Paddy On The Railway è una sea shanty e anche una popolare canzone folk irlandese-americana di denuncia sociale con un humor caustico tipicamente irish. I testi variano molto con varianti diffuse oltremare da tutta la diaspora irlandese della metà Ottocento.

[English translation]

Paddy On The Railway is a sea shanty and a popular irish-american folk song, which is also a political song of social denunciation, with a typically Irish caustic humor.

The lyrics vary widely, with versions scattered all across the mid-19th century Irish diaspora.

AMERICAN RAILWAY

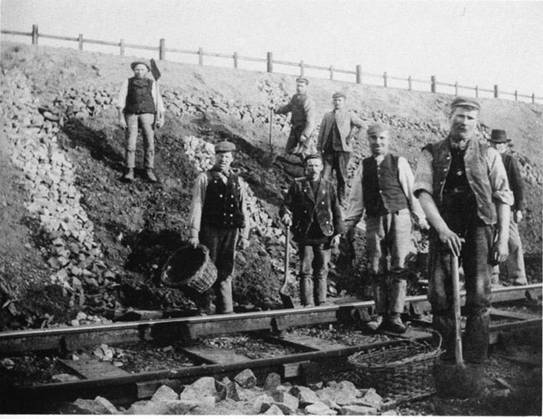

Una sorte infame quella degli immigrati irlandesi (e italiani) che lavoravano nella costruzione della ferrovia americana: gente che aveva come sola risorsa la forza delle braccia, ancora più infame per i milioni di lavoratori cinesi, spesso cooptati forzosamente e trattati in modo disumano, reietti e disprezzati più dei neri stessi (consiglio di leggere “Il cinese” dello svedese Mankell Henning che è si un thriller, ma nella trama storica si riallaccia a vicende iniziate proprio negli stessi anni della nostra canzone durante la costruzione delle ferrovie americane)

An infamous fate that of the Irish (and Italian) immigrants who worked in the construction of the American railway: people who had as their sole resource the strength of their arms; even more infamous for the millions of Chinese workers, often forced (shanghaiinge) and treated inhumanly, rejected and despised more than the blacks themselves (I recommend reading “The Chinese” by the Swedish Mankell Henning which is a thriller, but in the historical plot he outlined events that began in the same years of our song about the construction of the American railways).

I NUOVI SCHIAVI

Gli uomini vivevano in baracche o tendopoli rigorosamente suddivise per etnie e costruite man mano lungo la linea ferroviaria, costretti quasi all’isolamento, vessati da capi e capetti che facevano la cresta sui pasti e sulle forniture. Dalla paga infatti si dovevano detrarre il costo del pernottamento e del cibo, nonché dei pochi extra che potevano permettersi (spesi per lo più nel bere, ma anche per il gioco d’azzardo e le donnine). Così nonostante la paga fosse alta rispetto ad esempio a quella dei lavoratori delle fabbriche, spesso a fine stagione il manovale era indebitato con la compagnia e doveva restare ancora per l’anno successivo. Questo lavoro perciò finiva per abbrutire un uomo, sfinito dalla fatica e incupito da una vita priva d’affetti e di prospettive.

I lavoratori morivano a migliaia oltre che per gli incidenti sul lavoro (compresi gli assalti degli Indiani), anche per le precarie condizioni igienico-sanitarie, colpiti dalle malattie genericamente indicate come febbri (colera, vaiolo, dissenteria, tifo) e sepolti in tombe senza nome lungo la pista.

The men lived in barracks or tents strictly divided by ethnic group and built along the railway line, almost to isolation, harassed by chiefs who skimming from meals and supplies. In fact, the cost of accommodation and food had to be deducted from the pay, as well as the few extras they could afford (mostly spent on drinking, but also for gambling and women). Even though the pay was high, for example compared to that of factory workers , often at the end of the season the laborer was in debt with the company and had to remain working for the following year. This work therefore ended up brutalizing a man, exhausted by fatigue and darkened by a life devoid of affection and prospects.

Workers died by the thousands as well as from work-related accidents (including the assaults of the Indians), and due to the precarious hygienic-sanitary conditions, affected by the diseases generically referred to as fevers (cholera, smallpox, dysentery, typhus) and buried in tombs without name along the track.

Il Cimitero di Funk

Nel cimitero di Funk, Illinois vennero sepolti una cinquantina di lavoratori irlandesi deceduti negli anni 1850 mentre lavoravano alla costruzione della Chicago & Alton Railroad; nel 2000 presso la fossa comune è stata retta una croce celtica con la seguente iscrizione “Questa croce celtica onora la memoria di più di 50 anime qui sepolte mel 1853. I loro nomi sono noti solo a Dio. Questi immigranti dall’Irlanda sono stati cacciati dalla loro casa dalla carestia, giacendo sepolti qui nell’anonimato, lontani dalle vecchie amate case, ma per sempre a un passo dalle nuove case delle loro speranze. Sono arrivati malati e senza un soldo, e hanno preso lavori duri e pericolosi per costruire la Chicago & Alton Railroad. I loro sacrifici hanno permesso di sviluppare le ricchezze della terra di cui godiamo oggi. “

Un quadro dettagliato qui

Fifty Irish workers who died in the 1850s while working on the Chicago & Alton Railroad were buried in the Funk cemetery in Illinois; in 2000 a Celtic cross with the following inscription was held at the mass grave: “This Celtic cross honors the memory of more than 50 souls buried here about 1853. Their names are known but to God. These immigrants from Ireland were driven from their home by famine. They lie buried here in anonymity, far from the old homes of the heart, but forever short of the new homes of their hopes. They arrived sick and penniless, and took hard and dangerous jobs building the Chicago & Alton Railroad. Their sacrifices made it possible to develop the riches of the land we enjoy today.”

