Down by the greenwood side-o è forse la versione più conosciuta della ballata childiana “The Cruel Mother“.

[English version]

Down by the greenwood side-o is the most well-known version of the Cruel Mother ballad.

PAGINA QUADRO con SOMMARIO

Le versioni scozzesi

FINE FLOWERS IN THE VALLEY [Child#20 B]-prima parte

Down by the greenwood side-o

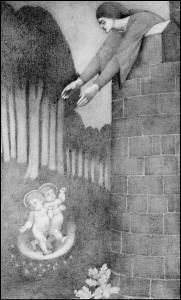

The Cruel Mother: Down by the greenwood side-o

[Child# 20 B/C versione di A.L. Lloyd]

The Cruel Mother [Fiona Hunter]

The Cruel Mother (O the rose and the lindsey) [Ewan MacColl]

The Rose and the Lindsey O ([Old Blind Dogs]

The Cruel Mother: Down by the greenwood side-o

Child# 20 B/C

Down by the greenwood side-o è la versione che ci viene da A.L. Lloyd (1964) ed è una sorta di mixer tra la versione B (“Scots Musical Museum” vol IV, 1792) e la C (“Minstrelsy, Ancient and Modern” William Motherwell 1797)

Lloyd commenta: “La ballata sembra essere vecchia, perché è piena di primitivi concetti della tradizione come il coltello da cui il sangue non potrà mai più essere lavato (mi viene in mente Lady Macbeth). Anche primitiva è l’idea che i morti che non hanno ricevuto la cerimonia che li accoglie pienamente nel mondo dei vivi (in questo caso, il battesimo) non potranno mai essere accolti e incorporati nel mondo dei morti, ma dovranno ritornare a tormentare i vivi. Alcuni studiosi ritengono che The Cruel Mother possa essere stata portata in Inghilterra dagli invasori vichinghi, dal momento che praticamente la stessa storia si trova nella ballata danese (…). Molto probabilmente, è il caso di un’antica fiaba popolare trasformata in una ballata lirica, forse negli ultimi quattrocento anni, e diffusa in varie parti d’Europa, possibilmente con l’aiuto di versioni stampate tutte derivate da un singolo originale (se quell’originale era inglese o danese o in qualche altra lingua, i nostri attuali ricercatori non ce lo dicono).”

Così il finale che rimaneva sospeso nella versione scozzese ‘Fine Flowers In The Valley‘ con l’apparizione dello spirito- fantasma del bambino, qui si conclude con una serie di maledizioni o punizioni rivolte alla madre, mutuate dalla ballata “The Maid and the Palmer” che Child colleziona al numero 21 (“The Well Below the Walley“).

Si introduce anche il dettaglio del pugnale insanguinato che non si riesce più a pulire, simbolo della macchia indelebile che resterà impressa sulla coscienza della donna, un indice puntato che l’accusa!

This version comes from A.L. Lloyd (1964) a sort of mixer between version B (“Scots Musical Museum” vol IV, 1792) and C (“Minstrelsy , Ancient and Modern “William Motherwell 1797)

Lloyd commenting: “The ballad seems to be old, for it is full of primitive folklore notions such as the knife from which blood can never be washed (the instance of Lady Macbeth comes to mind). Also primitive is the idea that the dead who have not undergone the ceremony that initiates them fully into the world of the living (in this case, christening) can never be properly received and incorporated into the world of the dead, but must return to plague the living. Some scholars think The Cruel Mother may have been brought to England by invading Norsemen, since practically the same story occurs in Danish balladry (…). More probably, it is a case of an ancient folk tale being turned into a lyrical ballad, perhaps within the last four hundred years, and spreading in various parts of Europe, possibly with the help of printed versions all deriving from a single original (whether that original was English or Danish or in some other language, our present researchers do not tell us). (from here)

Thus the ending that remained suspended in the scottish version ‘Fine Flowers In The Valley‘ with the appearance of the spirit-ghost of the child, ends here with a series of curses or punishments addressed to the mother, borrowed from the ballad “The Maid and the Palmer “(“ The Well Below the Walley “) -Child #21.

