United Irishmen avrebbero dovuto dare man forte alle operazioni militari francesi contro l’Inghilterra, si passò a una feroce repressione, basata su torture giornaliere di una popolazione inerme sospetta di essere in combutta con l’associazione clandestina. Alla ricerca di armi e di teste, si frustarono a sangue e torturarono brutalmente, irlandesi di tutte le confessioni religiose, spesso dei pacifici capi famiglia senza nessuna colpa, ma anche donne, allo scopo di estorcere delle confessioni. Molto probabilmente l’odio etnico si radicò allora segnando una profonda e insanabile rottura tra irlandesi e inglesi.

23 maggio 1798

Nonostante che i capi fossero stati quasi tutti arrestati, la ribellione scoppiò così come progettato in data 23 maggio 1798 e anche se la presa di Dublino fallì a causa della trappola fatta scattare dagli inglesi a conoscenza dei piani della rivolta, in molte contee nei dintorni di Dublino si ebbero aspri combattimenti con un temporaneo controllo da parte dei ribelli, di un vasto territorio a mezzaluna intorno a Dublino che comprendeva la contea di Meath, Kildare, Wicklow, Carlow e Wexford compresi anche vasti territori nell’Ulster orientale (nelle contee di Antrim e Down).

A metà agosto, quando i principali centri dell’insurrezione erano stati sconfitti, lo sbarco di un contingente francese a Kilcummin nella contea di Mayo, sostenuto dai ribelli locali, ha portato alla creazione dell’effimera “Repubblica del Connaught“, ma a settembre con la sconfitta nella battaglia di Ballinamuck nella contea di Longford si concludeva la breve stagione della speranza irlandese per l’indipendenza: l’atto d’unione del 1800 ha creato il Regno Unito di Gran Bretagna e Irlanda, con l’abolizione del Parlamento di Dublino.

The association, founded in Belfast in 1791 by a group of nine Presbyterians led by Theobald Wolfe Tone, wanted to reform the Irish Parliament in Dublin (to broaden its representational base) and pursued the union of all Irish people regardless of their observance religious and social origin, so that the privileged Anglican minority granted full political equality to Presbyterians and Catholics.

It was the first and last attempt to create an alliance between Liberal Anglicans, Presbyterians and Irish Catholics, while the subsequent struggle for the independence of the Republic of Ireland will be fought mainly by the Irish Catholic population, because the Irish Protestants identifying themselves in the “British” model.

The association from Belfast branched to Dublin to operate through the dissemination of large-scale Enlightenment ideas with pamphlets, newspapers, leaflets, accompanied by public readings, but was soon declared outlawed (1794) so they worked in hiding, up to increase the number of their affiliates to the outbreak of the French revolution.

The events precipitated when France and England entered the war in 1793 and the French chose Bantry Bay in the county of Cork (it was December 21, 1796) to landing their invasion fleet supporting Irish rebellion. For reasons not yet clear, the flagship missed the appointment and the other ships, due to a violent storm, decided to go back.

The English reaction was terrible: a ferocious repression, based on the daily torture of an unarmed population suspected of being in league with the clandestine association. In search of arms and heads, they whipped to death and brutally tortured, Irishmen of all religious confessions, often peaceful family leaders without any fault, but also women, in order to extract confessions. Most likely, ethnic hatred took root here, marking a deep and irremediable break between Irish and English people.

Despite the fact that the chiefs were almost all arrested, the rebellion broke out as planned on May 23, 1798, and even though the Dublin grasp failed because the British aware of the revolt plans, in many counties around Dublin there were fierce fighting with a temporary control by rebels in a vast crescent-shaped territory around Dublin which included the county of Meath, Kildare, Wicklow, Carlow and Wexford including large territories in eastern Ulster (in the counties of Antrim and Down).

In mid-August, when the main centers of the uprising were defeated, the landing of a French contingent at Kilcummin in Co. Mayo, supported by local rebels, led to the creation of the ephemeral “Republic of Connaught”, but in September with the defeat at the Battle of Ballinamuck in Co. Longford the short season of Irish hope for independence ended: the 1800 union act created the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, with the abolition of the Dublin Parliament .

