In the rural economy of the past milking the cows (as well as the preparation of butter and cheese) was a task performed by women. Thus the wisdom of the Celtic women has given rise to a whole series of work songs, which are also spells to ward off the evil eye and to calm the cows, so that the milk production is abundant and blessed. It is well known that goblins are fond of butter and milk, and folklore includes witches and disturbing animals like milk suckers with hostile intentions, or determined to make the milk sour, or to prevent the transformation of the cream into butter!

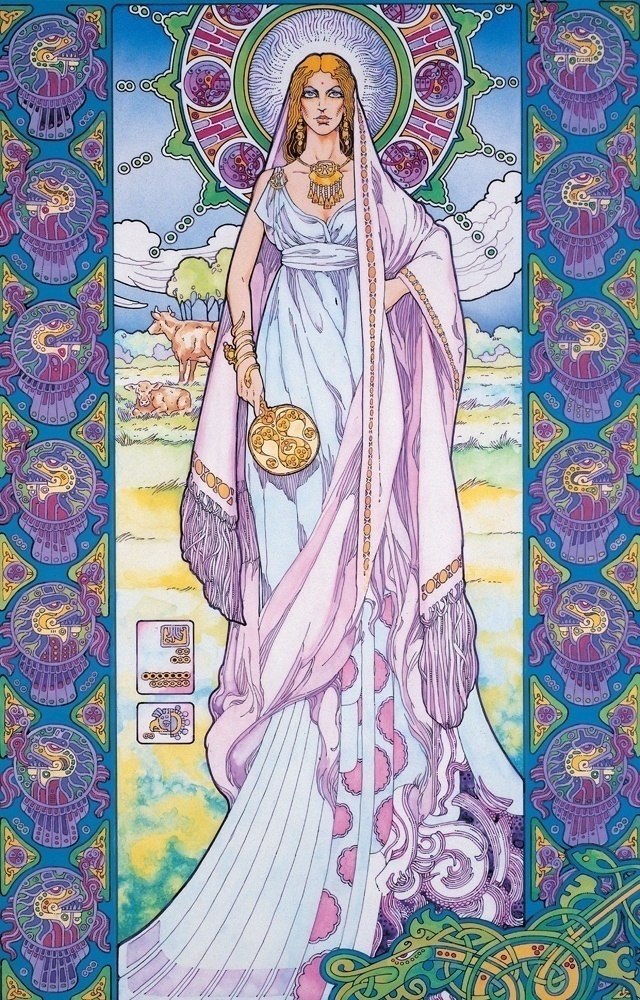

THE SYMBOLS OF THE GODDESS

A maiden milking a cow is a figure found carved on the walls of many medieval churches, and is a very old presence in the land of Ireland, or more generally along the coasts of Europe; in the pastures it is often found a “milking stone” cupped in which the women left offerings of milk to the gruagach, a spirit associated with a sacred cow coming from the sea. It could be the memory of ancient rituals celebrated by priestesses of the Mother Goddess which were transformed into fairy creatures.

In the megalithism there are names like The Cow and Calf attributed to particular rocks

The White Cow of Crichie,in the Buchan, has a name “frequently given to great stones, presumably, as this one, of white quartz”. The Cow and Calf Rocks loom near a dense cluster of carved rocks on Ilkley Moor, West Yorkshire. The Buwch a’r Llo – ‘Cow and Calf’ – are two standing stones by the road near Melindwr, Ceredigion, Wales. Such names may be the last trace of narratives associated with these configurations, evoking the belief that ‘the presence of her calf was essential when a cow was being milked and that a cow deprived of her calf would retain her milk’. L’ Épine Blanche (‘White Thorn’), the heroine of a Breton folktale, used a holly stick to strike a rock on the sea-shore, from which a cow emerged, to provide copious amounts of milk for the girl and her mother. One story, from Ireland, relates how a family on Dursey Island found a black bull and cow near the beach. The cow furnished sufficient butter and milk for all domestic wants, and soon a calf was added to the number. However, a wicked servant girl, milking the parent cow, struck the beast and cursed her. The animal turned to the other two and lowed to them, sorrowfully, and the three moved off to the sea. They plunged in, and forthwith the three rocks, since known as the Bull, Cow and Calf, arose. Milking legends’ surround megalithic structures such as Mitchell’s Fold stone circle in Staffordshire, where a witch milked a magical cow through a sieve, the cow thence ceasing to give her bounty of milk. During a famine, a benevolent white sea-cow provided milk at the Callanish stone circle on the Isle of Lewis, until a witch milked her through a sieve. The Glas Gowlawn (the Grey Cow), presented itself every day before each house in Ireland, giving a day’s supply of milk. So she continued until an avaricious person laid in a quantity for traffic, whereupon she left Ireland, going into the sea off the Hill of Howth. Y Fuwch Frech, ‘The Freckled Cow’, roamed the Mynydd Hiraethog near Ruthin. Her pasture was near a farm called Cefn Bannog (‘Horned Ridge’); she drank at the spring called Ffynnon y Fuwch Frech. A stone circle, Preseb y Fuwch Frech (‘The Freckled Cow’s Crib’) was her shelter. Whenever anyone went to her for milk, she filled the vessel with milk of the richest quality, and she never became dry. Eventually, a witch took a sieve and milked her dry. In response she walked to Llyn dau ychain, the Lake of the Two Oxen, in the parish of Cerrig-y-drudion, followed by her two children the Ychen Bannawg, the legendary long-horned oxen, bellowing as they went. They disappeared into the lake and were never seen again. In County Limerick, a cow emerged from the River Deel; if she were milked a hundred times a day she would each time fill a can. She departed into the river and was never more seen, when she was cursed by a woman milking her. This confluence of stone, water and animals in these narratives is a discernible element in a wide array of rock art traditions worldwide.” (from here)

