a cura di Cattia Salto

Sea Shanties & Sailing ships nasce dalla diffusione dei canti marinareschi nell’età dei grandi vascelli.

Le sea shanties (in italiano “baracche del mare”) erano cantate dai marinai sulle grandi navi a vela, durante i lavori più faticosi o monotoni che richiedevano uno sforzo coordinato e collettivo. Ad esempio per levare l’ancora, per sollevare e abbassare le velature e per manovrare le vele..

[English version]

Sea Shanties & Sailing ships was born due to the spread of sea songs in the Golden age of sailing ships.

The sea shanties were sung by sailors on large sailing ships, during the most tiring or monotonous jobs that required a coordinated and collective effort. For example to raise the anchor, to raise and lower the sailings and to maneuver the sails.

Sommario

Why the name shanty/shanties?

The Golden Age of Sailing ships

Herman Melville: sea shanties

Sailing ship

Seas Routes for Sail ships

Sea shanties for working

Working to a rhythm

Sea shanties melodies

Minstrel songs

Shantyman

Folk and pirate circuit

A-Z LIST OF ALL SEA SHANTIES

Perchè shanty/shanties?

L’origine del termine shanty (chantey o chanty) risale a metà dell’Ottocento in ambito americano, ma il suo significato è incerto[1] ed è usato più per un’assonanza.

L’era d’oro dei grandi Vascelli

Secondo gli studiosi i marinai iniziarono a cantare le sea shanties sulle navi mercantili solo dopo la fine delle guerre napoleoniche nel 1815 (più precisamente tra il 1830 e il 1870). L’espandersi del commercio transatlantico richiese la costruzione di navi per acque profonde a grande capacità, ad alta velocità e con più alberi.

Herman Melville: sea shanties

« presto mi abituai a questo [modo di] cantare, senza il quale, i marinai non toccano mai una cima. Talvolta, quando accadeva che nessuno iniziasse, e nonostante tutti gli sforzi, l’alaggio sembrava non procedere molto bene, il ‘primo’ inevitabilmente diceva: ‘dunque, uomini, è possibile che qualcuno tra voi non possa cantare? Cominci, dunque e solleviamo il carico’.

Allora uno di loro attaccava, e sicuramente la canzone sarebbe ben valsa il fiato speso per cantarla. Era come se le braccia di ciascuno, come anche le mie, fossero state molto alleggerite dal canto, e con tale allietante accompagnamento, ciascuno fosse riuscito ad alare molto meglio, cosa che accadeva pure a me.

È molto importante, per un marinaio, saper cantare bene, perché acquista grande nomea tra gli ufficiali, e molta popolarità fra i compagni. certi capitani, prima di arruolare un uomo, gli chiedono sempre se è capace di cantare durante gli alaggi». in Redburn, (1849)

Why the name shanty/shanties?

The term “shanty” (also written as chantey or chanty) dates back to the mid-nineteenth century in the Golden Age of American Sail, but its meaning is uncertain, used more for the assonance, than for its etymological value.

The Golden Age of Sailing ships

According to scholars the sailors began to sing sea shanties on sailing ships only after the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 (more precisely between 1830 and 1870). The expansion of transatlantic trade necessitated the development of a particular type of ship: the large-capacity, high-speed, multi-masted deep-water vessel.

Herman Melville: sea shanties

“…I soon got used to this singing, for the sailors never touched a rope without it. Sometimes, when no one happened to strike up, and the pulling, whatever it might be, did not seem to be getting forward very well, the mate would always say, ‘Come men, can’t any of you sing? Sing now and raise the dead.’

And then some one of them would begin, and if every man’s arms were as much relieved as mine by the song, and he could pull as much better as I did, with such a cheering accompaniment, I am sure the song was well worth the breath expended on it.

It is a great thing in a sailor to know how to sing well, for he gets a great name by it from the officers, and a good deal of popularity among his shipmates. Some sea captains, before shipping a man, always ask him whether he can sing out at a rope.”

