Lord Randal è una ballata tradizionale che inaugura un genere narrativo, in molteplici varianti detto “il testamento dell’avvelenato”.

Lord Randal is a folk ballad that inaugurates a narrative genre, collected in multiple variations called “The will of the poisoned man“.

PAGINA QUADRO

VERSIONI SCOZZESI

Lord Randal (Child # 12) -Scottish version

Ciod è a ghaoil a tha ort – scottis gaelic version

Lord Ronald, my Son (Robert Burns)

Croodin doo (nursery rhyme)

VERSIONI IRLANDESI

Henry my Son (Irish version)

Amhrán na hEascainne (gaelic irish version)

ALTRE VERSIONI

The Wild, wild Berry (english version from Shropshire)

Billy Boy (sea shanty)

“Il testamento dell’avvelenato” (Italian version)

Jimmy Randal (John Jacob Niles)

La ballata raccolta dal professor Child al numero 12 è ampiamente diffusa presso la tradizione popolare e si conoscono numerosissime varianti testuali abbinate ad altrettante numerose melodie.

E’ la storia di un figlio morente, perchè è stato avvelenato, che ritorna dalla madre per coricarsi a letto e fare testamento.

Il retroscena (conosciuto dal pubblico del tempo e perciò taciuto) è quello dell’incontro con l’amante gelosa o una fata che lo avvelena perchè respinta dal giovane in procinto di sposarsi con un’altra. (vedi Lord Olaf).

Con tutta probabilità Lord Randal ha origini italiane, passa per la Germania – Svezia e poi si diffonde nelle isole britanniche fino a sbarcare in America.

Com’è noto ai più, Bob Dylan ha trasformato la ballata nella folksong americana d’autore “A Hard Rain’s a-gonna Fall” durante il “Folk Revival” degli anni 60-70. Dylan ha mantenuto la stessa metrica e il messaggio, pur sviluppando un argomento diverso. La sua è infatti una canzone contro la guerra.

Riccardo Venturi scrive nella sua trattazione sulle Childs Ballads: “Questa ballata può avere avuto origine molto lontano dalle brughiere e dai lochs, e molto vicino a casa nostra. Il veleno, infatti, è un’arma assai strana nelle fiere ballate britanniche, dove ci si ammazza a colpi di spada; è un mezzo subdolo, ‘femminile’ di uccidere, e non a caso è stato sempre considerato, a livello popolare, proprio degli italiani.”

E prosegue “Esiste comunque un’altra ipotesi sull’origine della ballata, che la vorrebbe far risalire alle vicende di Ranulf, conte di Chester* (menzionate dal contadino Sloth nel ‘Piers Plowmanì di William Langland assieme alle ‘Rhymes of Robin Hood’). Alcune versioni mancano del testamento del cacciatore moribondo, ma i lasciti sono dei più svariati.”

(da “Fatti e Fattacci” in Ballate anglo-scozzesi)

[*Randal (Ranulph) III, sesto conte di Chester (1170–1232 cf)]

[English version]

The ballad collected by the professor Child at number 12 is widespread in popular tradition and there are many textual variations combined with as many melodies.

It’s the story of a dying son, because he has been poisoned, who returns to his mother to die in his bed and make a will.

The background (known to the public at the time) is that of the meeting with the jealous lover or a fairy: she poisons him because he is about to marry a new bride.

(see developments in Lord Olaf).

In all likelihood the ballad starts from Italy, passes through Germany to get to Sweden and then spread to the British Isles (Lord Randal) until it lands in America.

During the “Folk Revival” of the 1960s and 1970s Bob Dylan has transformed the traditional Scottish ballad “Lord Randal” into the American folk song “A Hard Rain’s a-skirt Fall“.