La Ribellione a Wexford

Nella contea di

Wexford (Irlanda Sud-Est) i ribelli (mobilitati in grande numero) sconfissero i governativi a maggio, nella prima fase della rivolta.

Nel pomeriggio del 27 maggio (la domenica di Pentecoste) un migliaio di ribelli si erano uniti a Oulart Hill:erano male armati, alcuni con picche e armi da fuoco, ma la maggior parte con forconi e falcetti, eppure sconfissero la milizia e gli yeomen (1).

Il 29 maggio 5000 ribelli conquistarono la cittadina di Enniscorthy. Dopo pochi giorni l’esercito ribelle era arrivato a 15.000 uomini. Tra i capi dei ribelli Padre John Murphy parroco di Boolavogue un semplice prete di campagna che si unì alla rivota consigliando ai suoi parrocchiani “di morire coraggiosamente in battaglia piuttosto che essere massacrata nella propria casa“. Diventato il capo dei ribelli del sua paese, seppe condurre la gente comune, inesperta e equipaggiata alla meglio alle vittorie di Oulart Hill, The Harrow, Camolin, Ferns e Enniscorthy.

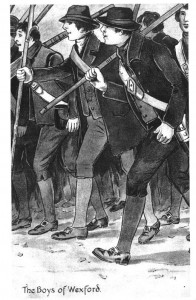

Gli insorti non avevano una divisa, ma indossavano per lo più abiti civili ed era consuetudine aggiungere al cappello una fascia bianca o verde con la scritta ” Liberty and Equality” oppure “Erin go Braugh”. L’armamentario poi era quanto mai raffazzonato, costituito per lo più dalle picche (ovvero una punta metallica montata su una lunga asta di legno). Quest’arma serviva a contrastare le cariche della cavalleria, ma era diventata obsoleta con il diffondersi dell’artiglieria e superata infine con l’introduzione della baionetta.

Fu a Wexford (abbandonata dagli Inglesi in fuga) che l’esercito sempre più numeroso dei ribelli si diede una struttura di comando: Bagenal Harvey, un ricco protestante e leader degli Irlandesi Uniti di Wexford, liberato dal carcere, assunse il ruolo di comandante generale (poco dopo sostituito da padre Philip Roche). L’esercito venne diviso in tre gruppi e al gruppo in cui era Padre Murphy venne dato l’ordine di prendere Gorey e Arlow. Ad Arlow però i ribelli furono sconfitti e ricevettero l’ordine dal nuovo comandante in capo padre Philip Roche di ripiegare a Vinegar Hill dove era stato montato il campo centrale dell’esercito.

Su quella collina il 21 giugno si infransero le speranze della repubblica di Wexford!

In the county of Wexford (south-east Ireland) the rebels (mobilized in large numbers) defeated the government in May, in the first phase of the uprising.

On the afternoon of May 27th (Pentecost Sunday) a thousand rebels had joined Oulart Hill: they were badly armed, some with spades and firearms, but most with pitchforks and sickles, yet they defeated the militia and the yeomen (1).

On the afternoon of May 27th (Pentecost Sunday) a thousand rebels had joined Oulart Hill: they were badly armed, some with spades and firearms, but most with pitchforks and sickles, yet they defeated the militia and the yeomen (1).

On May 29, 5000 rebels conquered the town of Enniscorthy. After a few days the rebel army had reached 15,000 men. Among the leaders of the rebels, Father John Murphy, parish priest of Boolavogue, a simple country priest who advising his parishioners “to die courageously in battle rather than being massacred in their own home”. He became the leader of the rebels of his country, was able to lead ordinary people, inexperienced and best equipped to the victories of Oulart Hill, The Harrow, Camolin, Ferns and Enniscorthy.