Herman Melville, Redburn, (1849)

[1] “Non si sa l’origine precisa del termine americano “chantey” che non ha un equivalente francese pur significando ugualmente “canto marinaro utilizzato per ritmare il lavoro a bordo delle navi”. E’ un termine apparso a metà del XIX° secolo, all’inizio ortograficamente scritto “chaunt” e quindi facilmente associabile al verbo “cantare” ma gli Inglesi rifiutarono decisamente questa ipotesi di origine francofona, adottando la scrittura “shanty” e sostenendo piuttosto derivasse dalle capanne in legno dei pescatori antillesi e caraibici chiamate appunto “shanties”. Queste casupole venivano spostate periodicamente su dei rulli di legno tirati da corde da tutta la popolazione del luogo che si incitava con canti di fatica chiamati a loro volta “shanties”.” Flavio Poltronieri

Velieri

(da “L’evoluzione navale” di Raffaele Staiano)

“…Fino a tutto il 1600 non vi era una differenza netta tra nave mercantile e nave militare e anche queste ultime erano armate per difendersi. Nel 1700 i bastimenti mercantili si differenziano nettamente dalle navi da guerra. I bastimenti mercantili assumono dimensioni e forme diverse, si hanno così navi a due alberi, navi a tre alberi, brigantini, golette, tartane, clipper, ecc. …

La vela raggiunse il massimo sviluppo nel 1800. La velatura fu realizzata con un numero sempre maggiore di vele, tutte orientabili in modo da mantenere la rotta voluta anche con venti provenienti da direzione diversa.“

Una sea shanty per ogni manovra

Il numeroso equipaggio era impegnato costantemente nel governo della nave. A partire dall’inizio del viaggio, quando ogni cosa doveva essere imbarcata e sistemata a mano. Una volta salpata l’ancora i marinai erano sulle sartie a serrare e spiegare le vele.

Un altro lavoro costante era quello di sentina con l’azionamento a mano delle pompe. Durante la battaglia ulteriori pompe erano azionate per spegnere gli incendi e per lavare i ponti inondati di sangue. Pulegge e verricelli alleviavano un po’ la fatica ma anche questi erano azionati a mano.

Sailing Ship

(from “The naval evolution” by Raffaele Staiano)

“… Until the whole 1600 there was not a clear difference between merchant ship and military ship and also these last ones were armed to defend themselves. In 1700 the merchant ships differed clearly from the warships. The merchant ships take on different sizes and shapes, so they have two-masted ships, three-masted ships, brigantines, schooners, tartans, clippers, etc. …

The sail reached its maximum development in 1800. The veiling was made with an ever increasing number of sails, all adjustable so as to maintain the desired course even with winds coming from different directions.“

Sea shanties for working

The numerous crew was constantly engaged in the government of the ship. From the beginning of the journey, when everything had to be embarked and arranged by hand. Once the anchor sailed the sailors were on the shrouds to unfurl the sails.

Another constant work was that of bilge with the hand drive of the pumps. During the battle further pumps were operated to extinguish fires and to wash the bridges flooded with blood. Pulleys and winches relieved a bit of fatigue, but these too were operated by hand.

Sea shanty: Una canzone per ogni manovra!

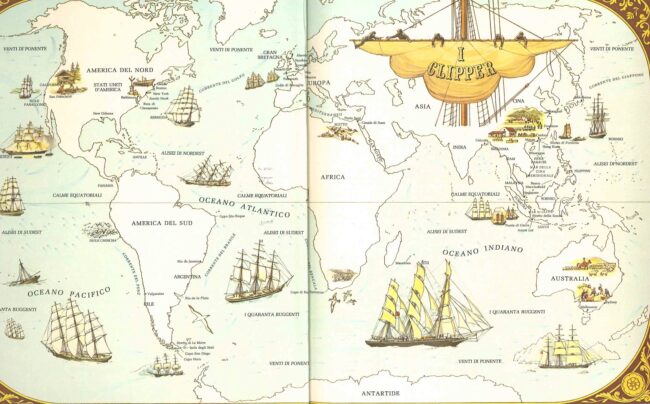

Le rotte dei velieri

I velieri seguivano delle rotte prestabilite tracciate da venti e correnti oceaniche, ad esempio la rotta degli Alisei (i venti costanti tropicali non a caso chiamati anche “trade winds”) era quella seguita nell’Oceano Atlantico dalle coste dell’Europa alla costa est degli Stati Uniti, America centrale e viceversa. Rotte che però variavano a seconda della stagione.