It also introduces the detail of the bloody dagger that can no longer be cleaned, a symbol of the indelible stain that will remain etched on the woman’s conscience.

Traduzione italiana di Cattia Salto

I

Si appoggiò ad un biancospino

tutta sola e così solitaria

e lì fece nascere due bei bambini

ed era dentro al bosco più profondo

E si levò la sua cintura di seta

e li legò mani e piedi.

“Non sorridete così dolcemente miei piccini,

o il vostro dolce sorriso mi farà morire”

Lei aveva un pugnale lungo e appuntito

e lo premette nei loro teneri cuori.

Scavò una fossa sotto il sole

e ci seppellì dentro i teneri bimbi.

Pulì il pugnale nell’erba

e più lo puliva più sangue si vedeva.

Gettò il pugnale lontano

e più lontano lo gettava più vicino ritornava.

II

Mentre camminava verso la chiesa

vide due bei bambini nell’androne

Mentre camminava verso il castello di famiglia

vide due bei ragazzi che giocavano alla palla

“O bambini se foste miei

vi vestirei con bella seta scarlatta”

“Cara madre, quando eravamo tuoi

non ci hai vestiti di bella seta scarlatta!

Hai preso un pugnale lungo e appuntito

e lo hai premuto nel nostro tenero cuore.

Hai scavato una fossa sotto il sole

e ci hai seppellito sotto ad una lastra di marmo”.

“Bambini cosa devo passare

a causa della crudeltà che vi ho fatto?”

“Sette lunghi anni come uccello nel bosco

e sette lunghi anni come pesce nel fiume

sette anni come batacchio della campana

e sette lunghi anni nelle oscurità dell’inferno.”

NOTE

1) probabilmente un prugnolo o un biancospino; Forse un tempo la ballata portava traccia di pratiche antiche ampiamente diffuse (anche i civilissimi Romani consideravano diritto del pater familias decidere sulla sorte del neonato): il bambino era stato esposto e lasciato in dono alle fate (l’indizio ci viene dall’albero scelto per la sepoltura il biancospino l’albero delle fate per eccellenza, la porta tra i due mondi – vedi).

2) il greenwood è la parte del bosco più impenetrabile dove i Celti credevano si celasse l’ingresso dell’AltroMondo (vedi), ma è anche il luogo “fuori legge” fuori dalla società civile dove accadono incontri fatati e illeciti, vengono abbandonati i bambini piccoli o uccisi]

3) contrariamente alla versione precedente la fanciulla scava la fossa alla luce del giorno e in una radura aperta e non sotto l’albero, ci troviamo in una versione “cristianizzata” della ballata che nasconde ogni riferimento all’esposizione dei bambini come dono alle fate. E tuttavia la mancanza del battesimo e di una sepoltura consacrata sembra essere la causa del loro ritorno in forma di spiriti che non troveranno pace finchè la loro madre crudele riceverà la sua punizione all’Inferno

4) il pugnale insanguinato che non si riesce più a pulire è un simbolo nelle antiche ballate provenienti dalla Scandinavia della colpevolezza, le mani si macchiano del sangue innocente e rivelano l’assassino, così nel Medioevo si toccava il cadavere esposto per mostrare la propria innocenza.

5) il gioco della palla è un tipico passatempo dei ragazzi e delle giovinette nelle ballate medievali e veniva praticato nelle vie cittadine o nei parchi dei castelli

6) sette anni è un periodo simbolico per indicare una punizione, un numero utilizzato spesso nelle ballate per indicare un lungo periodo di apprendistato. Il concetto di punizione e penitenza è proprio della religione cattolica che ha istituito il sacramento della confessione.

7) in ogni villaggio c’era una volta una campana preposta per essere suonata vigorosamente in caso di allerta (un attacco nemico, un incendio) o per chiamare la gente a raccolta

Down by the greenwood side-o (A.L. Lloyd version)

I

She leaned herself against a thorn (1) –

All alone and so lonely,

And there she had two pretty babies born,

And it’s down by the greenwood side-o (2).

