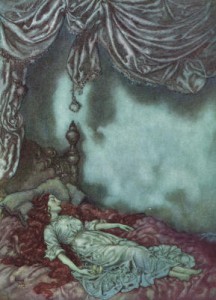

Nella tradizione popolare sono molto numerose le ballate dette “night-visiting” in cui l’amante bussa alla finestra della fidanzata e viene fatto entrare nella camera da letto nottetempo. Alcune di esse aggiungono un tocco “macabro” trattandosi della visita di un revenant ossia di un fantasma fin troppo in carne!!

In “Fair Margaret and Sweet William” è la bella Margaret che appare a William (presumibilmente in sogno) e lo “tormenta”. In “Sweet William’s Ghost” il fantasma è William che legato a Margaret da una promessa matrimoniale, non può riposare in pace fino a quando lei non lo scioglierà dal vincolo.

[English translation]

In the popular tradition there are a lot of ballads called “night-visiting song” in which the lover knocks at the window of the fiancée and is let into the bedroom at night. Some of them add a “macabre” touch since it is a visit to a revenant, that is to say a ghost in flesh and blood!

In “Fair Margaret and Sweet William” (Child # 74) it is the beautiful Margaret who appears to William (presumably in a dream) and “torments” him. In “Sweet William’s Ghost” the ghost of William, tied to Margaret by a marriage vow, cannot rest in peace until she unties him.

THE GREY COCK

La ballata è riportata dal professor Child come #248 in una sola versione settecentesca (Ancient and Modern Scots Songs, Herd, 1769), ma nella tradizione popolare sia in Inghilterra che in America si ritrovano quasi un centinaio di testi.

La prima registrazione di “The Grey Cock” è quella del 1951 dalla voce di Cecilia Costello (nata Kelly, 1884–1976), di famiglia irlandese emigrata in Inghilterra per sfuggire alla Grande Carestia, così Rod Stradling commenta nel libretto allegato a “Old Fashioned Songs”: “Questa ballata è variamente chiamata The Lover’s Ghost, Willie’s Ghost e The Grey Cock. La signora Costello sembrava preferire l’ultima, che a volte abbreviava con The Cock. È forse la classica “revenant ballad”, con quasi tutti i motivi che di solito si trovano in queste canzoni. Come la maggior parte dei telespettatori di oggi sapranno, “Les Revenants” sono “The Returned” [i Redivivi] quindi le “revenant ballad” trattano delle visite spettrali degli amanti morti. Possono essere abbastanza difficili da separare dalle ‘night visiting songs’ [“canzoni in visita notturna”], che di solito hanno una trama molto simile, ad eccezione del verso “I am but the ghost of your Willie-O”; dopo di che Willie e Mary consumano il loro amore presente – piuttosto che parlare del loro passato – fino a quando il gallo canta.

La ballata circolava in Inghilterra già nel diciassettesimo secolo, ma nessuna versione più bella di quella di Mrs Costello è stata raccolta. Lei credeva che l’amante spettrale fosse un soldato e che la visita all’innamorata avvenisse mentre il suo corpo giaceva mortalmente ferito sul campo di battaglia. Il richiamo del gallo al fantasma per esortarlo a ritornare indicava che la morte del soldato era imminente. Poiché le “revenant ballad” sono abbastanza comuni, è piuttosto sorprendente scoprire che questa ha solo 74 registrazioni Roud, sebbene sia stata sentita in Gran Bretagna e in Nord America. Ci sono state 25 registrazioni sonore, circa la metà delle quali sono state pubblicate in un dato momento, Purtroppo, solo quelle di: Maggie Murphy (MTCD329-0); Vergie Wallin (MTCD503-4); Bill Cassidy (MTCD325-6); Ellen Mitchell (MTCD315-6); Roisin White (VT126CD); e Duncan Williamson, nel CD che accompagna il libro Traveller’s Joy (EFDSS, 2006) sono state trasferite su Cd”

The ballad is reported by Professor Child as # 248 in only one eighteenth-century version (Ancient and Modern Scots Songs, Herd, 1769), but in the popular tradition both in England and in America almost a hundred texts are found.

