Poor Old Man è il titolo di una sea shanty conosciuta anche come Poor old Horse o Dead Horse che veniva cantata durante una curiosa cerimonia praticata all’epoca dei grandi velieri.

“Paying off the Dead Horse” si traduce in italiano come “pagare il cavallo morto”. Il buffo nome deriva forse da una consuetudine nelle trattative tra gli allevatori: una volta che l’accordo era sancito con una stretta di mano non c’era più modo di tornare indietro anche se il cavallo moriva subito dopo. “Flogging a dead horse” oppure “beating a dead horse” è entrato nei modi di dire ottocenteschi per indicare un modo di fare che non ha prospettive o sbocchi (è inutile frustare un cavallo quando è morto perchè non si risolleverà mai più).

Ma “to work (for) the dead horse” vuol dire sprecare il denaro per comprare cose inutili (come un cavallo morto).

LAVORARE PER IL CAVALLO MORTO

Nel gergo marinaresco il termine “Working off the Dead Horse” si riveste ancora di un ulteriore significato come ci spiega Italo Ottonello: “al marinaio veniva versato un anticipo pari a tre mesi di paga al momento della firma del contratto di lavoro (che avrebbe ricevuto per intero solo alla fine dell’ingaggio prima di sbarcare dalla nave), ma a garanzia del rispetto del contratto, era erogato in forma di pagherò, esigibile tre giorni dopo che la nave aveva lasciato il porto, “sempre che detto marinaio sia salpato con detta nave”. Tutti, invariabilmente, correvano a cercare qualche ‘squalo’ compiacente che comprasse il loro pagherò ad un valore scontato, di solito del quaranta per cento, con molta parte dell’importo fornito in natura.”

Così dell’anticipo non restava niente, spesso prima ancora dell’imbarco, vuoi per comprare gli equipaggiamenti personali (stivali, cerate, coltelli etc che erano a carico del marinaio) oppure più comunemente scialati con donne e “drink” prima della partenza.

E allora il marinaio lavorava per il primo mese per “niente” cioè per “il cavallo morto”; altri invece intendono che è il marinaio ad essere un cavallo sfruttato perchè nel primo mese sulla nave non lavora per sè, ma per i suoi creditori.

A suffragio della prima ipotesi c’è chi sostiene che un tempo il conducente di un cavallo che fosse alle dipendenze di un capo era responsabile della morte del cavallo e non avrebbe più percepito lo stipendio finchè non avesse ripagato il costo del cavallo.

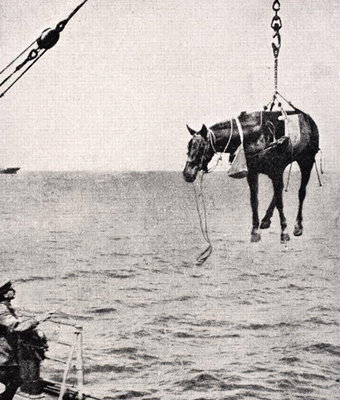

CAVALLO SUL PONTE ALL’ASTA!

A bordo dei vascelli a vela aveva luogo una curiosa cerimonia dopo circa un mese di navigazione: un cavallo era assemblato con gli oggetti di scarto (vele usurate, vecchi barili e corde usurate) e trascinato in giro per il ponte della nave; si apriva quindi un’asta con il banditore che decantava le buone qualità dell’animale, alla fine il cavallo era issato con una corda sul pennone più alto e gettato in mare, mentre veniva cantato come requiem l’ultima parte della melodia di una canzone detta “Paying off the dead horse”.

[English translation]

The Dead Horse is a sea shanty aka Poor old Horse or Poor Old Man about a curious ceremony that took place aboard the sailing vessels.

“Paying off the Dead Horse” perhaps derives from a custom in negotiations between breeders: once the agreement was sanctioned with a handshake there was no way to go back even if the horse died soon after.

“Flogging a dead horse” or “beating a dead horse” has entered the nineteenth-century ways of saying to indicate a way of doing that has no prospects or outlets (it is useless to whip a horse when it is dead because it will never rise again).

But “to work (for) the dead horse” means wasting money to buy useless things (like a dead horse).