Irish Goddess Boinn-Boann

In Ireland Boinn-Boann, the “White Cow” is the goddess who represents prosperity. The Cow or Bull ridden by Goddesses or by the Moon itself is the symbol of the power of Mother Earth, the force enclosed in the secret of Nature. Thus the cult of the ancient goddess is always transformed according to the new conceptions .. to remain always unchanged! (see more)

When the Celts worshiped cows, the “white cow” was a manifestation of the Goddess transmuted in the Boyne River, a small river in Ireland yet the cradle of prehistoric Celtic populations, who left the archaeological sites of Newgrange and Knowth in its valley. Nothing so cosmic as the Egyptian Mehetueret adored as the “Celestial Cow” or “The Great Heifer”, that is, the great celestial water, sometimes depicted as having a speckled body to simulate the starry sky. Between her horns the solar disk of Ra. Yet something quite similar.

Thus the Irish Boann is the lover of the Dagda and mother of Aengus. The myth tells that originally the river was the well of Segais, the well of wisdom, surrounded by Nine hazel trees and inhabited by a Salmon, which ate the sacred hazelnuts that fell into the water. The god-guardian of the magic well had forbidden his wife to come near, but she obviously disobeyed and released the energy of the well by walking around it counterclockwise. The waters released by the generous mother to fertilize the earth grew to become a river, and the goddess transmuted into it (the legend speaks of a punishment, death in the waters by dismemberment).

Crodh Chailein: Colin’s cattle

In the peasant world there existed a whole series of prayers and invocations, often in the form of songs, which were part of the cultural baggage dating back to the time of the Druids; these Ortha nan Gaidheal in Scottish Gaelic, come from the bardic tradition that survived in the folklore, through the centuries of Christianity and despite the English cultural hegemony, and were collected and translated at the end of 1800 by Alexander Carmichael (1832-1912), who published them in his book “Carmina Gadelica”.

The Church has often been wary of the songs of beautiful girls busy milking cows, considering at that as magical rituals or prayers to the ancient gods.

“Crodh Chailein” ( “Colin’s cattle”) is classified as a “milking song” and recorded on the field by Alan Lomax (South Uist) in the 1950s: it is a lullaby whispered to the cows to keep them quiet during milking, and to stimulate them magically in the production of a lot of milk.

Mary Cameron Mackellar writes in her essay ‘The Shieling: Its Traditions and Songs’ (Gaelic Society of Inverness 1889 from here) “Weird women of the fairy race were said to milk the deer on the mountain tops, charming them with songs composed to a fairy melody or “fonn-sith.” One of these songs is said to be the famous “Crodh Chailein.” I give the version I heard of it, and all the old people said the deer were the cows referred to as giving their milk so freely under the spell of enchantment. .. Highland cows are considered to have more character than the Lowland breeds, and when they get irritated or disappointed, they retain their milk for days. This sweet melody sung – not by a stranger, but by the loving lips of her usual milkmaid – often soothes her into yielding her precious addition to the family supply.”

Scottish cows are so used to this treatment that they do not give milk without a song !!

Ethel Bassin in her “The Old Songs of Skye: Frances Tolmie and her Circle” (1997) shows two verses of the song collected by Isabel Cameron of the Isle of Mull (internal Hebrides) along with the legend of its origin reported by Niall MacLeòid , “the Skye bard.”

Who sings is the woman kidnapped by the fairies on her wedding day and yet she gets permission to go every day to milk the cows of her husband named Colin: the husband can hear her singing but he can not see her. The bard assures us that the woman will return after one year and a day to her human husband! The abduction of the bride on wedding day was not so remote a possibility according to the beliefs of the time and there were many tricks to keep the fairies away in that occasion! (see more).

According to another legend, Colin’s wife dies at a young age and comes back a few months after her burial for the evening milking of the cows singing this song.