Seas Routes for Sail ships

The sailing ships followed the pre-established routes drawn by winds and ocean currents, for example the trade winds (the tropical constant winds) was that followed in the Atlantic Ocean from the coasts of Europe to the east coast of the United States, Central America and vice versa. Routes that vary according to the season.

.. Quindi partendo ad esempio dall’Inghilterra la rotta era la seguente : Atlantico fino a Capo Verde poi tutto ad Ovest verso i Caraibi quindi a Sud lungo il Brasile e la costa Argentina fino a riprendere i venti portanti che con rotta di nuovo verso Est portano a passare capo di Suona Speranza in Sud Africa e finalmente quella fetenzia di ostico oceano che è quello Indiano. Approssimativamente 30.000 Km quando in linea d’aria sono solo 8.000!

Non che tornare fosse poi più semplice. Rotta su Australia con il passaggio di capo Leeuwin in Nuova Zelanda, quindi oceano fino a doppiare capo Horn. Arrivati all’Africa rotta a Nord di nuovo verso i Caraibi prima delle calme equatoriali e infine a Est passando a Nord delle isole Azzorre. Più o meno altri 36.000 km…

Occorre inoltre tenere bene a mente che queste rotte non sono percorribili sempre durante tutto l’anno. Per fare un banale esempio per andare ai Caraibi la stagione migliore è l’inverno quando l’anticiclone delle Azzorre è stabile e garantisce venti portanti per tutta la traversata. Mentre tornare è sconsigliato durante il periodo estivo per la possibile presenza dei cicloni in zona equatoriale. (tratto da qui)

.. So starting for example from England the route was as follows: Atlantic to Cape Verde then all to the West to the Caribbean and then to the South along Brazil and the Argentine coast to resume the supporting winds that with the route back to the East lead to go head of Suona Speranza in South Africa and finally that tough ocean that is the Indian one. Approximately 30,000 Km when as the crow flies are only 8,000!

Not that it was easier to come back. Sailing on Australia with the passage of Cape Leeuwin in New Zealand, then ocean up to dub Cape Horn. Arrived in Africa, heading north again towards the Caribbean before the equatorial calm and finally to the east passing north of the Azores. More or less 36,000 km .

It is also important to keep in mind that these routes are not always viable throughout the year. To make a trivial example to go to the Caribbean the best season is winter when the Azores anticyclone is stable and guarantees winds for the whole crossing. While returning is not recommended during the summer for the possible presence of cyclones in the equatorial area. (translated from here)

Per darsi un ritmo

Il ritmo è sempre stato importante sulle navi, a cominciare dal suono percussivo dei tamburi con cui si scandiva il tempo dei rematori, nelle prime, modeste navi, e via via sempre più importante nei lavori più complessi per manovrare navi sempre più grandi e con molti alberi e velature.

Si può affermare che furono proprio le grandi navi a vela a rendere comune e quasi “internazionale” la pratica del cantare le sea shanties.

Le melodie

Le Sea Shanties sono considerate semplici filastrocche, improvvisazioni strampalate, eppure così radicate nella cultura marinaresca per ogni specifica tipologia di nave! Secondo un detto comune “una canzone vale dieci uomini a virare l’argano“.

Le influenze che si possono riscontrare nelle sea shanties sono principalmente le melodie popolari tra cui quelle di Irlanda e Scozia, ma soprattutto le melodie e i canti afro-americani provenienti dagli stivatori neri che a loro volta cantavano mentre caricavano manualmente le balle di cotone sui velieri nei porti caraibici e degli Stati Uniti del Sud.