Riccardo Venturi noted “This ballad may have originated very far from the moors and lochs, and very close to our home [Italy]. The poison, in fact, is a very strange weapon in the fierce ballads of Britain, where they kill themselves with sword, it is a subtle, ‘feminine’ means of killing, and it is not by chance that it has always been considered, on a popular level, a really Italian thing. However, there is another hypothesis on the origin of the ballad, which would like to trace back the story to Ranulf, Count of Chester (mentioned by the farmer Sloth in ‘Piers Plowmanì by William Langland together with the’ Rhymes of Robin Hood ‘). Some versions lack the will of the moribund hunter, but the legacies are of the most varied.“

SCOTTISH VERSION (Child # 12)

[LA VERSIONE SCOZZESE]

| Lord Randal è da considerarsi strettamente connessa con il tema della Morte occultata ovvero dell’eroe morente che torna dalla caccia e che fa testamento (vedi Lord Olaf). Così Giordano Dall’Armellina scrive nel suo libro “Ballate Europee da Boccaccio a Bob Dylan”:“il nostro eroe, per dimostrare di essere degno di passare nel mondo degli adulti e di diventare un “vero uomo”, sfida il tabù e va a cacciare proprio nel greenwood. Tuttavia non riesce a prendere niente e, o perché affamato o più probabilmente perché sotto incantesimo, accetterà le anguille fritte che lui crede gli siano date dalla sua innamorata. Da un punto di vista razionale sarebbe stata una storia assurda. Che ci fa l’innamorata di Lord Randal nel greenwood con una padella e delle anguille? È presumibile che la donna che l’eroe incontra sia la morte nei panni di una fata. Tradotto in termini psicanalitici la fata, prendendo le sembianze della sua innamorata, diventa una proiezione dell’inconscio dell’eroe. Lei lo punisce non solo per non aver superato la prova, ma anche per aver infranto il tabù. Nello stesso tempo anche la sua dama lo punisce poiché ha dimostrato di non essere in grado di prendersi cura di lei. Anzi, è lei che lo nutre e lo umilia offrendogli il simbolo della sua mancata virilità. Prima di lui moriranno i falchi e i cani, gli stessi animali che accompagnavano Oluf in alcune versioni scandinave della morte occultata, ugualmente colpevoli per non essere stati in grado di aiutarlo.“ | Lord Randal is to be considered strictly connected with the theme of “the Concealed Death” or the dying hero who returns from hunting and makes a will (Lord Olaf ). So Giordano Dall’Armellina writes in his book “European Ballads from Boccaccio to Bob Dylan”: “our hero, to prove to be worthy to pass into the world of adults and become a” real man “, challenges the taboo and goes to hunt right in the greenwood, but he cannot catch anything; or because he is hungry or more likely he is under a spell, he will accept the fried eels that he believes are given to him by his true-love.From a rational point of view it would have been an absurd story: what is she doing in the greenwood with a pan? It is likely that the woman the hero encounters is death in the cloak of a fairy. If we want to translate the tale from a psychoanalytic point of view, we can assume that the fairy, by looking like his true-love, becomes a projection of the hero’s unconscious. Lord Randal is punished for two different reasons: he has not overcome the trial through which he would have entered the world of the adults, and he has broken a taboo, while at the same time his lady punishes him because he has shown not being able to take care of her. On the contrary it is her who feeds him, and humiliates him by offering him the symbol of his missed manhood. Before him, the hawks and the dogs will die, the same animals that accompanied Oluf in some Scandinavian versions of the Concealed death, equally guilty for not being able to help him. “ |