The insurgents did not have a uniform, but they wore mostly civilian clothes and it was customary to add a white or green band to the hat with the words “Liberty and Equality” or “Erin go Braugh”. The paraphernalia was then very botched, consisting mostly of spades (or a metal pike mounted on a long wooden pole). This weapon was used to counter the charges of cavalry, but it had become obsolete with the spread of artillery and finally overcome with the introduction of the bayonet.

It was in Wexford (abandoned by the British on the run) that the ever-increasing army of rebels gave a command structure: Bagenal Harvey, a wealthy Protestant and leader of the United States of Wexford, freed from prison, assumed the role of general commander (shortly afterwards replaced by father Philip Roche). The army was divided into three groups and the group of Father Murphy was given the order to take Gorey and Arlow. In Arlow, however, the rebels were defeated and received the order from the new commander in chief father Philip Roche to fall back to Vinegar Hill where the army’s central camp had been mounted.

On that hill on June 21, the hopes of the Wexford republic were broken!

LA BATTAGLIA DI VINEGAR HILL

Vinegar Hill si trova nelle vicinanze di Enniscorthy: i due eserciti erano quasi di pari forza, ma i ribelli erano male armati e men che meno addestrati. Anche la cittadina si difese strenuamente dai ripetuti attacchi della fanteria inglese (supportata da cannoni e cavalieri), ma pian piano i ribelli furono costretti a cedere il terreno; sulla collina di Vinegar i ribelli riuscirono infine a ritirarsi e a fuggire in un varco lasciato libero dell’incompleto accerchiamento dei governativi.

La città venne abbandonata e da allora i ribelli si dispersero in azioni di guerriglia e razzie che si trascinarono fino agli inizio dell’Ottocento. Ma il seme della ribellione riprende a germogliare nel cuore dei Feniani.

THE BATTLE OF VINEGAR HILL

Vinegar Hill is located near Enniscorthy: the two armies were almost equally strong, but the rebels were badly armed and less trained. The town was strenuously defended by repeated attacks of the British infantry (supported by cannons and knights), but slowly the rebels were forced to retire; on the hill of Vinegar the rebels finally managed to flee in a gap left free of the partial encirclement of the government troups.

The city was abandoned and since then the rebels dispersed in guerrilla actions and raids that dragged on until the beginning of the nineteenth century. But the seed of the rebellion resumes to sprout in the heart of the Fenians.

LINK& NOTE

Vinegar Hill, Enniscorthy, ‘who fears to speak of 98’ http://www.irelandinpicture.net/2010/03/vinegar-hill-enniscorthy-who-fears-to.html

(delle foto strepitose nel blog “Pictures of Ireland” da un irlandese che per lavoro deve viaggiare per l’Irlanda!)

[(amazing photos in the “Pictures of Ireland” blog from an Irishman who has to travel to Ireland for work!)]

http://kildarelocalhistory.ie/1798-rebellion/background-to-rebellion/united-irishmen/

http://multitext.ucc.ie/d/The_1798_Rebellion_in_Wexford

“Croppy” è il soprannome dato ai ribelli irlandesi del 1798; significa “taglio corto dei capelli” perché, secondo George Denis Zimmerman (in “Songs of Irish Rebellion 1780-1900” -1966 ) i ribelli volevano emulare gli antichi romani al tempo della Repubblica, così come facevano i coevi rivoluzionari francesi.

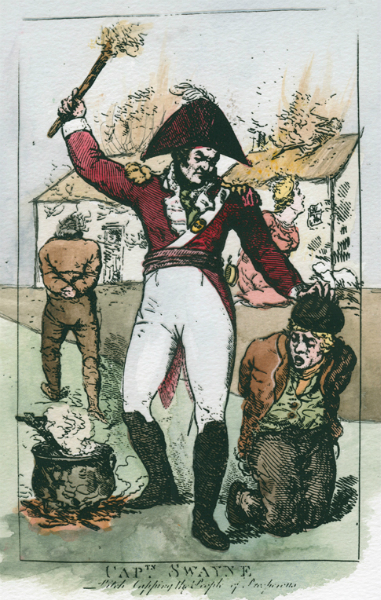

Una versione più prosaica vuole far derivare il soprannome dalla tortura inventata dagli inglesi per l’occasione, detta pitchcapping, i quali rasavano i capelli dei ribelli e ricoprivano il loro cranio con la pece bollente; era quindi inizialmente un termine dispregiativo coniato dagli inglesi, poi rivendicato con orgoglio dagli Irlandesi.