The first recording of “The Gray Cock” is that of 1951 from the voice of Cecilia Costello (born Kelly, 1884–1976), of an Irish family emigrated to England to escape the Great Famine, so Rod Stradling comments in the booklet attached to “Old Fashioned Songs “: (MTCD363-4) : “This ballad is variously called The Lover’s Ghost, Willie’s Ghost and The Grey Cock. Mrs Costello seemed to prefer the last, which she sometimes abbreviated to The

Cock. It is perhaps the classic ‘revenant ballad’, having almost all the motifs usually

found in such songs. As most of today’s TV viewers will know, ‘Les Revenants’ are ‘The Returned’, so ‘revenant ballads’ deal with ghostly visitations from dead lovers. They can be quite difficult to separate from ‘night visiting songs’, which usually have a very similar plot, except for the “I am but the ghost of your Willie-O” line; after which Willie and Mary consummate their present love – rather than talk of their past one – and part when the cock crows.

The ballad was circulating in England as early as the seventeenth century, but no version finer than Mrs Costello’s has been collected. She believed that the ghostly lover was a soldier, and that the visit to his lover took place while his body lay mortally wounded on the battlefield. The cock’s summons to the ghost to return indicated that the death of the soldier was about to take place. Since revenant ballads’ are fairly common, it’s quite a surprise to find that this one has only 74 Roud entries, although it has been heard all over these islands and North America. There have been 25 sound recordings, about half of which have been published at some time. Sadly, only those by: Maggie Murphy (MTCD329-0);Vergie Wallin (MTCD503-4); Bill Cassidy (MTCD325-6); Ellen Mitchell (MTCD315- 6); Roisin White (VT126CD); and Duncan Williamson, on the CD accompanying the book Traveller’s Joy (EFDSS, 2006) have made the transition to the CD medium.“

DAWN SONG OR REVENANT BALLAD?

Apro una parentesi che in altri contesti è argomento di accesa discussione: la ballata è una Dawn Song oppure una Revenant Ballad? Alcuni studiosi vedono nella versione di Cecilia Costello la testimonianza di uno stadio più antico della storia, ossia una storia di fantasmi che nel settecento ha perso il suo carattere soprannaturale per diventare una “dawn song” ossia una “night-visiting” song. Altri invece argomentano che la ballata è sempre stata una “dawn song”, e che piuttosto sia stato il gusto ottocentesco per il macabro, ad aver aggiunto il particolare più morboso dell’appuntamento con il “fantasma”. Così Hugh Shields nel suo saggio “The Grey Cock: Dawn Song or Revenant Ballad?” conclude che la forma più antica della ballata è quella che si rifà al genere della poesia cortese medievale ovvero alla lirica trobadorica e troviera nella particolare forma dell’aubade (Il canto dell’alba).

I open a parenthesis that in other contexts is a topic of heated discussion: is the ballad a Dawn Song or a Revenant Ballad? Some scholars see in the version of Cecilia Costello the testimony of a more ancient stage of history, that is a ghost’s story that in the eighteenth century lost its supernatural character to become a “dawn song” or a “night-visiting” song. Others argue that the ballad has always been a “dawn song”, and it was the nineteenth-century gotic taste for the macabre, to have added the most morbid detail of the meeting with the “ghost” . So Hugh Shields in his essay “The Gray Cock: Dawn Song or Revenant Ballad?” concludes that the most ancient form of the ballad is about the genre of courtly medieval poetry (the troubadour lyric) in the particular form of the aubade (The song of the dawn)

LA VERSIONE INGLESE

La versione della signora Costello è riportata in “The Peguin Book of English Folk Songs” di Ralph Vaughan Williams & A. L. Lloyd.