And she took off her ribbon belt,

And there she bound them hand and leg.

“Smile not so sweet, by bonny babes,

If you smile so sweet, you’ll smile me dead.”

She had a pen-knife long and sharp,

And she pressed it through their tender hearts.

She digged a grave beyond the sun (3),

And there she’s buried the sweet babes in.

She stuck her pen-knife on the green (4),

And the more she rubbed, more blood was seen.

She threw the pen-knife far away,

And the further the threw the nearer it came.

II

As she was going by the church,

She seen two pretty babies in the porch.

As she came to her father’s hall,

She seen two pretty babes playing at ball (5).

“Oh babes, oh babes, if you were mine,

I’d dress you up in the scarlet fine.”

“Oh mother, oh mother, we once were thine,

You didn’t dress us in scarlet fine.

You took a pen-knife long and sharp,

And pressed it through our tender heart.”

“You dug a grave beyond the sun,

And buried us under a marble stone.”

“Oh babes, oh babes, what have I to do,

For the cruel thing that I did to you?”

“Seven long years (6) a bird in the wood,

And seven long years a fish in the flood.”

“Seven long years a warning bell (7),

And seven long years in the deeps of hell.”

FOOTNOTES

1) probably a blackthorn or hawthorn; perhaps once the ballad bore traces of widely spread ancient practices (even for the civilized Romans the pater familias had right to decide on the fate of the newborn): the child had been exposed and left as a gift to the fairies (the clue comes from the chosen tree for the burial, the hawthorn or the fairy tree par excellence, the door between the two worlds (cf)

2) the greenwood is the part of the most impenetrable wood where the Celts believed it was hidden the entrance of the Other World , but it is also the “outlawed” place outside civil society where the fairies meet the human and small children are abandoned or killed

3) contrary to the previous version, the girl digs the grave in the daylight and in an open glade and not under the tree, we find ourselves in a “Christianized” version of the ballad that hides any reference to the exposure of children as a gift to fairies. And yet the lack of baptism and a consecrated burial seems to be the cause of their return in the form of spirits who will not find peace until their cruel mother receives her punishment in Hell

4) the bloody dagger that can no longer be cleaned is a symbol in the ancient ballads from Scandinavia of guilt, the hands are stained with innocent blood and reveal the murderer, so in the Middle Ages the exposed corpse was touched to show their innocence

5) the game of the ball is a typical pastime of boys and girls in medieval ballads and was practiced in the city streets or in the parks of the castles

[il gioco della palla è un tipico passatempo dei ragazzi e delle giovinette nelle ballate medievali e veniva praticato nelle vie cittadine o nei parchi dei castelli]

6) seven years is a symbolic period to indicate a punishment, a number often used in ballads to indicate a long period of apprenticeship. The concept of punishment and penance is proper to the Catholic religion which established the sacrament of confession.

7) in each village there was once a bell designed to be sounded vigorously in the event of an alert (an enemy attack, a fire) or to call people to gather

“Down by the greenwood side-o” viene dalla versione testuale di A.L. Lloyd, e la melodia è un sussurro inquietante, ma la ridondanza delle ripetizioni appesantiscono la storia e fanno apparire il testo, a mio avviso, meno “bello” della precedente versione.

“Down by the greenwood side-o” from A.L. Lloyd version, the melody is a disturbing whisper. The redundancy of the repetitions weigh down the story and make the text appear, in my opinion, less “beautiful” than the previous version.

