WAULKING THE TWEED si dice di una particolare tecnica di manipolazione dei panni di tweed, secondo la tradizione artigianale messa a punto dalle donne scozzesi. Il tweed è un tessuto di lana originario dalla Scozia: caldo, resistente e pressoché indistruttibile, utilizzato dai pescatori e pastori scozzesi per tenersi più al caldo in un clima così freddo e ventoso, diventato solo nel 900 sinonimo di “british style” e di eleganza maschile.

L’ANTICA LAVORAZIONE DEL TWEED

I tessuti di tipo twill ovvero il tweed, detti anche diagonali, secondo alcuni archeologi erano molto comuni, in Europa, nell’età del ferro.

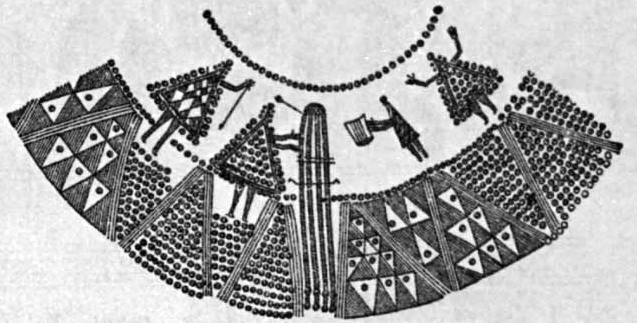

In questa illustrazione, tratta dall’Urna ritrovata a Oedenburg in Ungheria appartenente alla cultura celtica di Hallstatt e risalente alla tarda età del bronzo, vediamo raffigurato un telaio preparato per la lavorazione in diagonale (a saia)

English translation

The Scottish women have developed a particular technique for the twisting of the tweed, that woolen fabric from Scotland, warm, resistant and almost indestructible, used by fishermen and shepherds to keep warmer in a climate so cold and windy. The tweed is become only in the twentieth century synonymous with “british style” and elegance male.

Twill-type fabrics or tweeds, also called diagonals, according to some archaeologists were very common, in Europe, in the Iron Age.

In this illustration taken from the Urna found in Oedenburg in Hungary belonging to the Celtic culture of Hallstatt and dating back to the late Bronze Age, we see depicted a frame prepared for weaving

LA TECNICA PER L’INFELTRIMENTO DELLA LANA

Il tessuto ottenuto dal caratteristico intreccio a spina veniva poi sottoposto a follatura, una tecnica già nota agli antichi greci e messa a punto dalle donne delle Isole Ebridi, tecnica che restringe la lana e migliora le prestazioni del tessuto. La pezza di stoffa lunga una settantina di metri era cucita alle estremità, quindi si iniziava la lavorazione (waulking the tweed) che durava anche una giornata intera (un tempo si usavano .. i piedi)

L’attività si poteva svolgere all’aria aperta ma più spesso in un capanno apposito, le donne si sedevano lungo due file opposte, la schiena contro il muro.. ecco come descrive la scena Diana Gabaldon nel romanzo storico “Il ritorno” -serie Outlander- capitolo 11 )

“..mentre battevano i piedi contro il lungo serpente di lana bagnata per ricavare il compatto tessuto infeltrito che proteggeva chi lo indossava dalla nebbia delle Highlands e persino dalla lieve pioggia, tenendolo al riparo dal freddo. Di tanto in tento una delle donne si alzava e usciva fuori e prendere il calderone di urina fumante dal fuoco. Con le gonne sollevate, lo piazzava poi al centro del capanno e inzuppava la stoffa con il suo contenuto, mentre i fumi esalavano caldi e soffocanti dalla lana bagnata, e le altre donne tiravano indietro i piedi per evitare gli spruzzi e facevano battute volgari. “Il piscio bollente fissa in fretta la tinta” mi aveva spiegato una delle donne .. a parte l’odore, il capanno era un posto caldo e confortevole, dove le donne di Lallybroch ridevano e scherzavano tra i rotoli di tessuto e cantavano insieme durante il lavoro, battendo ritmicamente le mani sul tavolo affondando i piedi sul tessuto fumante mentre se ne stavano sedute a terra, schiena contro schiena con la compagna”

WOOL FELTING TECHNIQUE

English translation

The fabric was subjected to fulling, a technique already known to the ancient Greeks and developed by the women of the Hebrides, a technique that tighten the wool and improves the performance of the fabric. The piece of cloth about seventy feet long was sewn at the ends, then they started the processing for a day long (once using .. the feet)

The activity could be carried out in the open air but more often in a special shed, the women sat along two opposite rows, their backs against the wall.