Mrs. Costello’s version is featured on “The Penguin Book of English Folk Songs” by Ralph Vaughan Williams & A. L. Lloyd.

I

“I must be going, no longer staying,

the burning Thames(1) I have to cross.

I must be guided without a stumble(2)

into the arms of my dear lass.”

II

When he came to his true love’s window,

he knelt down gently on a stone,

and it’s through a pane he whispered slowly,

“my dear girl, do you alone?”

III

She’s rose her head from her down-soft pillow,

and snowy were her milk-white breasts,

saying:”who’s there, who’s there at my bedroom window,

disturbing me from my long night’s rest?(3)”

IV

“oh, I’m your love and don’t discover,

I pray you rise love and let me in,

for I am fatigued from my long night’s journey,

besides, I am wet into the skin(4).”

V

Now this young girl rose and put on her clothing,/so quickly let her true love in.

oh, they kissed, shook hands,

and embraced each other

till that long night was near an end.

VI

“willy dear, oh dearest willy,

where is that colour you’d some time ago?”

“o mary dear, the clay has changed me

and I’m but the ghost of your willy, oh.”

VII

“Then oh cock, oh cock, oh handsome cockerel,

I pray you not crow until it is day(5),

for your wings I’ll make of the very first beaten gold,

and your comb I’ll make of the silver grey.”

VIII

But the cock it crew, and it crew so fully,

it crew three hours before it was day,

and before it was day, my love had to leave me,

not by light of the moon or light of the sun(6).

IX

then it’s “willy dear, oh dearest willy,

when ever shall I see you again?”

“when the fishes fly, love, and the sea runs dry, love,

and the rocks they melt in the heat of the sun”

FOONOTES

1) I think it refers to the lighting of the sunset in the waters of the river that take on the reddish color of the sky, but it is also symbolising the difficulty of the dead returning

2) those who come to visit from the Other Celtic World (where they lived according to the passage of time enchanted – one day at Fairy corresponds to a terrestrial year) not they must rest their feet on the ground because otherwise they are reached by the earth age

3) Winter Solstice night

5) the girl by no means impressed by the news that her fiancé is a revenant, begs the cock not to sing too soon and offers him offers in gold and silver. So some want to see in this cock a mythical bird guardian of the doors of the Otherworld (here); it is a psychopomp animal that is a guide of the souls of the dead: the rooster is already in itself a strongly symbolic animal, and the phrase is he explains without having to resort to a mythical and unspecified guardian bird of the world of the dead. The rooster sings foretelling the rising of the sun, whose light dissolves the terror of darkness: therefore for the transitive property the crowing of the cock assumes the power to make the creatures of the night vanish, nightmares and ghosts. The whole verse is preserved in the nursery rhyme Cock-a-doodle-doo Oh, my pretty cock, oh, my handsome cock, I pray you, do not crow before day, And your comb shall be made of the very beaten gold, And your wings of the silver so gray. (The Annotated Mother Goose, William Stuart e Lucile Baring-Gould 1958)

6) the dawn is that indefinite moment in which it is no longer night but it is not even day; the junction point of the two worlds is an indeterminate point so it is a threshold that allows one to pass from one world to another

7) impossible riddles

Traduzione italiana di Cattia Salto

I

“Devo andare, non resterò a lungo,

il Tamigi in fiamme devo attraversare.

Sarò guidato senza passi falsi

tra le braccia della mia amata ragazza”

II

Quando venne alla finestra del suo vero amore,

si inginocchiò piano sulla pietra

e attraverso il vetro sussurrò piano

“Mia cara ragazza, sei sola?”

III

Lei alzò la testa dal soffice cuscino

e nivei e bianco-latte erano i suoi seni

dicendo ” Chi c’è, chi c’è alla finestra della mia stanza/che disturba il mio riposo in questa lunga notte?”