Working off the Dead Horse

“Working off the Dead Horse” still has a further meaning in marine jargonas, explained by Italo Ottonello: “at the signing of the recruitment contract for long journeys, the sailors received an advance equal to three months of pay which, to guarantee the respect of the contract, it was provided in the form of “I will pay”, payable three days after the ship left the port, “as long as said sailor has sailed with that ship.” Everyone invariably ran to look for some complacent sharks who bought their promissory note at a discounted price, usually of forty percent, with much of the amount provided in kind.“

So often there was nothing left of the advance, spended for the personal equipment (boots, wax, knives etc that were charged to the sailor) or more commonly for women and “drinks”.

Thus the sailor worked for the first month for “nothing” that is for “the dead horse”; others mean that it is the sailor who is an exploited horse because in the first month on the ship he does not work for himself, but for his creditors.

In support of the first hypothesis there are those who maintain that once the driver of a horse who was employed by a chief was responsible for the death of the horse and would no longer receive his salary until he repaid the cost of the horse.

HORSE ON THE DECK AT THE AUCTION!

A curious ceremony took place aboard the sailing vessels: a horse was assembled with discarded objects (stitched worn sails, old barrels and worn ropes) and dragged around the deck of the ship; then an auction was opened with the auctioneer who praised the good qualities of the animal, at the end the horse was hoisted with a rope on the highest flagpole and thrown into the sea, while the last part of a song’s melody was sung as requiem,

called “Paying off the dead horse”.

BURYING THE DEAD HORSE

Secondo Stan Hugill “La cerimonia divenne una vicenda piuttosto raffazzonata negli ultimi giorni della navigazione a vela, mentre in passato è stato un evento spettacolare, in particolare sulle navi degli emigranti, e una delle migliori descrizioni è data in “Reminiscences of Travel in Australia, America, and Egypt” di R Tangye”

La cerimonia è così descritta da Richard Tangye: “Dopo un mese in mare i marinai eseguivano la cerimonia chiamata “Seppellire il cavallo morto”, spiegazione è questa: prima di lasciare il porto i marinai vengono pagati con un mese di anticipo, in modo da consentire loro di lasciare dei soldi alle mogli, o per acquistare della nuova attrezzatura, ecc., e avendo speso i soldi considerano il primo mese trascorso per niente e quindi lo chiamano “Lavorare per il cavallo morto”.

L’equipaggio veste una figura per rappresentare un cavallo; il suo corpo è fatto con una botte, le sue estremità di fieno o di paglia sono ricoperte di tela, la criniera e una coda di canapa, gli occhi due bottiglie di birra [ginger beer], a volte piene di fosforo. Al termine, il nobile destriero viene messo su una scatola, coperta da un tappeto, e la sera dell’ultimo giorno del mese un uomo sale sulla schiena e viene trainato in giro per la nave dai suoi compagni, al canto della seguente canzoncina:

oh! ora, povero Cavallo, è giunto il tuo momento;

E lo diciamo, perché lo sappiamo.

Oh! molte gare sappiamo che hai vinto,

povero vecchio.

Hai fatto molta strada,

e lo diciamo, perché lo sappiamo.

Per essere arrivato a questo giorno,

Povero Vecchio.

Ora stai per dire addio,

e lo diciamo, perché lo sappiamo.

Povero vecchio cavallo, stai per morire,

povero vecchio.

Dopo aver sfilato sui ponti per richiamare il pubblico, viene annunciata la vendita all’asta del cavallo e un uomo dalla parlantina sciolta monta sul podio e inizia a lodare il nobile animale, dando il suo pedigree, ecc., dicendo che era un buon camminatore, perché aveva fatto 6000 miglia nell’ultimo mese! Poi inizia l’asta, ogni offerente è responsabile solo dell’importo del suo anticipo sull’ultima offerta. Dopo la vendita, il cavallo e il suo cavaliere corrono verso il pennone tra forti applausi. Vengono sparati dei fuochi d’artificio e l’uomo scende dalla schiena del cavallo e, tagliando la corda, lo fa cadere in acqua.

Poi viene cantato il requiem con la stessa melodia di prima.

Ora è morto e non morirà più,

e lo diciamo, perché lo sappiamo.

Ora se n’è andato e non verrà più;

Povero vecchio.

Dopodiché il banditore e il suo assistente procedono a raccogliere le “offerte” e se nella tua ignoranza del galateo dell’asta dovessi offrire le tue al banditore, lui le rifiuta educatamente e ti rimanda al suo assistente!