Il termine compare anche nella canzone popolare anti-repubblicana “Croppies lie down” che celebra la sconfitta dei ribelli, la preferita dall’Orange Order (gli anglicani reazionari).

“L’orzo che si muove nel vento” è diventato il simbolo dei ribelli irlandesi del 1798, pare che sulle fosse comuni dove venivano seppelliti i “croppy boys“, crescesse l’orzo, germogliato dalle razioni di cibo che si portavano in tasca; così lo spirito del nazionalismo irlandese non poteva essere distrutto e tornava a rinasce.

1) yeoman, yeoa: originariamente il nome dato ai coltivatori diretti inglesi del XVII secolo che fornirono soldati per lo più nel corpo a cavallo dell’esercito inglese. Nel 1790 vennero formati i reggimenti Yeomen in risposta alla minaccia rappresentata dalla Francia in seguito alla rivoluzione francese. Era una forza riservista e volontaria, composta principalmente da piccoli agricoltori e proprietari terrieri che erano fedeli alla Corona. Essi si trovavano in tutta la Gran Bretagna, ma fu in Irlanda, che vennero coinvolti come prima linea di difesa contro i ribelli. Qui indica una unità militare britannica impiegata nella Battaglia di Harrow del 26 maggio 1798 a Wexford, la Camolin Cavalry.

Occorre osservare ad onor del vero che le yeomanry nel XVIII secolo erano composte anche da volontari irlandesi, per lo più orangisti ovvero appartenenti all’Orange Order

“Croppy” is the nickname given to the Irish rebels of 1798; means “short hair cut” because, according to George Denis Zimmerman (in “Songs of Irish Rebellion 1780-1900” -1966) the rebels wanted to emulate the ancient Romans at the time of the Republic, as did the contemporary French revolutionaries.

A more prosaic version wants to derive the nickname from the torture invented by the British for the occasion, called pitchcapping, which shaved the hair of the rebels and covered their skull with some boiling pitch; it was therefore initially a derogatory term coined by the British, then claimed with pride by the Irish.

The term also appears in the popular anti-republican folk song “Croppies lie down” celebrating the defeat of the rebels, the favorite of the Orange Order (the reactionary Anglicans).

“The barley that moves in the wind” has become the symbol of the Irish rebels of 1798, it seems that on the mass graves where the “croppy boys” were buried, barley grew, sprouted from the food rations that were carried in their pockets; thus the spirit of Irish nationalism could not be destroyed and returned to rebirth.

yeoman, yeoa: originally the name given to the British direct cultivators of the seventeenth century who provided soldiers mostly in the British army body riding. In 1790 the Yeomen regiments were formed in response to the threat posed by France following the French revolution. It was a reservist and voluntary force, composed mainly of small farmers and landowners who were loyal to the Crown. They were in all of Britain, but it was in Ireland that they were involved as the first line of defense against the rebels. Here it indicates a British military unit employed in the Battle of Harrow on May 26, 1798 in Wexford, the Camolin Cavalry.

It should be noted to be true that the eighteenth-century Yeomanry were also composed of Irish volunteers, mostly Orangemen or members of the Orange Order

ARCHIVIO CANTI (Archive)

(The) Bantry girl’s lament

BOOLAVOGUE

BOYS OF MULLAGHBAWN

CROPPY BOY

KELLY OF KILLANNE

MINSTREL BOY

NELL FLAHERTY’S DRAKE

RISING OF THE MOON

WEARING OF THE GREEN

WIND THAT SHAKES THE BARLEY