Vero è che sulle navi mercantili inglesi abbondavano uomini provenienti dall’Irlanda, Scozia e Galles e che i canti gioco forza ricalcavano la loro tradizione musicale, in particolare per le forebitter songs (i canti passatempo nelle ore di riposo).

Working to a rhythm

The rhythm has always been important on the sailing ships, starting from the percussive sound of the drums with which the time of the rowers was scanned, in the first, modest ships, and increasingly important in the most complex jobs to maneuver ever larger and larger ships with many trees and veils.

It can be said that it was the sailing ships in the Golden Age of Sail that made the practice of singing sea shanties common and almost “international”.

Sea shanties melodies

The Sea Shanties will be said as simple nursery rhymes, bizarre improvisations, yet so rooted in the seafaring culture for each specific type of Ship! According to a common saying “a song is worth ten men to turn the winch”.

The influences that can be found in sea shanties are mainly the popular melodies including those of Ireland and Scotland, but above all African-Americans coming from black unloaders who in turn sang while manually loading the bales of cotton on sailing ships in the Caribbean ports and United States of the South.

It is true that men from Ireland, Scotland and Wales abounded on British merchant ships, and that play songs were based on their musical tradition, especially for the forebitter songs (the pastime chants during the hours of rest).

MINSTREL SONG

Definiti da Stan Hugill “pseudo Negro ditties” sono i canti dei music halls, le sale da ballo dei saloons dove dei bianchi dalla faccia dipinta di nero facevano la parodia delle caratteristiche attribuite agli afro-americani. Solo dopo la guerra civile (intorno al 1850) ci saranno delle vere e proprie compagnie di neri -che alla fine del secolo contribuiranno alla nascita del blues.

Tra gli shanty riconducibili alle minstrel songs: Johnny Bowker, A Long Time Ago

Defined by Stan Hugill as “pseudo Negro ditties” the Minstrel songs are the songs of the music halls, where white people with black faces made a parody of the characteristics attributed to African-Americans. Only after the civil war (around 1850) we’ll see a real black companies – which at the end of the century will contribute to the birth of the blues.

Among the shanty attributable to minstrel songs: Johnny Bowker, A Long Time Ago

Lo SHANTYMAN

I testi delle sea shanties ovviamente erano semplici, intercambiabili e con ampio spazio all’improvvisazione, strofe con versi ripetuti da allungare o accorciare a seconda della durata del lavoro.

In genere il solista detto shantyman dalla voce forte e baritonale, e dalla battuta pronta, rispettato da tutti, era quello che intonava la strofa seguita dalla risposta corale di tutti gli altri marinai, secondo lo schema detto “chiamata e risposta.

Una parola del ritornello è enfatizzata per indicare il momento in cui i marinai devono alare la cima o eseguire la manovra, è quindi il coro l’elemento principale di questa forma musicale, talvolta è accompagnato da uno strumento musicale (piffero, organetto o violino).

“Gli shantyman sono generalmente orgogliosi della loro reputazione quanto a improvvisazione e originalità, e tentano di non ripetere due volte lo stesso verso. Se la fine della canzone arriverà prima dell’ultimazione del lavoro, essi l’allungheranno con qualcosa di nuovo, o torneranno su una serie di versi banali usata per «tamponare» in tali occasioni.

Questo spiega perchè gli stessi versi, quali goin, round the horn / wish ya never was born (per andare a doppiare l’horn / vorrei che non fossi mai nato) oppure heard the old man say / go ashore and take yer pay (udito il capitano dire / scendi a terra e ritira la paga), appaiono in tanti shanty diversi.