Down by the greenwood sidie-o

Negli archivi di Tobar an Dualchais sono registrate almeno 5 versioni della Doon by the greenwood sidie o, raccolte nell’Aberdeenshire tra cui quella di Lucy Stewart (1952)

In the archives of Tobar an Dualchais we have at least 5 versions of the Doon by the greenwood sidie o, recorded in Aberdeenshire, including that of Lucy Stewart (1952)

Traduzione italiana di Cattia Salto

I

Fu nei boschi e nelle colline del Logan

dove aiutai la mia bella ragazza con i vestiti

prima le calze e poi le scarpe

ma prima che finisse lei mi sfuggì

II

Si sollevò il mantello sulla testa

e andò a compiere il suo misfatto

andò a compiere il suo misfatto

nel bosco più profondo

III

Appoggiò la schiena ad un biancospino

e fece nascere due bei bimbi

due bei bimbi fece nascere

nel bosco più profondo

IV

Si levò il nastro di seta dai capelli

e li soffocò sebbene piangessero tanto

li soffocò sebbene piangessero tanto

nel bosco più profondo

V

Scavò una fossa sotto l’albero

e li seppellì dove nessuno potesse vedere

li seppellì dove nessuno potesse vedere

nel bosco più profondo

VI

Quattro giorni e notti stette in travaglio

affinchè nessuno s’immischiasse del suo buon nome, nessuno s’immischiasse del suo buon nome,

nel bosco più profondo

VII

Quattro giorni e notti divenne pallida e smunta

e quanto soffrì nessuno lo sa

quanto soffrì nessuno lo sa

nel bosco più profondo

VIII

Guardava dagli spalti del castello

e vide due bei ragazzi che giocavano alla palla

vide due bei ragazzi che giocavano alla palla

nel bosco più profondo

IX

“O bambini, bambini se foste miei

vi nutrirei di latte e vino

vi nutrirei di latte e vino

nel bosco più profondo

X

“Oh Madre, madre quando eravamo tuoi

non ci nutrivi con latte e vino

non ci nutrivi con latte e vino

nel bosco più profondo

XI

Ma prendesti un nastro dai capelli

e ci soffocasti sebbene piangessimo tanto

ci soffocasti sebbene piangessimo tanto

nel bosco più profondo

XII

O bambini, bambini ditemi la verità

quale sarà il futuro per voi

quale sarà il futuro per voi

nel bosco più profondo

XIII

Mentre noi due dimoriamo in paradiso

tu dovrai affrontare i tormenti dell’inferno

tu dovrai affrontare i tormenti dell’inferno

nel bosco più profondo

NOTE

da Up Yon Wide and Lonely Glen (Elisabeth Stewart) con trascrizione della versione di Fiona Hunter (cf)

1) nel frammento Logan Water,

“Ae simmer night, on Logan braes,

I help’d a bonnie lass on wi’ her claes,

First wi’ her stockings, an’ syne wi’ her shoon

But she gied me the glaikst when a’ was done I”

quindi sh(o)een=shoon= shoe

2) to give one’s slip= sfuggire, svignarsela

3) credo voglia dire “Si sgravò da sola perchè nessuno avesse da ridire sul suo buon nome”

Fiona Hunter version

I

It’s Logan’s wids an Logan’s braes

Whaur I helped ma bonnie lassie on wi her claes

first her hose an then her sheen (1)

she’s gaen me the slip (2) when she wis deen.

II (omitted)

She’s taen her cloak aboot her heid

An she’s gaun tae dae a gruesome deed

she’s gaun tae dae a gruesome deed

Down by the greenwood sidie-o

III

She’s leaned her back against a thorn

an there she has twa bonnie bairnies born

there she has twa bonnie bairnies born

Down by the greenwood sidie-o

IV

She’s taen her ribbon fae aff her hair

an she’s chokit them tho they grat sair

she’s chokit them tho they grat sair

Down by the greenwood sidie-o

V

She’s dug a hole beside a tree

an she’s beeriet them whaur there’s nane can see

she’s beeriet them whaur there’s nane can see

Down by the greenwood sidie-o

VI

Four days and nichts she bore her bairn, (3)

So that nane could meddle wi her gweed name;

Nane could meddle wi her gweed name,

Down by the greenwood sidie-o.