IV

“Oh sono il tuo innamorato, non mi smascherare, ti prego amore alzati e fammi entrare,

perchè sono stanco del mio viaggio in questa lunga notte

inoltre sono bagnato fino al midollo”.

V

Allora la giovane ragazza si alzò e si vestì

e lestamente fece entrare il suo amore.

Oh si baciarono, si strinsero le mani

e si abbracciarono

finchè quella lunga notte stava per finire.

VI

“Caro Willy, oh amato Willy,

dov’è il colorito che avevi fino a poco tempo fa?”

“Oh cara Mary la terra mi ha cambiato

e oh non sono che il fantasma del tuo Willy!”

VII

“Allora gallo o gallo o bel galletto

ti prego di non cantare fino a che è giorno

perchè le tue ali ricoprirò di oro zecchino

e la tua cresta ricoprirò d’argento”

VIII

Ma il gallo cantò e cantò forte,

tre ore prima del giorno,

e prima che fosse giorno il mio amore mi dovette lasciare, né sotto la luce della luna, né sotto la luce del sole.

IX

“Willy caro Willy,

quando ti rivedrò ancora?”

“Quando i pesci voleranno, amore e il mare si prosciugherà, amore e le rocce si fonderanno al calore del sole!”

NOTE

1) credo si riferisca all’accendersi del tramonto nelle acque del fiume che prendono il colore rossastro del cielo, ma potrebbe anche rappresentare la difficoltà per un defunto di ritornare nel mondo dei vivi

2) “Senza posare piede” sono espressioni che stanno a indicare una vecchia credenza popolare: coloro che vengono in visita dall’Altro Mondo Celtico (dove hanno vissuto secondo lo scorrere del tempo fatato – un giorno presso Fairy corrisponde ad un anno terrestre) non devono posare i piedi sul suolo perchè altrimenti vengono raggiunti dall’età terrestre

3) Winter Solstice night

la lunga notte è molto probabilmente quella del Solstizio d’Inverno

4) ho tradotto l’espressione secondo l’equivalente frase idiomatica in italiano: William è bagnato perchè presumibilmente è morto annegato

5) la fanciulla per niente impressionata dalla notizia che il suo fidanzato è un revenant, prega il gallo di non cantare troppo presto e gli porge delle offerte in oro e argento. Così alcuni voglio vedere in questo gallo un mitico uccello guardiano delle porte dell’Altromondo (qui), ma semmai è un animale psicopompo cioè una guida delle anime dei defunti : il gallo è già di per sé un animale fortemente simbolico, e la frase si spiega senza dover ricorrere a un mitico quanto imprecisato uccello guardiano del mondo dei morti. Il gallo canta preannunciando il sorgere del sole, la cui luce dissolve il terrore delle tenebre: perciò per la proprietà transitiva il canto del gallo assume il potere di far svanire le creature della notte, gli incubi e i fantasmi. Tutta la strofa è conservata nella nursery rhyme Cock-a-doodle-doo (in italiano Chicchirichì)

6) l’alba è quel momento indefinito in cui non è più notte ma non è nemmeno giorno; il punto di congiunzione dei due mondi è un punto indeterminato così è una soglia che permette di passare da un mondo all’altro

7)situazioni paradossali che fanno parte di una lunga tradizione sulle imprese impossibili

LOVER’S GHOST la versione irlandese

La versione proviene da Patrick W. Joyce che la imparò da ragazzo nel 1830 circa nella sua nativa Glenosheen, Contea di Limerick e che pubblicò nel suo “Old Irish Folk Music and Songs” (1909). Qui il revenant è la donna.

The version is that learned by P.W. Joyce as a child in Glenosheen, County Limerick and published in his Old Irish Folk Music and Songs (1909).

Here the revenant is the woman

I

“You’re welcome home again,” said the young man to his love,/“I’ve been waiting for you many a night and day./ You’re tired and you’re pale,” said the young man to his dear,

“You shall never again go away.”