È molto apprezzato, tra loro, chi riesce a strappare una risata ai marinai, a far sembrare il lavoro più leggero, a indurre gli uomini a lavorare sodo…

Gli shanty possono anche fornire ai marinai un mezzo per esprimersi senza paura di punizioni. Un buono shantyman, nel cantare certe canzoni, spesso riesce a fare satira sui superiori, con un linguaggio tanto diretto quanto efficace. Egli sceglie i punti deboli, fisici e morali del capitano o di uno degli ufficiali, consapevole che la responsabilità ricade unicamente sulle sue spalle, e nessun altro corre seri rischi d’essere punito, il coro, su cui si basa l’azione del lavoro, infatti, non è coinvolto, essendo ripetitivo e senza variazioni.” (Italo Ottonello)

THE SHANTYMAN

The sea shanties were obviously simple, interchangeable and with ample space for improvisation, stanzas with repeated verses to be lengthened or shortened depending on the duration of the work.

Generally the soloist called shantyman with a strong and baritone voice, and by the ready beat, respected by everyone, was the one who intoned the stanza followed by the choral response of all the other sailors, according to the scheme “call and response”.

A word of the refrain is emphasized to indicate the moment when the sailors must perform the maneuver, so the choir is the main element of this musical form, sometimes it is accompanied by a musical instrument (pipe, organ or violin) .

The shantymen are generally proud of their reputation for improvisation and originality, and try not to repeat the same verse twice. If the end of the song arrives before the completion of the work, they will lengthen it with something new, or they will return to a series of trivial verses used to “dab” on such occasions.

This explains why the same verses, such as goin, round the horn / wish ya never was born (or to go to round the horn / wish I had never been born) or heard the old man say / go ashore and take yer pay (hearing the captain say / get down and collect the pay), appear in many different shanties.

It is highly appreciated, among them, who manages to snatch a laugh at the sailors, to make the work seem lighter, to induce men to work hard …

The shanties can also provide the sailors a means to express themselves without fear of punishment. A good shantyman, in singing certain songs, often succeeds in making satire on his superiors, with a language as direct as it is effective. He chooses the weak, physical and moral points of the captain or one of the officers, aware that responsibility falls solely on his shoulders, and no one else runs serious risks of being punished, the choir, on which the action of labor is based in fact, it is not involved, being repetitive and without variations. “

(Italo Ottonello)

A-Z list of all Sea Shanties

SEA SHANTIES: raduni folk e pirati

Con le navi a vapore e la meccanizzazione di molte mansioni, la necessità di cantare è venuta meno, ma nel XX secolo il repertorio delle sea shanties, documentato dai veterani in pensione, è sbarcato sulla terra diffondendosi tra i non marinai e gli amanti della musica folkloristica.

“..alcune delle canzoni che ho citato ora sembrano sciocche vedendole scritte. Non sono il genere di canzoni da stampare. Sono canzoni che devono essere cantate in certe condizioni, e dove quelle condizioni non esistono, appaiono fuori luogo. In mare, quando sono cantate nel tranquillo gaettone, o alando le cime, sono le più belle di tutte le canzoni. È difficile scriverle senza emozione, perché sono parte della vita. Non si possono separare dalla vita. Non si può scrivere una parola di loro senza pensare ai giorni andati, o a compagni da molto tempo diventati corallo, o a belle, vecchie navi, una volta così maestose, ora ferro vecchio.” (John Masefield in Sea Songs 1906)

SEA SHANTIES: Folk and pirate circuit

With steam ships and the mechanization of many tasks, the need to sing has failed, but in the twentieth century the repertoire of the sea shanties, documented by retired veterans, has landed on the land spreading among non-sailors and music lovers folk.

“Some of the songs I have quoted seem foolish now that they are written down. They are not the sort of songs to print. They are songs to be sung under certain conditions, and where those conditions do not exist they appear out of place. At sea, when they are sung in the quiet dog-watch, or over the rope, they are the most beautiful of all songs. It is difficult to write them down without emotion; for they are a part of life. One cannot detach them from life, One cannot write a word of them without thinking of days that are over, or comrades who have long been coral, and old beautiful ships, once so stately, which are now old iron.“

John Masefield in Sea Songs 1906