“An tSeanbhean Bhocht” is the Irish for “Poor old woman”, a personification of Ireland, and is a traditional Irish song from the period of the Irish Rebellion of 1798, and dating in particular to the lead up to the French expedition to Bantry Bay, that ultimately failed to get ashore in 1796.

This expedition is known in France as Expédition d’Irlande (1796-1798).

[Traduzione italiana]

“An tSeanbhean Bhocht” in irlandese vuole dire “povera vecchia”, una personificazione dell’Irlanda, ed è il titolo di una canzone tradizionale sulla ribellione irlandese del 1798, in particolare risalente al periodo precedente alla spedizione francese (fallita) a Bantry Bay.

Questa spedizione è conosciuta in Francia come Expédition d’Irlande (1796-1798).

by The Mórrígan [https://wordpress.com/post/celticandhistoryobsessions.music.blog/533]

An tSeanbhean bhocht: historical background

There were two French expeditions, the first to land in Bantry Bay (the fleet set sail from Brest on 15 December 1796), and a second much smaller expeditionary French force under General Jean Humber landed at Killala on August 22nd 1798[1][2]. Both expeditions ultimately failed. Also see “French Expeditions to Ireland (1796-1798)”[3] for a narrative of the events that unfolded including the failed Batavian Republic expedition of 1797 (the Batavian Republic was the Dutch sister republic of the French Republic).

There were then two more French raids in 1798: “a second raid – ie. the first being the one under General Jean Humber referenced above – accompanied by Napper Tandy, came to disaster on the coast of Donegal; while Wolfe Tone[4] took part in a third, under Admiral Jean-Baptiste-François Bompart, with General Jean Hardy in command of a force of about 3,000 men.

In an attempt to keep this article brief, I haven’t gone into too much detail about the historical context, but if you open the reference articles, you can find narrative and links to find out more about the detailed chain of historical events which led up to l’expédition d’Irlande.

Some interesting points though are copied below (also from Edward Rutherfurd’s historical novel “Ireland Awakening”):

1.l’expédition d’Irlande de 1796: once preparations were complete, the French fleet set sail from Brest on December 15, 1796 with approximately 15,000 soldiers on a variety of ships of the line, frigates, and transports. Once at sea, the weather did not co-operate and the French ships were scattered by a storm[3]

2. Rutherfurd in “Ireland Awakening”[5] says that the results of Wolfe Tone’s efforts in France had been quite remarkable. Theobald Wolfe Tone, (born June 20, 1763, Dublin, Ireland —died November 19, 1798, Dublin)[6], was an Irish republican, and in October 1791 he helped found the Society of United Irishmen, a republican society determined to end British rule, and achieve accountable government, in Ireland. He was instrumental in bringing about l’expédition d’Irlande de 1796.

Rutherfurd further says that Tone had really impressed the Directory who governed the new, revolutionary republic. So much so that they had sent not a token contingent but a fleet of 43 ships, carrying 15,000 troops. Equally important, he says, the ships carried arms for 45,000 men. Most importantly, they were under the command of General Hoche, who was the rival of the republic’s rising star, Napoleon Bonaparte.

Louis Lazare Hoche ; 24 June 1768 – 19 September 1797) was a French military leader of the French Revolutionary Wars[1].

Rutherfurd prefaces this by saying that “history furnishes many tantalising moments – turning points when, had it not been for some chance condition, the course of future events might have changed entirely. The arrival, on 22 December 1796 of the French fleet in sight of Bantry Bay, at the south-western tip of Ireland, is one of them“[6]

In conclusion, each French expedition failed to achieve the goal of liberating Ireland, but their failures were due more to poor timing and weather than the superiority of the British navy. General Humbert’s expedition in 1798 successfully landed French troops in Ireland, becoming the only enemy force to land troops on the British Isles in modern history. He defeated the British at the Battle of Castlebar which became known as the “Races of Castlebar” due to the speed of the British retreat[7]. Against all odds, Humbert led his small force halfway across Ireland before being surrounded and defeated by superior British numbers. Had the French Directory acted sooner and in conjunction with the Irish uprising in May of 1798, events may have turned out very differently. In the years following the Irish uprising, Lord Cornwallis led reforms to alleviate some of the underlying causes of the Irish rebellion of 1798, but the Irish would spend another century striving for independence[3].

from Wikipedia

Ci furono due spedizioni francesi, la prima verso Bantry Bay (la flotta salpò da Brest il 15 dicembre 1796), e una seconda molto più piccola sotto il generale Jean Humber che sbarcò a Killala il 22 agosto 1798[1][2]. Entrambe le spedizioni alla fine fallirono. Si vedano anche “Spedizioni francesi in Irlanda (1796-1798)”[3] per una narrazione degli eventi che si svolsero, inclusa la fallita spedizione della Repubblica Batava del 1797 (la Repubblica Batava era la repubblica sorella olandese della Repubblica Francese).