The melody (see) also called Crochallan is also known as My Heart’s In The Highlands . The oldest version in print (text and score) is in “The Elizabeth Ross Manuscript” (1812)

Mary Mackellar lyrics

Seist (chorus)

Chrodh Chailein, mo chridhe, Crodh Iain, mo ghaoil,

Gun tugadh crodh Chailein, Am bainn’ air an fhraoch.

I

Gun chuman, gun bhuarach, Gun lao’-cionn, gun laogh,

Gun ni air an domhan, Ach monadh fodh fhraoch.

II

Crodh riabhach breac ballach, Air dhath nan cearc-fraoicb,

Crodh ‘lionadh nan gogan ‘S a thogail nan laogh.

III

Fo ‘n dluth-bharrach uaine, ‘S mu fhuarain an raoin,

Gun tugadh crodh Chailein Dhomh ‘m bainn’ air an fhraoch.

IV

Crodh Chailein, mo chridhe, ‘S crodh Iain, mo ghaoil,

Gu h-uallach ‘s an eadar-thrath, A beadradh ri ‘n laoigh

Listen these three milking songs in sequence:: “Crodh Chailein”, “Chiùinan Ghràidh” e “a’ Bhanarach Chiùin”

Donald Sinclair from Tiree 1968 ♪

Scots Gaelic (from here)

Crodh Chailein mo chridhe Crodh chailein mo ghaoil

Gu’n tugadh crodh Chailein Dhomh bainn’ air an fhraoch

Gu’n tugadh crodh Chailein Dhomh bainn’ air an raon

Gun chuman(1), gun bhuarach Gun luaircean(2), gun laugh.

Gu’n tugadh crodh Chailein Dhomh bainne gu leoir

Air mullach a’ mhonaidh Gun duine ‘nar coir

Gu bheil sac air mo chridhe ’S tric snidh air mo ghruaidh

agus smuairean air m’aligne Chum an cadal so bhuam

Cha chaidil, cha chaidil cha chaidil mi uair

cha chaidil mi idir gus an tig na bheil uam.

1) cogue = wooden vessel used for milking cows

2) luaircean = a substitute calf, an inanimate prop over which the skin of a milk cow’s deceased calf was draped, in order to console her with it’s scent, thus encouraging her to continue to produce milk

The cattle of Colin my dearest, The cattle of Colin my love,

Colin’s cattle would give me milk Upon the heather

Colin’s cattle would give me milk Upon the field,

without a cogue(1), a shackle, a luaircean(2), without a calf.

Colin’s cattle would give plenty of milk to me,

on top of the moor without anyone near us.

There is a weigh on my dart, and often tears on my cheek,

And sorrow on my mind That has kept sleep from me.

I will not sleep, I will not sleep, I will not sleep an hour,

I will not sleep at all until what I long for returns.

English translation Charles Stewart*

I

I won’t sleep, I won’t sleep I won’t sleep one hour,

I won’t sleep at all Until what was taken returns.

II

May Colin’s cattle give me Milk for their love of me,

At the top of the hill With no one nearby.

Chorus

Cows of my beloved Colin Iain’s cows, my dear; Cows that

would fill up the milking bucket, Cows that rear the calves

III

My heart is heavy, Tears frequently on my cheeks,

My mind is dejected, And this stops me sleeping.

IV

I won’t go to the birch wood Or gathering nuts;

On a brown, ragged plaid I wait for the cows.

* in “The Killin Collection of Gaelic Songs”

Scots Gaelic (from here)

I

Cha chaidil, cha chaidil, Cha chaidil mi uair,

Cha chaidil mi idir Gus an tig na bheil bhuam.

II

Gun toireadh crodh Chailein, Dhomh bainn’ air mo ghaol,

Air mullach a’ mhonaidh, Gun duine nar taobh.

Seist (chorus)

Crodh Chailein mo chridhe, Crodh Iain, mo ghaoil;

Crodh lìonadh nan gogan, Crodh togail nan laogh.

III

Gu bheil sac air mo chridhe, ’S tric snigh’ air mo ghruaidh,

Agus smuairean air m’ aigne, Chùm an cadal seo bhuam.

IV

Cha tèid mi don bheithe, No thional nan crò;

Air breacan donn ribeach Tha mi feitheamh nam bò.

SOURCE

http://www.skyelit.co.uk/poetry/collect21.html

http://www.lochiel.net/archives/arch116.html

http://scotsgaelicsong.wordpress.com/2014/03/18/scots-gaelic-song-crodh-chailein/ http://plover.net/~agarvin/faerie/Text/Music/54.html

http://www.tobarandualchais.co.uk/en/fullrecord/57427/8;jsessionid=97E1C046ADC0124A757755FF5E401B2F

https://thesession.org/tunes/11647