Una descrizione ancora più sfarzosa ed articolata della cerimonia nell’Harper’s Weekly The Dead Horse Festival New York, 11 novembre, 1882 (qui)

Nelle versioni più tarde della cerimonia tuttavia il rituale diventa più sbrigativo e meno curato, dalla descrizione di Frank T. Bullen risulta che il fantoccio è solo un insieme raffazzonato di materiale di scarto che viene semplicemente issato e fatto cadere in fiamme in mare.

Nel rituale riecheggiano antichi riti propiziatori e benaugurali come quelli del Poor Old Horse natalizio o primaverile (hobby horse) che si svolgevano in Gran Bretagna. (continua) IL cavallo è simbolicamente l’offerta alle “divinità” del mare per placarlo e garantire un viaggio sicuro e fruttuoso.

“The ceremony … became a rather half-hearted affair in the latter days of sail, whereas in days gone by it was a spectacular effort, particularly in the emigrant ships, and one of the best descriptions is given in Reminiscences of Travel in Australia, America, and Egypt,by R Tangye (London, 1884).” (Stan Hugill)

Thus R Tangye writes : “Being a month at sea the sailors performed the ceremony called ” Burying the Dead Horse,” the explanation of which is this: Before leaving port seamen are paid a month in advance, so as to enable them to leave some money with their wives, or to buy a new kit, etc., and having spent the money they consider the first month goes for nothing, and so call it ” Working off the Dead Horse.”

The crew dress up a figure to represent a horse; its body is made out of a barrel, its extremities of hay or straw covered with canvas, the mane and tail of hemp, the eyes of two ginger beer bottles, sometimes filled with phosphorus. When complete the noble steed is put on a box, covered with a rug, and on the evening of the last day of the month a man gets on to his back, and is drawn all round the ship by his shipmates, to the chanting of the following doggerel:

oh! now, poor Horse, your time is come;

And we say so, for we know so.

Oh! many a race we know you’ve won,

Poor Old Man.

You have come a long long way,

And we say so, for we know so.

For to be sold upon this day,

Poor Old Man.

You are goin’ now to say good-bye,

And we say so, for we know so.

Poor old horse you’re a goin’ to die,

Poor Old Man.

Having paraded the decks in order to get an audience, the sale of the horse by auction is announced, and a glib-mouthed man mounts the rostrum and begins to praise the noble animal, giving his pedigree, etc., saying it was a good one to go, for it had gone 6,000 miles in the past month ! The bidding then commences, each bidder being responsible only for the amount of his advance on the last bid. After the sale the horse and its rider are run up to the yard-arm amidst loud cheers. Fireworks are let off, the man gets off the horse’s back, and, cutting the rope, lets it fall into the water.

The Requiem is then sung to the same melody.

Now he is dead and will die no more,

And we say so, for we know so.

Now he is gone and will go no more;

Poor Old Man.

After this the auctioneer and his clerk proceed to collect the ” bids,” and if in your ignorance of auction etiquette you should offer yours to the auctioneer, he politely declines it, and refers you to his clerk!”

An even more sumptuous and articulated description of the ceremony in the Harper’s Weekly The Dead Horse Festival New York, November 11, 1882 (here)

In later versions of the ceremony, however, the ritual becomes more hasty and less cared for, from Frank T. Bullen’s description it follows that the “horse” is just a patched up set of waste material that is simply hoisted and made to fall burning at sea.

The ritual echoes ancient propitiatory and auspicious rituals such as those of the Poor Old Horse at Christmas or Springtime (see more)

The horse is symbolically the offer to the “divinities” of the sea to appease it and guarantee a safe and fruitful journey.

Thanks so much! I am writing about how the “horses” in the ceremony were made and haven’t seen a photo of one of the creations before. I would really love to find out!

Sorry, I meant the photo of the crew stood with the “Horse”. I’ve tried reverse searching on google but can’t find it.

Unfortunately I have not assigned in the description the origin of the photo, I will try to ask in the groups of sea shanty fans

Hi, do you know where the photograph is from? I haven’t seen another of the actual horse!

https://pixels.com/featured/transferring-horsel-from-ship-to-land-ken-welsh.html

Hi, great photo – where is it from?

Thanks,

Maya

Hi, Maya somewhere on Facebook