VII

Four days and nichts she grew wan and pale

an what ailed her noo there’s neen could tell

what ailed her noo there’s neen could tell

Down by the greenwood sidie-o

VIII

She’s lookit ower the castle waa

an she’s seen twa bonnie bairnies playin af the baa

she’s seen twa bonnie bairnies playin af the baa

Down by the greenwood sidie-o

IX

Oh bairnies bairnies if you were mine

a wid hae fed you the white coo milk and wine

a wid hae fed you the white coo milk and wine

Down by the greenwood sidie-o

X

Oh mother, mother when we were thine

You didna feed us on he white coo milk and wine

You didna feed us on he white coo milk and wine

Down by the greenwood sidie-o

XI

But you took a ribbon fae aff yer hair

an you chokit us tho we grat sair

you chokit us tho we grat sair

Down by the greenwood sidie-o

XII

Oh bairnies bairnies come tell me truth

what’s the future are for you

what’s the future are for you

Down by the greenwood sidie-o

XIII

While we two now in heaven do dwell

you’ve got tae face the fierce fires o hell

you’ve got tae face the fierce fires o hell

Down by the greenwood sidie-o

[scottish lyrics from Up Yon Wide and Lonely Glen (Elisabeth Stewart) with transcription of Fiona Hunter version (cf)]

Fiona Hunter in Cruel Mother, 2014 video directed and animated by Gavin C Robinson

Fiona Hunter nella sua interpretazione di “Doon by the greenwood sidie o” riprende la versione di Lucy Steward come appresa dalla sua mentore Alison McMorland. Nel video la madre e i bambini sono raffigurati come dei barbagianni stilizzati nella faccia a cuore

Fiona Hunter takes up the version of Lucy Steward -she learned it from her mentor Alison McMorland. In the video, the mother and children are depicted as stylized barn owls

Fiona Hunter – Cruel Mother from Gavin C Robinson on Vimeo.

The Cruel Mother (O the rose and the lindsey)

In questa terza versione scozzese alla storia si aggiunge una specie di introduzione per contestualizzarla: la fanciulla (a volte figlia di re o comunque di nobili origini) che vive nel nebbioso Nord è stata sedotta da un cortigiano o un servitore (un false-lover che voleva solo divertirsi sessualmente con lei).

La versione sembrerebbe derivare dalla “The Lady of York” secondo alcuni la versione originale della ballata (o una delle versioni più antiche)

A kind of introduction is added to the story to contextualize it: the girl (sometimes the king’s daughter or in any case of noble origins) who lives in the foggy North was seduced by a courtier or a servant (a false-lover who just wanted to have fun sexually with her).

The version seems to derive from “The Lady of York“, according to some the original version of the ballad (or one of the older versions)

Traduzione italiana di Cattia Salto

I

C’era un bella fanciulla che viveva nel Nord

oh, la rosa e il giglio

che si innamorò di un servo di suo padre

laggiù nel verde bosco-o

Lui la corteggiò per un anno e un giorno

finchè lui tradì la giovane ragazza

Appoggiò la schiena contro il biancospino

e lì fece nascere due bambini

e prese il suo stiletto ben affilato

e trafisse quei due bimbi al cuore.

II

Mentre camminava verso il palazzo del padre

vide due ragazzi che giocavano alla palla

“O bambini se foste miei

vi vestirei con bella seta”

“Cara madre, quando eravamo tuoi

non ci trattasti così bene!”

“Ahimè, Bambini allora ditemi

di che morte devo morire”

“Sette anni come pesce nel fiume

sette anni come uccello nel bosco

sette anni come batacchio nella campana

sette anni nelle fiamme dell’inferno.”