Ci furono poi altre due incursioni francesi nel 1798: “una seconda incursione – essendo la prima quella del generale Jean Humber a cui si fa riferimento sopra – accompagnata da Napper Tandy, naufragò sulla costa del Donegal; mentre Wolfe Tone[4] prese parte a una terza, sotto l’ammiraglio Jean-Baptiste-François Bompart, con il generale Jean Hardy al comando di una forza di circa 3.000 uomini.

Nel tentativo di mantenere breve questo articolo, non sono entrato troppo nei dettagli sul contesto storico; nelle note, potete trovare la narrazione dell’expédition d’Irlande e il concatenarsi degli eventi storici che hanno portato alla spedizione .

Alcuni punti interessanti però sono copiati di seguito (anche dal romanzo storico di Edward Rutherfurd “Ireland Awakening”):

1.l”expédition d’Irlande” del 1796: una volta completati i preparativi, la flotta francese salpò da Brest il 15 dicembre 1796 con circa 15.000 soldati su una varietà di navi di linea, fregate e grandi trasporti. Una volta in mare, il tempo non ha collaborato e le navi francesi sono state disperse da una tempesta[3]

2.Rutherfurd in “Ireland Awakening”[5] afferma che i risultati degli sforzi di Wolfe Tone in Francia erano stati piuttosto notevoli. Theobald Wolfe Tone, (nato il 20 giugno 1763, Dublino, Irlanda — morto il 19 novembre 1798, Dublino)[6], era un repubblicano irlandese, e nell’ottobre 1791 aiutò a fondare la Società degli Irlandesi Uniti, una società repubblicana determinata a porre fine al dominio britannico e ottenere un governo responsabile in Irlanda. Egli fu determinante nel realizzare l’expédition d’Irlande del 1796.

Rutherfurd afferma inoltre che Tone aveva davvero impressionato il Direttorio che governava la nuova repubblica rivoluzionaria. Tanto che avevano inviato non un contingente simbolico bensì una flotta di 43 navi, con a bordo 15.000 soldati. Altrettanto importante, dice, le navi trasportavano armi per 45.000 uomini. Soprattutto, erano sotto il comando del generale Hoche, che era il rivale dell’astro nascente della repubblica, Napoleone Bonaparte.

Louis Lazare Hoche; 24 giugno 1768 – 19 settembre 1797) è stato un capo militare francese delle guerre rivoluzionarie francesi[1]..

Rutherfurd premette ciò affermando che “la storia fornisce molti momenti intriganti- punti di svolta in cui, se non fosse stato per qualche condizione fortuita, il corso degli eventi futuri sarebbe potuto cambiare completamente. L’arrivo, il 22 dicembre 1796, della flotta francese in vista di Bantry Bay, all’estremità sud-occidentale dell’Irlanda, è uno di questi“[6]

In conclusione, ogni spedizione francese non è riuscita a raggiungere l’obiettivo di liberare l’Irlanda, ma i loro fallimenti erano dovuti più a tempi e condizioni meteorologiche sfavorevoli che alla superiorità della marina britannica.

La spedizione del generale Humbert nel 1798 fece sbarcare con successo le truppe francesi in Irlanda, diventando l’unica forza nemica a sbarcare truppe sulle isole britanniche nella storia moderna. Ha sconfitto gli inglesi nella battaglia di Castlebar, che divenne nota come le “Corse di Castlebar” a causa della velocità della ritirata britannica[7]. Contro ogni previsione, Humbert guidò la sua piccola forza attraversando mezza Irlanda prima di essere circondato e sconfitto da numeri britannici superiori. Se il Direttorio francese avesse agito prima e in concomitanza con la rivolta irlandese nel maggio del 1798, gli eventi sarebbero potuti andare diversamente. Negli anni successivi alla rivolta irlandese, Lord Cornwallis guidò le riforme per alleviare alcune delle cause alla base della ribellione irlandese del 1798, ma gli irlandesi avrebbero trascorso un altro secolo a lottare per l’indipendenza[3].