“Hot piss sets the dye fast,” one of the women had explained to me as I blinked, eyes watering, on my first entrance to the shed. The other women had watched at first, to see if I would shrink back from the work, but wool-waulking was no great shock, after the things I had seen and done in France, both in the war of 1944 and the hospital of 1744. Time makes very little difference to the basic realities of life. And smell aside, the waulking shed was a warm, cozy place, where the women of Lallybroch visited and joked between bolts of cloth, and sang together in the working, hands moving rhythmically across a table, or bare feet sinking deep into the steaming fabric as we sat on the floor, thrusting against a partner thrusting back.”

(From DRAGONFLY IN AMBER, Chapter 34, “The Postman Always Rings Twice”. Copyright© 1992 by Diana Gabaldon.)

OUTLANDER TV, season I: “Rent”

In Outlander TV serie this glimpse of life in a scottish village of eighteenth-century, is developed in the Dougal Mackenzie’s journey, as he collects rents from the tenants of Castel Leoch. Claire goes on the road with Dougal, and almost by chance, she hears some voices and sees the women as they are waulking the tweeds.

Outlander I, episode 5: Mo Nighean Donn

BAN DHUAN, la donna canzone

Le donne disposte tutte intorno dovevano sempre essere di numero pari con la donna-canzone (ban dhuan) messa a volte a capotavola, è lei a iniziare il canto per dare il ritmo al lavoro; il movimento della battitura consisteva in 4 tempi: prima si sbatteva il tessuto sul tavolo davanti a sé, poi si sbatteva verso il centro del tavolo, quindi si riportava alla posizione iniziale e infine lo si passava alla donna successiva (in senso orario). In genere ci volevano almeno sei canzoni perché si iniziasse a vedere il restringimento della pezza di stoffa, e ancora altre tre prima che il lavoro fosse finito. Allora si scuciva la cucitura e si avvolgeva la stoffa su di un rullo. La giornata si concludeva con una specie di festino dopo che le donne si erano ripulite un po’ e rinfrescate: si mangiava, beveva e ballava (festa alla quale finalmente si univano gli uomini del paese).

Negli anni 40-50 con il tramonto della lavorazione artigianale (in particolare dell’Harris Tweed) le canzoni di lavoro sono diventate occasione di session dimostrative o sono passate nei repertori di alcuni gruppi di musica celtica con l’inserimento di parti strumentali e voci maschili.

Cloth were “mistreated” by a group of women sitting around a table with 4 beat: first, the fabric is banged on the table in front of you, then slammed towards the center of the table, then returned to the initial position and then is passed to the next woman (clockwise). To count the time and make the work less monotonous the women sang some songs, there was the ban dhuan (or the song-woman) that directed the song, while the others followed her in the refrain. After some songs the fabric was softer, thicker, and more tightly woven.

In general, it took at least six songs to start seeing the narrowing of the cloth, and three more before the work was finished. Then the seam was peeled and the fabric was rolled up on a roll. The day ended with a kind of party after the women had cleaned up a little and freshened up: we ate, drank and danced (a party that finally joined the men of the village). In the years 40-50 with the sunset of the craftsmanship (in particular of the Harris Tweed) these work songs have become occasions for demonstrative sessions or have passed into the repertoires of some groups of Celtic music with the insertion of instrumental parts and male voices .

WAULKING SONGS

L’origine del nome “waulking” è incerta perdendosi l’etimologia ai tempi del tardo Medioevo sempre comunque associata con la lavorazione del tweed. In gaelico si dice luadh e i canti associati erano detti orain luaidh. Alcuni studiosi ritengono che la forma del canto derivi dai canti norreni (lo stesso stile responsoriale si trova nei canti delle isole Faeroe). La tradizione si è tramandata anche nei luoghi di emigrazione, così nella Nuova Scozia questi canti si chiamano milling songs.