“Benvenuto pesce nel fiume

benvenuto uccello nel bosco

benvenuto batacchio nella campana,

ma che Dio mi salvi dalle fiamme dell’inferno”

NOTE

1) il Nord è più di un luogo geografico è una parola in codice che avvisa gli ascoltatori che sta per essere narrato qualcosa di triste e oscuro

2) [Lindsay scritto in vari modi potrebbe stare per “linseed” cioè il seme del lino che in inglese si dice “flax”. O più precisamente una contrazione o storpiatura della parola Linsey-Woolsey (che però in scozzese si dice Wincey) lin è la parola arcaica per lino + lana ossia un tessuto grossolano misto lino indossato dai contadini. Su Mudcat (qui) qualcuno fa notare che il clan scozzese degli Ó Loinn (O’Lynn, Lynn, Lind, Linn, Lynd, Lindsay), ha come emblema la ruta e il tiglio, peccato però che il Crest del Clan sia un cigno che spunta da una corona; tuttavia leggendo nelle pagine del sito ufficiale del “Clan Lindsay Society” si legge che il Tiglio è un albero che simboleggia il clan come pure la Ruta, definita come plant badge del Clan. Ma se chi canta vuole dire al suo pubblico che l’amore libero porta a gravidanze indesiderate (e al rimpianto) avrebbe utilizzato tranquillamente il simbolismo della ruta. E del resto “linden” è il nome del tiglio (senza scomodare nessun emblema di clan) e molti sono propensi a seguire questa traduzione. Malcom Douglas così riporta “Annie G Gilchrist (Journal of the Folk-Song Society VII (22) 1919, 82) ipotizzò che la ballata potesse essere stata “portata in Gran Bretagna dagli Uomini del Nord” e continua, ‘the “rose and the lindie” suggerisce la corruzione di un ritornello norvegese in cui troviamo la parola “rosenlund” – “rosenlund” (letteralmente legno di rosa) secondo Dr Prior (Ancient Danish Ballads, Introduction, p xxxvi) è l’equivalente esatto del nostro “greenwood” e, come questo, la scena di molte ballate.” Ovviamente, ciò presuppone che le forme danesi della storia siano più antiche di quelle britanniche “.

Un ulteriore significato del verso vede il temine lino come metafora per indicare i capelli biondi: “flaxen hair” o lint-white (in scozzese) è una sfumatura di giallo chiaro che tende al dorato, quindi il verso è come se descrivesse la fanciulla dal pallido incarnato e dai capelli biondi. O potrebbe essere una storpiatura per lily: non dimentichiamo che nella ballate celtiche la rosa è un fiore infausto e il giglio è la prefigurazione della morte]

3) un anno e un giorno è la durata dei matrimoni di “prova” presso i Celti e per scioglierli bastava che i due si dividessero andando in direzioni opposte nella notte di Beltane

4) qui si accenna ad un vago tradimento, in altre versioni si parla più esplicitamente della gravidanza in stato avanzato che ha fatto scappare il “corteggiatore”

5) probabilmente un prugnolo o un biancospino; possiamo dedurre che siamo agli inizi della bella stagione poiché con lo spino del maggio si festeggiava fin dai tempi antichi l’arrivo della Primavera.

Ewan MacColl version

I

There was a fair maid lived in the north (1)

O the rose and the lindsey O (2)

O She fell in love with her father’s serf

Down by the Greenwood sidey-o

He courted her for a year and a day (3)

Till he, the young girl, did betray (4)

She leaned her back up against the thorn (5)

And there she had two little babes born

She took her pen knife clean and sharp

And pierced those two babes to the heart

II

As she was walking her father’s hall

She spied two boys a-playin’ ball

She said, “O babes if thou were’t mine

I’d dress you up in silk so fine”

“Ah, mother dear, when we were thine

You did not treat us then so fine”

She said, “Ah babes ‘tis you can tell

What kind of death I’ll have to die”

“Seven years (8) a fish in the flood

Seven years a bird in the wood

Seven years a tongue in the mourning bell

Seven years in the flames of hell”

“Welcome, welcome, fish in the flood

Welcome, welcome, bird in the wood

Welcome tongue in the mourning bell

God, save me from the flames in hell”

FOOTNOTES

1) the North is more than a geographical place, it is a code word that warns the audience that something sad and dark is about to be told