II

“I must go away,” she said, “when the little cock do crow/ For here they will not let me stay.

Oh but if I had my wish, oh my dearest dear,” she said,

“This night should be never, never day.”

III

“Oh pretty little cock, oh you handsome little cock,/I pray you do not crow before day/ And your wings shall be made of the very beaten gold/And your beak of the silver so grey“

IV

But oh this little cock, this handsome little cock,

It crew out a full hour too soon./“It’s time I should depart, oh my dearest dear,“ she said,/“For it’s now the going down of the moon“

V (1)

“And where is your bed, my dearest love,“ he said,/“And where are your white Holland sheets?/And where are the maids, oh my darling dear,” he said,

“That wait upon you whilst you are asleep?”

VI

“The clay it is my bed, my dearest dear,” she said,

“The shroud is my white Holland sheet.

And the worms and creeping things(2) are my servants, dear,” she said,

“That wait upon me whilst I am asleep.”

Traduzione italiana di Cattia Salto

I

“Benvenuta nuovamente a casa”- disse il giovane al suo amore

“ti ho aspettata notte e giorno.

Sei stanca e pallida” disse il giovane alla sua cara

“non dovrai mai più andare via”

II

“Devo andare – disse lei– quando il galletto canta

perchè qui non si può restare.

Oh se dipendesse dalla mia volontà, mio

amore caro – disse lei –

questa notte non avrebbe mai, mai un giorno”

III

“Oh galletto, oh tu bel galletto

ti prego di non cantare prima che faccia giorno

e le tue ali ricoprirò di oro zecchino

e la tua cresta dell’argento più chiaro”

IV

Ma quel galletto, quel bel galletto

cantò prima di un’intera ora.

“E’ l’ora della partenza mio caro amore – disse lei – perchè è ora che tramonta la luna “

V

“E dov’è il tuo letto, mio caro amore – disse lui –

dove sono le tue bianche lenzuola di fiandra?

E dove sono le ancelle oh mio

caro amore – disse lui –

che vegliano sul tuo sonno mentre dormi?”

VI

“La terra è il mio letto, mio caro

amore – disse lei –

il sudario è il mio lenzuolo di Fiandra

e i vermi e le serpi sono le miei servitori, amore –

disse lei –

che vegliano su di me mentre dormo”

NOTE

1) the verses recalls the funeral of the sea already present in the wauking songs of the Hebrides (see Ailein Duinn)

la struttura dei versi richiama il funerale del mare già presente nelle wauking songs delle isole Ebridi (vedasi Ailein Duinn)

2) in the Bible verses

l’espressione è biblica

LA VERSIONE DI TERRANOVA

In questa versione si evince chiaramente che la donna è rimasta ad attendere il suo innamorato per lungo tempo mentre lui è morto in mare. In una non precisata notte Johnny ritorna a casa e bussa alla finestra della fidanzata perchè si svegli e lo faccia entrare nella camera.

Le note di copertina recitano “Questa è una revenant ballad di Terranova, raccolta da Maud Karpeles nel 1929 e pubblicata nelle sue Folk Songs from Newfoundland (1971). La versione viene dal canto di Alison McMorland e Kirsty Potts registrato al Fife Traditional Singing Weekend, maggio 2004. Nel Volume 2 di Tim Neat di recente pubblicazione Hamish Henderson: una biografia, Alison ricorda che era stata data a Henderson, una registrazione della canzone cantata da un cantante sconosciuto di Salford, vicino a Manchester, in Inghilterra.”

In this version it is clear that the woman has been waiting for her lover for a long time while he is died at sea. In an unspecified night Johnny returns home and knocks on his lover’s window so she wakes up and lets him enter the room.