Una waulking song può superare i 10 minuti di durata, e trova riscontro nella tipicità della lavorazione: all’inizio le pezze bagnate risultano pesanti e più difficili da manipolare (anticamente si usavano i piedi) da qui le melodie lente, associate a lamenti, mentre il tono si fa più vivace e quasi gioioso in altre melodie che sono quelle cantate verso la fine della lavorazione. Il tempo della lavorazione non era misurato in minuti ma in canzoni. Per ogni pezzo di stoffa ci volevano almeno 4 o 5 orain luaidh e a volte si arrivava fino a 9.

Gli Scozzesi erano anche molto superstiziosi: una canzone non doveva essere cantata più di una volta per ogni singolo pezzo di tweed, il numero delle donne implicate doveva essere sempre pari e il verso della lavorazione doveva essere orario. Agli uomini era talvolta permesso di assistere alla lavorazione e anche di cantare, ma non potevano prendervi parte.

The origin of the name “waulking” is uncertain, losing the etymology at the time of the late Middle Ages, always associated with tweed processing. In Gaelic it is called luadh (pronounced “loo-ugh”) and the associated chants were called orain luaidh (pronounced “or-ine loo-ie”). Some scholars believe that the shape of the song derives from the Norse songs (the same responsorial style is found in the songs of the Faeroe islands). The tradition has also been handed down in places of emigration, so in Nova Scotia these songs are called milling songs.

A waulking song can exceed 10 minutes in duration, and is reflected in the typical processing: at the beginning wet patches are heavy and more difficult to manipulate (in ancient times women used their feet) hence the slow melodies, associated with moans, while the tone becomes more lively and almost joyous in other melodies that are those sung towards the end of the work.

Processing time was not measured in minutes but in songs. For each piece of cloth it took at least 4 or 5 hours or luaidh and sometimes it was up to 9.

The Scotsmen were also very superstitious: a song was not to be sung more than once for every single piece of tweed, the number of women involved had to be always equal and the verse of the work had to be clockwise. Men were sometimes allowed to watch the work and even sing, but could not take part.

Per non annoiarsi e per alleggerire la fatica del lavoro, le donne cantavano utilizzando anche le canzoni come “conta tempo”: la ban dhuan (ovvero la donna-canzone) intonava la strofa e il resto delle altre donne la seguivano nel ritornello; mentre la strofa era in genere breve, di uno o due versi il ritornello era spesso lungo con almeno 4-5 versi con abbondante uso di “vocables” ovvero suoni sillabici senza senso . Del resto anche tutta la canzone non aveva un vero e proprio significato, essendo le parole scelte principalmente per mantenere costante il ritmo della lavorazione tuttavia la ban dhuan più abile riusciva a metterci i gossip del momento.

Ovviamente si finì per codificare le canzoni in una sorta di versione tramandata, anche se di volta in volta i versi delle strofe finivano per variare a piacere di chi cantava. Queste canzoni ci narrano così vicende storiche del XV-XVI secolo, oppure descrivono attività e usanze molto antiche. Spesso i versi delle strofe venivano riciclati da una canzone all’altra, ma il ritornello, invece, per quanto senza senso, è sempre diverso, forse perché è la parte corale del canto che in qualche modo lo connota rispetto agli altri. Caratteristico infine è il ritmo ben scandito, per il rumore della battitura sul legno della stoffa e con la ripetizione a catena degli stessi quattro movimenti si sviluppa un effetto ipnotico.

In order not to get bored and to ease the fatigue of work, the women sang also using the songs as “time counters”: the ban dhuan (or the woman-song) sang the verse and the rest of the other women followed her in the refrain; while the verse was usually short, of one or two lines, the refrain was often long with at least 4-5 lines with an abundant use of “vocables” or meaningless syllabic sounds. After all, even the whole song did not have a real meaning, being the words chosen mainly to keep the pace of the work constant, however the most skilful ban dhu was able to put the gossip of the moment.

In a second time the songs were classificated in a sort of handed down version, even if from time to time the verses varying to the pleasure of those who sang. These songs tell us about historical events of the XV-XVI century, or describe very ancient activities and customs. Often the lyrics were recycled from one song to another, but the refrain, however meaningless, is always different, perhaps because it is the choral part of the song that somehow connotes it compared to the others.

Finally, the rhythm is well marked, due to the noise of the beating on the wood of the fabric and with the repetition of the same four movements a hypnotic effect is developed