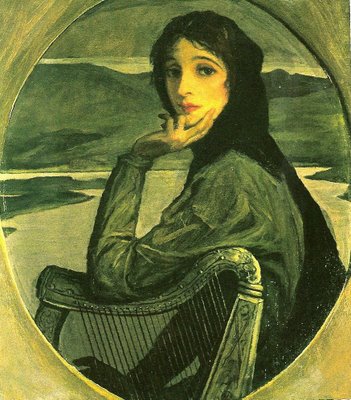

An tSeanbhean bhocht: Aisling song

The Wiki article “The Sean-Bhean bhocht”[8] provides a great introduction for this traditional Irish song:

“The Sean-Bhean bhocht” (pronounced [ˈʃanˠˌvʲanˠ ˈwɔxt̪ˠ]; Irish for “Poor old woman”), is often spelled phonetically as “Shan Van Vocht”.

The Sean-Bhean bhocht is used to personify Ireland, a poetic motif which heralds back to the aisling[9] of native Irish language poetry.

As an aside, Aisling also means dream or vision in Gaelige (the Irish language) and is a very popular Irish girl’s name!

L’articolo Wiki “The Sean-Bhean bhocht”[8] fornisce un’ottima introduzione a questo tradizionale irlandese:

“The Sean-Bhean bhocht” ( pronunciato [ˈʃanˠˌvʲanˠ ˈwɔxt̪ˠ] ; irlandese per “povera vecchia”), è spesso scritto foneticamente come “Shan Van Vocht”.

Sean-Bhean bhocht è la personificazione dell’Irlanda, un motivo poetico che preannuncia l’aisling[9] della poesia nella lingua nativa dell’Irlanda.

Per inciso, Aisling significa anche sogno o visione in Gaelige (la lingua irlandese) ed è un nome femminile molto popolare in Irlanda!

Many different versions of the song have been composed by balladeers over the years, with the lyrics adapted to reflect the political climate at the time of composition.

However, the title of the song, tune and narration of the misfortunes of the Shean Bhean bhocht remain a constant.

In Cúige Mumhan (the province of Munster), in ‘canúint na Mumhan’ (the Irish language dialect of Munster) – this is pronounced as ‘an tan van voct. ‘An tSeanbhean Bhocht’ has been anglicised to the ‘Sean-Bhean bhocht’ or to ‘the Shan Van Vocht’.

The song and lyrics express confidence in the victory of the United Irishmen in the looming rebellion upon the arrival of French aid.

Molte le versioni della canzone composte dai cantastorie nel corso degli anni, con i testi adattati per riflettere il clima politico al momento della composizione.

Tuttavia, il titolo della canzone, la melodia e la narrazione delle disgrazie della Shean Bhean bhocht rimangono una costante.

Nella parlata locale del Munster (‘canúint na Mumhan’) si pronuncia ‘an tan van voct.

“An tSeanbhean Bhocht” è stato anglicizzato in “Sean-Bhean bhocht” o in “Shan Van Vocht”.

La canzone e il testo esprimono fiducia nella vittoria degli United Irishmen nell’incombente ribellione all’arrivo degli aiuti francesi.

Lyrics and translations

The version in this article ‘as Gaelige’ is in the native Irish language. The song has a very popular English version also which is not covered here.

The translation provided below is my own, as I could not find any for the Gaelige version, so I’m more than happy to be notified of any errors or omissions, or improvements. Please note that the lyrics are not the same as the English version, which is probably more widely known in Ireland, which makes the Gaelige version very special in my opinion.

La versione del brano in questo articolo è nella lingua nativa irlandese. La canzone ha anche una versione inglese molto popolare che non è trattata qui.

La traduzione fornita di seguito è mia – non avendone trovate di già tradotte – sarei più che felice di essere informato di eventuali errori, omissioni o miglioramenti. Si prega di notare che i testi non sono gli stessi della versione inglese, che è probabilmente più conosciuta in Irlanda, il che rende la versione irlandese molto speciale secondo me.

Curfá

“Tá na Francaigh teacht thar sáile”

Arsa an tseanbhean bhocht.

“Tá na Francaigh teacht thar sáile,”

Arsa an tsean bhean bhocht.