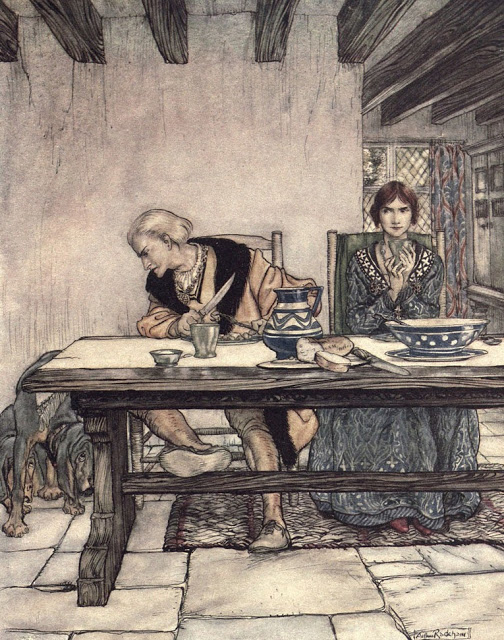

L’illustrazione di Arthur Rackham ritrae Lord Randal mentre è a tavola a mangiare le anguille con al fianco i suoi cani (che aspettano per gli avanzi o che hanno appena mangiato il boccone avvelenato); accanto una dama dallo sguardo perfido, che si presume sia la moglie, lo osserva furtivamente. L’illustratore così risolve l’incongruenza di un bacchetto con anguille fritte in padella nel folto del bosco che il figlio dice di aver mangiato poco prima di arrivare a casa della madre. Nei tipici salti temporali delle ballate infatti il figlio potrebbe benissimo essere andato a caccia nel bosco poi essere tornato alla sua dimora e aver mangiato con la moglie, poi essere andato alla casa della madre per fare testamento. Razionalizzando così la ballata la si riduce ovviamente ad una semplice storia di avvelenamento per vendetta coniugale.

The illustration by Arthur Rackham portrays Lord Randal while at the table eating the eels with some dogs alongside him (waiting for leftovers or having just eaten the poisoned morsel); next to a lady with a treacherous look, who is supposed to be his wife, looks at him stealthily.

The illustrator thus resolves the incongruity of a banquet with fried eel in pan into the greenwood, that the son says he ate shortly before arriving at his mother’s house. In the typical temporal jumps of ballads in fact the son could very well have gone hunting in the woods, then being returned to his home and having eaten with his wife, then being gone to his mother’s house to make a will. In this way, rationalizing the ballad it is a simple history of conjugal revenge poisoning.

she is performing Lord Randal with great talent

[intensa e lacerante interpretazione della giovane cantautrice]

I

“O where ha you been,

Lord Randal (Lord Donald), my son?

And where ha you been,

my handsome (bonnie) young man?”

“I ha been at the greenwood (1);

mother, mak my bed soon,

For I’m wearied wi hunting,

and fain wad lie doon. “

II

“An wha met ye there (2)?

And wha met ye there?”

“O I met wi my true-love;”

III

“And what did she give you (3)?

And wha did she give you?”

“Eels fried in a pan; mother”

IV

“And what gat your leavins?

And wha gat your leavins?”

“My hawks and my hounds”

V

“And what becam of them?

And what becam of them?”

“They stretched their legs out and died”

VI

“O I fear you are poisoned (4)!

I fear you are poisoned!”

“O yes, I am poisoned

For I’m sick at the heart,

and fain wad lie down.”(5)

VII

“What d’ye leave to your mother?

What d’ye leave to your mother?”

“Four and twenty milk kye”

VIII

“What d’ye leave to your sister?

What d’ye leave to your sister?”

“My gold and my silver”

IX

“What d’ye leave to your brother?

What d’ye leave to your brother?”

“My houses and my lands”

X

“What d’ye leave to your true-love (6)?

What d’ye leave to your true-love?”

“I leave her hell and fire”

NOTE

1) the greenwood is not just a common forest, but a sacred one the entrance to Otherword.

Dall’Armellina notes “It was the thickest part of the forest where the Celts believed there was the entrance to the world of the dead and to Fairyland. That entrance could be identified with a hollow trunk, a hole in the ground, a well and was defended and protected by fairies and elves.

On Halloween night the spirits of the dead used to come out of the greenwood to pay a visit to the living ones. The people were afraid of going to the greenwood and if they could, they avoided it.