2) Lindsay written in various ways could stand for “linseed” ie the seed of the flax which in English is called “flax”. Or more precisely a contraction or distortion of the word Linsey-Woolsey (which however in Scottish is said Wincey) lin is the archaic word for linen + wool or a coarse linen mixed fabric worn by peasants. On Mudcat (here) someone points out that the Scottish clan of Ó Loinn (O’Lynn, Lynn, Lind, Linn, Lynd, Lindsay), has as an emblem the rue and the linden, too bad that the Crest of the Clan is a swan that appears from a crown; however reading in the pages of the official site of the “Clan Lindsay Society” we read that the Tiglio is a tree that symbolizes the clan as well as the Ruta, defined as plant badge of the Clan. But if the singer wants to tell his audience that free love leads to unwanted pregnancies (and regret) he would have safely used the symbolism of rue. And besides “linden” is the name of the lime tree (without disturbing any clan emblem) and many are inclined to follow this translation. Malcom Douglas thus reports “Annie G Gilchrist (Journal of the Folk-Song Society VII (22) 1919, 82) conjectured that the ballad might have been brought to Britain by the Northmen ‘and continued,’ the” rose and the lindie suggests a corruption of a Norse refrain in which the word “rosenlund” occurs – “rosenlund” (literally rose wood) according to Dr Prior (Ancient Danish Ballads, Introduction, p xxxvi) being the exact equivalent of our “greenwood,” and, like it, the scene of many ballad adventures. ‘ Of course, that pre-supposes that the Danish forms of the story are older than British “.

A further meaning of the verse sees the term linen as a metaphor to indicate blond hair: “flaxen hair” or lint-white (in Scottish) is a shade of light yellow that tends to gold, so the verse is as if describing the girl from pale complexion and blond hair. Or it could be a cripple for lily: let’s not forget that in the Celtic ballads the rose is an inauspicious flower and the lily is the prefiguration of death

3) a year and a day is the duration of “trial” marriages with the Celts and to dissolve them it was enough for the couple to divide going in opposite directions on Beltane night

4) here the mention of a vague betrayal, in other versions they speak more explicitly of the advanced pregnancy that made the “suitor” run away

5) probably a blackthorn or hawthorn; we can deduce that we are at the beginning of the summer because with the May thorn, the arrival of Spring was celebrated since ancient times

Shirley Collins crive nelle note di copertina dell’album: “Questa warning ballad ha tutto, incluso una grande melodia. Ewan MacColl me l’ha insegnata quando avevo vent’anni. Un inizio piano e documentario, che riporta il gesto privato di una giovane ragazza lacerata nella coscienza. Poi il confronto della giovane madre con i fantasmi dei suoi gemelli assassinati e la sua dannazione. Il ritornello ha la qualità di un incantesimo, innalzando un miserabile essere umano all’archetipo del rimorso.“

Shirley Collins writes in the liner notes of her album:” This cautionary ballad has everything, including one of the greatest of tunes. Ewan MacColl taught it to me when I was twenty. A flat, documentary opening, reporting a private act by conscience-torn young girl. Then the confrontation of the young mother by the ghosts of her murdered twin babies, and her damnation. The refrain has the quality of an incantation, raising one wretched human being to an archetype of remorse.” (from here)

The Rose and the Lindsey O

Traduzione italiana di Cattia Salto

C’era un donna che viveva nel Nord

evviva la rosa e il giglio

che si innamorò di un servo di suo padre

laggiù nel bosco più verde

Lei fu corteggiata da lui per un anno e un giorno

finchè la grande pancia di lei la tradì

Si appoggiò di schiena ad un albero

pensando di alleggerirsi un po’,

si appoggiò ad un biancospino,

belli erano i bambini che fece nascere,

e tirò fuori il suo stiletto

e trafisse e mise fine alla loro piccole vite.

Li seppellì sotto a una pietra di marmo

pensando di ritornare a casa fanciulla.

Guardava oltre alle mura del palazzo del padre,

e vide due bei ragazzi che giocavano alla palla

“O bei bambini se foste miei

vi vestirei con bella seta”

“Cara madre, quando eravamo tuoi

non ci hai trattato così bene!”