“Táid ag teacht le soilse ré,

‘S beid anseo le fáinne an lae a,

‘S beidh ár namhaid go cráite tréith,”

Arsa an tsean bhean bhocht.

Véarsaí

“Is cá mbeidh cruinniú na Féinneb?”

Arsa an tseanbhean bhocht.

“Cá mbeidh cruinniú na Féinne?”

Arsa an tseanbhean bhocht.

“Thíos ar bhántaibh leathan réidhc,

Cois Chill Dara ghrámhar shéimhc,

Pící glana ‘s claimhte faobhair,d”

Arsa an tseanbhean bhocht.

“Is cén dath a bheidh in airde”

Arsa an tseanbhean bhocht

“Cad é an dath a bheidh in airde”

Arsa an tseanbhean bhocht.

Is ar bhrat uaine bhuacach arde

Gaoth dá scuabadh in uachtar barr

Is faobhar an óinseach duais le fáil ann

Arsa an tseanbhean bhocht.

“Is a bhfaighimid fós ár saoirse?”

Arsa an tseanbhean bhocht.

“An bhfaighimid fós ár saoirse?”

Arsa an tseanbhean bhocht.

“Beimid saor idir bhun is craobhf,

Beimid saor ó thaobh go taobhf,

Saor go deo le cabhair na naomh!”

Arsa an tseanbhean bhocht.

A small selection of ‘An tSeanbhean Bhocht’ videos

Muireann Nic Amhlaoibh

♪https://seannos.tg4.ie/baile/amhranaithe/meabh-n/an-tseanbhean-bhocht/

The song seems in canúint na Mumhan which seems appropriate as this is likely where it originated as the French were to land in Bantry Bay.

Aistriúchán – enghish translation

Chorus

The French are coming over the seas

Says the poor old woman

The French are coming over the seas

Says the poor old woman

They are coming with the light of the moon

And they will be here with the dawning of the day

And it will be our enemy that are tormented and weakened,

Says the poor old woman.

And where will it be, the Fenians meeting ?

Says the poor old woman

Where will it be, the meeting of the Fenians ?

Says the poor old woman.

Down below on the broad and wide, smooth and level grassy plains

Beside lovable, sweet Kildare

Clean pikes and sharp edged swords

Says the poor old woman.

And what colour will be the highest ?

Says the poor old woman

What colour will be highest ?

Says the poor old woman

It is on our banner of verdant green, proud, and tall

Wind rippling it at the very top

It’s the sharp edge of a sword the fool’s reward to find there

Says the poor old woman.

And will we receive yet our freedom ?

Says the poor old woman

Will we receive yet our freedom?

Says the poor old woman

We will be free between root and branchf

We will be free from side to sidef

Free forever with the help of the saints!

Says the poor old woman

Footnotes

a. “Le fáinne an lae” = “with the ring of the day” meaning the dawning of the day ie. dawn, due to the ring of light made at dawn as the sun rises

b. ‘Na Féinne’ or the ‘fenians’ are the legendary warrior bands of Fionn Mac Cumhaill

c. ‘Thíos ar bhántaibh leathan réidh ; Cois Chill Dara ghrámhar shéimh’ = Down below on the broad and wide, smooth and level grassy plains ; Beside lovable, sweet Kildare (this maybe the Curragh of Kildare referred to in the English version of the song)

d. ‘with their pikes in good repair’ according to the English version ; likely means with their pikes and sharp edged swords, or in general their weaponry, at the ready

e. ‘Is ar bhrat uaine bhuacach ard’ means a lofty, luxuriant, military banner ; uaine means it is a vivid, verdant, green ; maybe the emerald green of Ireland

f. “Beimid saor idir bhun is craobh ; Beimid saor ó thaobh go taobh” – “We will be free between root and branch ; we will be free from side to side” – This is maybe a metaphor for Ireland being free following a ‘root and branch’ change meaning every part of Ireland will be free, and from coast to coast as per the English version of the song. “Root and branch” is an idiom for complete change

La canzone è scritta nella parlata locale del Munster, il che sembra appropriato in quanto è probabile che essa abbia avuto origine quando i francesi sbarcarono a Bantry Bay.

traduzione italiana Cattia Salto

Coro

I francesi stanno arrivando oltremare

Dice la povera vecchia

I francesi stanno arrivando oltremare

Dice la povera vecchia

Stanno arrivando con la luce della luna

E saranno qui con l’alba del giorno

E sarà il nostro nemico ad essere tormentato e indebolito,

Dice la povera vecchia.