I remember Robin Hood also hiding in the greenwood and that the soldiers of Nottingham’s sheriff, dared not come in for fear of the fairies and the spirits of the dead. The stories about Robin Hood, all deriving from ballads, are not by chance called The Greenwood Stories.

In any case if they ventured to pass by it, they would not speak in a loud voice so as not to disturb the spirits of the dead, they would not damage nature and above all, they would not hunt. According to local beliefs, they were taboos that, if broken, could cause death”

2) Emily Smith version

Wha did ye meet in the green woods

I met wi my sweethairt

3) or

What did ye hae for your dinner?

I had eels boiled in bree

4) In Celtic tradition, fairy food is magical with often hallucinogenic powers; those who taste it will not be able to eat other food, dying of hunger (did anorexics eat fairy food?)

5) variation of the refrain [variazione del ritornello]

6) Emily Smith

What will ye leave tae your sweethairt

A noose in yon high tree

I

“O dove sei stato,

Lord Randal, figlio mio?

O dove sei stato,

mio bel giovanotto?”

“Nella foresta,

mamma; presto, fammi il letto,

Ché son stanco della caccia

e mi voglio sdraiare.”

II

“E chi hai incontrato?

E chi hai incontrato?”

“La mia innamorata”

III

“E che cosa ti ha dato?

E che cosa ti ha dato?”

“Anguille fritte in padella”

IV

“E a chi hai dato gli avanzi

E a chi hai dato gli avanzi?”

“Ai falconi ed ai can”

V

“E cosa ne è stato ?

E cosa ne è stato ?”

“Han stirato le zampe e son morti”

VI

“Ho paura che tu sia avvelenato!

Oh, che tu sia avvelenato!”

“”Sì che m’hanno avvelenato

Ché il mio cuore è malato

e mi voglio sdraiare”

VII

“”E che lasci a tua madre?

Che lasci a tua madre?”

“Ventiquattro mucche”

VIII

“E che lasci a tua sorella?

Che lasci a tua sorella?”

“Il mio oro e l’argento”

IX

“E che lasci a tuo fratello?

Che lasci a tuo fratello?”

“Le mie case e la terra”

X

“E che lascia alla tua innamorata?

che lascia alla tua innamorata?”

“Il fuoco infernale”

NOTE

traduzione italiana di Riccardo Venturi (da “Fatti e Fattacci” in Ballate angloscozzesi) note a cura di Cattia Salto

1) il greenwood non è solo la foresta oscura, ma è il bosco sacro, la parte più nascosta che cela l’ingresso all’Altromondo celtico. Così racconta Dall’Armellina “Il greenwood era la parte più nascosta e fitta del bosco dove i celti credevano vi fosse l’ingresso del mondo dei morti e della terra delle fate e degli elfi (Fairyland). Tale ingresso, che poteva essere identificato in un tronco d’albero cavo, in una buca nel terreno, in un pozzo, era difeso e protetto dalle fate e dagli elfi. Nella notte di Halloween gli spiriti dei morti uscivano da questi antri naturali con le fate e gli elfi per far visita ai vivi. La gente temeva queste creature soprannaturali e se poteva evitava di inoltrarsi nel greenwood. Ricordo che anche Robin Hood si nascondeva nel greenwood e che i soldati dello sceriffo di Nottingham non osavano entrarci per paura delle fate e degli spiriti dei morti. I racconti riguardanti Robin Hood, tutti derivanti da ballate, non a caso si chiamano The greenwood stories.

In ogni caso, se vi si fossero avventurati, sapevano che non avrebbero potuto parlare ad alta voce, danneggiare il bosco, né tanto meno cacciare. Secondo le credenze locali erano dei tabù che, se infranti, avrebbero potuto causare la morte.”

2) Emily Smith

Wha did ye meet in the green woods

I met wi my sweethairt

3) oppure

What did ye hae for your dinner?

I had eels boiled in bree

4) Nella tradizione celtica il cibo delle fate è magico con poteri spesso allucinogeni; coloro che lo assaggiano non potranno mangiare altro cibo terrestre e finiscono per morire di fame (gli anoressici hanno mangiato cibo fatato?)