“Bambini allora ditemi

di che morte devo morire”

“Sette anni uccello nel bosco

sette anni come pesce nel fiume

sette anni come batacchio della campana,

sette anni nelle fiamme dell’inferno.”

“Benvenuto uccello nel bosco

benvenuto pesce nel fiume

benvenuto batacchio della campana,

ma Dio mi salvi dalle fiamme dell’inferno”

Registrano l’album solo in quattro Ian F. Benzie voce e chitarra, Jonny Hardie violino, Buzzby McMillian basso, Davy Cattanach percussioni.

Nelle note di copertina si legge: “Basato sulla versione trovata nella raccolta delle Ballate di Child, potrebbe essere una raccolta di diverse versioni di Child, ma è molto simile, ad esempio, alla versione che Gordeanna MacCulloch ha imparato da Norman Buchan, che a sua volta (secondo Ailie Munroe, “The Folk Music Revival in Scotland”, 1984) è molto simile alla versione di “Last Leaves of the Traditional Ballads and Ballad Airs” (Alexander Keith, 1925); Vorrei che le persone fossero un po’ meno misteriose nelle loro note di copertina: potremmo quindi farci un’idea da dove prendono il loro materiale, di quanto abbiano aggiunto per loro conto… “

Old Blind Dogs version

There was a lady in the North,

Hey wi’ the rose and the Lindsey O

And she’s fa’an in love wi’ her faither’s clerk,

Doon by the Greenwood sidey O

She’s coorted him for a year and a day

’Til it’s her great belly did her betray.

She’s leaned her back against a tree

Thinkin’ that she micht lichter be.

And she’s leaned her back against a thorn

And it’s bonnie was the boys she’ born.

But she’s ta’en oot her wee penknife

And she’s pit an end tae their sweet lives.

She’s buried them ’neath a marble stane

Thinkin’ tae gang a maiden hame.

She’s lookit ower her faither’s wa’

And she’s seen thae twa bonnie boys playin’ at the ba’.

“Oh bonnie bairns gin ye were mine

I wad dress ye up in the silk sae fine.”

“Oh cruel mither when we were thine

We nivver saw ocht o’ the silk sae fine.”

“Oh bonnie bairns come tell tae me

Fit kind o’ a death I’ll hae tae dee.”

“Seven years a bird in the wood

Aye an’ seven years a fish in the flood.

“Seven years a turn tae the warnin’ bell

Aye but seven years in the caves o’ hell.”

Welcome welcome bird in the wood

Aye and welcome welcome fish in the flood.

Aye an’ welcome turn tae the warnin bell

But God keep me oot o’ the flames o’ hell.

They record the album in only four: Ian F. Benzie voice and guitar, Jonny Hardie violin, Buzzby McMillian bass, Davy Cattanach percussion

“Based on the version found in the Child collection of Ballads”, it may well be a collation of several of the Child versions, but it’s really quite close to, for example, the version that Gordeanna MacCulloch learned from Norman Buchan, which in turn (according to Ailie Munroe, “The Folk Music Revival in Scotland”, 1984) is very much like the version in “Last Leaves of the Traditional Ballads and Ballad Airs” (Alexander Keith, 1925); I do wish that people would be a bit less mysterious in their sleeve-notes: we might then have some sort of idea where they got their material, and how much of it they made up themselves…”

Part Three- terza parte continua

LINK

http://www.bluegrassmessengers.com/1history-symbol-and-meaning-in-the-cruel-mother.aspx

http://www.bluegrassmessengers.com/english-and-other-versions-20-the-cruel-mother.aspx

http://71.174.62.16/Demo/LongerHarvest?Text=ChildRef_20

https://mainlynorfolk.info/lloyd/songs/thecruelmother.html

http://www.tobarandualchais.co.uk/en/fullrecord/67142/6;jsessionid=F638B924A35919FA29C0E9ABFF279F62

http://www.bluegrassmessengers.com/the-cruel-mither–higgins-aberdeen-1973.aspx

https://www.springthyme.co.uk/ah03/ah03_11.htmhttps://mudcat.org/thread.cfm?threadid=16241