E dove sarà l’incontro dei feniani?

Dice la povera vecchia

Dove sarà l’incontro dei feniani?

Dice la povera vecchia.

In basso sulle pianure erbose ampie e larghe, piatte e pianeggianti

Accanto all’amabile, dolce Kildare

Picche pulite e spade affilate

Dice la povera vecchia.

E quale colore sarà innalzato?

Dice la povera vecchia

Quale colore sarà innalzato?

Dice la povera vecchia

È la nostra bandiera verdeggiante, orgogliosa e alta

Il vento la fa increspare in alto

È la lama affilata di una spada che lo stolto troverà li come ricompensa

Dice la povera vecchia.

E riavremo ancora la nostra libertà?

Dice la povera vecchia

Riavremo ancora la nostra libertà?

Dice la povera vecchia

Saremo liberi, rami e radici

Saremo liberi da sponda a sponda

Liberi per sempre con l’aiuto dei santi!

Dice la povera vecchia

Note

a.”Le fáinne an lae” = “con l’anello del giorno” che significa l’alba del giorno, a causa dell’anello di luce prodotto all’alba al sorgere del sole

b. ‘Na Féinne’ o ‘fenians’ sono le leggendarie bande di guerrieri di Fionn Mac Cumhaill

c. ‘Thíos ar bhántaibh leathan réidh; Cois Chill Dara ghrámhar shéimh’ = In basso sulle pianure erbose ampie e larghe, lisce e livellate; Accanto all’amabile, dolce Kildare (questo forse è il Curragh di Kildare a cui si fa riferimento nella versione inglese della canzone)

d. ‘con le loro picche in buono stato’ secondo la versione inglese; probabilmente significa con le loro picche e spade affilate, o in generale le loro armi, a portata di mano

e. ‘Is ar bhrat uaine bhuacach ard’ significa un’alta, lussureggiante bandiera militare; uaine significa che è un vivido, lussureggiante, verde; forse il verde smeraldo dell’Irlanda

f. “Beimid saor idir bhun is craobh ; Beimid saor ó thaobh go taobh” – “We will be free between root and branch; we will be free from side to side” – Questa è forse una metafora dell’Irlanda che è libera a seguito di un cambiamento ‘root and branch’ che significa che ogni parte dell’Irlanda sarà libera, e da costa a costa come da versione inglese della canzone. “Radice e ramo” è un modo di dire per un radicale cambiamento

References

[1]https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Exp%C3%A9dition_d%27Irlande_(1796)

https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spedizione_in_Irlanda_(1796)[2]https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Exp%C3%A9dition_d%27Irlande_(1798)

[3]https://www.frenchempire.net/articles/ireland/

[4]https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wolfe_Tone

[5]Ireland Awakening. Edward Rutherfurd. Published in the United Kingdon by Arrow Books in 2007. Copyright © Edward Rutherfurd 2006

[6]https://www.britannica.com/biography/Wolfe-Tone

[7]There is another interpretation of why this battle is called the “Races of Castlebar” that I found in a youtube comment to https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tE4g_HCZPaY and just repeating it here with huge thanks to the poster Aaron Conlon ‘@aaronconlon3880’: “The British force was made up of 6,000 troops with no combat experience and led by General Gerard Lake (an over confident leader) who set up defensive positions in the town of Castlebar. The Franco-Irish force was made up of 900 experienced French riflemen and 1,100 rebels armed with rifles taken from a captured British garrison and they were led by General Jean Humbert (a French General of Irish descent who won several battles in the Rhine campaign). Rebels had earlier captured the nearby town of Killala and Lake thought Humbert would attack Castlebar using the road from Killala so he focused his defences on that side of town. Instead most of the Franco-Irish force moved along Lough Conn and attacked from the other side of town. They quickly captured the British artillery and led a bayonet charge from behind that broke the British lines. This cleared the way for a Rebel cavalry charge from Killala that forced the British to flee the town and abandon the county all together. The cavalry charge was later nicknamed “the Castlebar races”.

[8]https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Sean-Bhean_bhocht

[9]https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aisling

https://terreceltiche.altervista.org/i-bardi-delle-terre-celtiche/#aisling