5) variazione del ritornello

6) Emily Smith

What will ye leave tae your sweethairt

A noose in yon high tree

LINK

Giordano Dall’Armellina: “Ballate Europee da Boccaccio a Bob Dylan”.

http://bluegrassmessengers.com/english-and-other-versions–12-lord-randal.aspx

http://71.174.62.16/Demo/LongerHarvest?Text=ChildRef_12

http://www.nspeak.com/allende/comenius/bamepec/multimedia/saggio2.htm

http://www.joe-offer.com/folkinfo/songs/37.html

http://www.joe-offer.com/folkinfo/songs/107.html

http://mainlynorfolk.info/martin.carthy/songs/lordrandall.html

http://www.macsuibhne.com/amhran/teacs/181.htm

http://chester.shoutwiki.com/wiki/Ranulf_de_Blondeville

Anche i Kornog nel loro quarto disco, registrato nel febbraio 1987, incisero la loro versione scozzese di “Lord Randall”, che porta il titolo di “Ma wee wee croodin doo”. L’avevano presentata in pubblico nel loro giro di concerti americani appena concluso (che qui, fortunatamente, vediamo documentata) :

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i6LMOWlR9T4

Il gruppo formato da Jamie McMenemy (bouzouki) che aveva lasciato la Battlefield Band per stabilirsi in Bretagna dopo avervi incontrato il chitarrista Soig Siberil e il violinista Christian Lemaitre, fu presto completato dal virtuoso suonatore autodidatta di flauto traverso in legno Jean-Michel Veillon (il primo a integrare questo strumento nei numerosi gruppi a cui ha partecipato) . Nel 1986 l’abbandono di Siberil portò alla sostituzione con Gilles Le Bigot ed è questa la formazione sia del tour che della registrazione di cui sopra.

Bonnie Wee Croodlin Doo

Whare hae ye been a’ the day,

My little wee croodlin doo?

Oh, I’ve been at my grandmother’s;

Mak’ my bed, mammie, noo!

What gat ye at your grandmother’s,

My little wee croodlin doo?

I got a bonnie wee fishie;

Mak’ my bed, mammie, noo!

Oh, whare did she catch the fishie,

My bonnie wee croodlin doo?

She catched it in the gutter hole;

Mak’ my bed, mammie, noo!

And what did you do wi’ the banes o’t,

My bonnie wee croodlin doo?

I gied them to my little dog;

Mak’ my bed, mammie, noo!

And what did the little doggie do,

My bonnie wee croodlin doo?

He shot out his head and feet, and dee’d,

As I do, mammie, noo!

Where hae ye been a’ the day,

My bonny wee croodin doo?

O I hae been at my stepmother’s house;

Make my bed, mammie, now!

Make my bed, mammie, now!

Where did you get your dinner,

My bonny wee croodin doo?

I got it in my stepmother’s;

Make my bed, mammie, now, now, now!

Make my bed, mammie, now!

What did she gie ye to your dinner,

My bonny wee croodin doo?

She ga’e me a little four-footed fish;

Make my bed, mammie, now, now, now!

Make my bed, mammie, now!

Where got she the four-footed fish,

My bonny wee croodin doo?

She got in down in yon well strand;

Make my bed, mammie, now, now, now!

Make my bed, mammie, now!

What did she do wi’ the banes o’t,

My bonny wee croodin doo?

She ga’e them to the little dog;

Make my bed, mammie, now, now, now!

Make my bed, mammie, now!

O what became o’ the little dog,

My bonny wee croodin doo?

O it shot out its feet and died!

O make my bed, mammie, now, now, now!

O make my bed, mammie, now!

Ho un cd degli Orion da qualche parte, grazie per la segnalazione ho aggiunto un’altra puntata alla storia

I would like to let you know this version of Lord Randal

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bSM5SwzMOZA