“This is a revenant ballad from Newfoundland. It was collected by Maud Karpeles in 1929 and published in her Folk Songs from Newfoundland (1971). This version is from the singing of Alison McMorland and Kirsty Potts, recorded at the Fife Traditional Singing Weekend, May 2004. In Volume 2 of Tim Neat’s recently published Hamish Henderson: A Biography, Alison recalls being given, by Henderson, a recording of the song as sung by an unknown singer from Salford, near Manchester, England.”

I

“Johnny he promised to marry me,

But I fear he’s with some fair one gone.

There’s something bewails him

and I don’t know what it is,

And I’m weary of lying alone.”

II

Johnny come here at the appointed hour,

And he’s knocked on her window so low.

This fair maid arose

and she’s hurried on her clothes

And she’s welcomed her true lover home.

III

She took him by the hand

and she laid him down,

She felt he was cold as the clay.

“My dearest dear, if I only had one wish

This long night would never turn to day.

IV(1)

Crow up, crow up you little bird

And don’t you crow before the break of day,

And you’ll keep shielding made of the glittering gold

And that doors of the silvery gray.”

V

“And where is your soft bed of down, my love?

And where is your white Holland sheet?

And where is the fair girl who watches over you

As you taking your long, sightless sleep?”

VI

“The sand is my soft bed of down, my love,

The sea is my white Holland sheet.

And the long, hungry worms will feed off of me

As I lie every night in the deep.“

VII

“Oh, when will I see you again, my love?”

“Oh, when will I see you again?”

“When the little fishes fly and the seas they do run dry

And the hard rocks they melt in the sun.”

FOOTNOTES

1) this verse is generally referred to a cock

Traduzione italiana di Cattia Salto

I

“Johnny promise di sposarmi

ma temo sia andato con un’altra bella.

C’è qualcosa che lo tormenta

ma non so cosa sia

e sono stanca di stare sola.”

II

Johnny arrivò all’ora convenuta

e bussò alla finestra piano piano.

La bella fanciulla si alzò

e si vestì in fretta

per accogliere il ritorno a casa del suo amore.

III

Lo prese per mano e

si distese al suo fianco

e sentì che era freddo come la terra “Amore mio caro,

se solo avessi un desiderio da esprimere,

questa lunga notte non avrebbe mai un giorno.

IV

Taci, taci tu uccellino

e non cantare prima dello spuntare del giorno

e otterrai sbarre fatte d’oro zecchino

e porte d’argento.

V

Dov’è il tuo soffice letto di piume, amore mio,

dove sono le tue bianche lenzuola di Fiandra?

E dov’è la bella ragazza che veglia su di te

mentre tu prendi il tuo lungo sonno?“

VI

“La sabbia è il mio soffice letto dei fondali, cara

il mare è il mio lenzuolo di Fiandra

e i lunghi e affamati vermi si nutriranno di me mentre giaccio ogni notte negli abissi“

VII

” Quando ti rivedrò ancora, amore mio?

Quando ti rivedrò ancora?“

“Quando le aringhe voleranno, e il mare si prosciugherà

e le rocce si fonderanno al sole!“

NOTE

1) questa strofa è quella in genere riferita gallo anche se qui diventa un “little bird”: l’uccellino è tenuto nella gabbietta da qui la promessa di oro e argento per le sbarre e la porticina (shielding= cage)

Links

http://ontanomagico.altervista.org/suffolk-miracle.htm

http://mainlynorfolk.info/lloyd/songs/thegreycock.html http://mainlynorfolk.info/lloyd/songs/theloversghost.html http://saturdaychorale.com/2013/04/15/ralph-vaughan-williams-1872-1958-the-lovers-ghost-by-vaughan-williams-lumina-vocal-ensemble/ http://www.8notes.com/scores/4737.asp?ftype=gif http://www.joe-offer.com/folkinfo/songs/7.html http://www.mudcat.org/thread.cfm?threadid=79144 http://www.mudcat.org/thread.cfm?threadid=1659 http://www.fresnostate.edu/folklore/ballads/C248.html http://www.cavernacosmica.com/simbologia-del-gallo/