La versione di Stan Hugill

Paddy On The Railway è una canzone marinaresca per il sollevamento dell’ancora o il lavoro alle pompe, trovata in un grande numero di collezioni di canzoni del mare

Dal giornale di bordo del vascello “Young America,” tratta Londra-Moreton Bay, 1864, riportato in C. Fox Smith, “Sailor Town Days” (Methuen, 1923): “Dobbiamo menzionare come peculiare tra le altre strane canzoni che ascoltiamo di notte, una che dovrebbe intitolarsi ‘Pat’s Apprenticeship’, poiché racconta la storia di un certo numero di anni durante i quali il povero Paddy lavora alla ferrovia.”

Paddy On The Railway is a Capstan or pumps shanty finds in a great number of sea song collections.

From the logbook of the vessel “Young America,” from London-Moreton Bay, 1864, reported in C. Fox Smith, “Sailor Town Days” (Methuen, 1923): “We might mention as peculiar amongst the other strange songs that we nightly hear, one which we think must be called ‘Pat’s Apprenticeship,’ as it goes through the history of a number of years during which ‘Poor Paddy works on the railway.'”

Roud # 208

RIFERIMENTI

Sea Songs and Shanties(p67-8),

Songs of Sea Labour(p17),

A Book Of Shanties(p57)

Shanties from the Seven Seas(p252-3)

I

In eighteen hundred and forty one (1)

I put me dungaree (2) breeches on

I put me dungaree breeches on

To work upon the railway the railway,

I’m weary of the railway,

poor Paddy works on the railway.

II

In eighteen hundred and forty-two

I didn’t know what I should do (3)

So I shipped away with an irish crew

to work upon the railway..

III

In eighteen hundred and forty-three

I packed my gear an went to sea

I shipped away to Amerikee

to work upon the railway..

IV

In eighteen hundred and forty-four

I landed on Columbia shore,

I had a pick-axe an’ nothin’ more

to work upon the railway

V

In eighteen hundred and forty-five

when Dan O’ Connelly (4) he was alive

To break me leg I did contrive (5)

to work upon the railway

VI

In eighteen hundred and forty-six

me drinks no longer I could mix (6)

I changed me trade to carrying bricks (7)

to work upon the railway

VII

In eighteen hundred and forty-seven

me children number it’s just eleven

and I’m starting think to sail to Heaven (8)

to work upon the railway

VIII

In eighteen hundred and forty-eight

I made a fortune not too late

an’ shipped away to the River Plate

to work upon the railway

IX

In eighteen hundred and forty nine

I for a sight of Home did pine,

So I sailed down south to a warmer clime (9)

to work upon the railway

I

Nel 1841

mi misi i jeans

mi misi i jeans

per lavorare sui binari della ferrovia, (la ferrovia,

sono stanco della ferrovia,

il povero Paddy lavora alla ferrovia.)

II

Nel 1842

non sapevo cosa fare

così me ne andai con una ciurma irlandese

per lavorare alla ferrovia..

III

Nel 1843

feci il bagaglio e presi il mare

e salpai verso l’America

per lavorare alla ferrovia

IV

Nel 1844

sbarcai sulla spiaggia della Columbia

avevo un piccone e nient’altro

per lavorare alla ferrovia

V

Nel 1845

quando Daniel O’ Connelly era vivo

escogitai di rompermi una gamba

per lavorare alla ferrovia

VI

Nel 1846

non riuscivo più a mescolare i drink

cambiai il mestiere per trasportare mattoni/traversine/e lavorare alla ferrovia.

VI

Nel 1847

il numero dei miei figli arrivò a 11

E iniziai a pensare di salpare per il Cielo

a lavorare alla ferrovia

VIII

Nel 1848

ho fatto fortuna non troppo tardi

sono partito per River Plate

per lavorare alla ferrovia

IX

Nel 1849

avevo nostalgia di casa

così salpai verso sud in un clima più caldo

per lavorare alla ferrovia

FOOTNOTES

from Stan Hugill, 1994, Shanties from the Seven Seas,

1) The Irish Great Famine struck the island of Ireland between 1845 and 1849, causing the death of about one million people and the emigration of a further million abroad.

2) jeans

3) or I had some work that I must do

4) Daniel O’Connell (1775-1847) was an Irish politician and lawyer who started the Repeal Association for the abolition of the Act of Union (between the Kingdom of Ireland and the Kingdom of Great Britain). In particular in 1843 he was imprisoned and released only the following year for having held a series of rallies (followed by a large audience) in which he hoped for the self-government of Ireland. Obviously he never worked on railway yards, but he was one on the workers’ side.

5) or The wonder is I kept alive

7) Has Paddy changed his job and is now a bricklayer, or has he changed the type of work on the railway and is now laying the sleepers? (that is, he is assigned to laying the tracks, the wooden sleepers and the iron rails.)

8) or Of girls I’d four, of boys I’d seven

9) or So I sailed down south to fair Caroline

NOTE Traduzione italiana di Cattia Salto

La Grande Carestia irlandese colpì l’isola d’Irlanda tra il 1845 e il 1849, causando la morte di circa un milione di persone e l’emigrazione all’estero di un ulteriore milione.

2) jeans

3) avevo un lavoro da fare

4) Daniel O’Connell (1775-1847) era un uomo politico irlandese, nonché avvocato che diede vita alla Repeal Association per l’abolizione dell’Atto d’Unione (tra il Regno d’Irlanda e il Regno di Gran Bretagna). In particolare nel 1843 fu imprigionato e liberato solo l’anno successivo per aver tenuto una serie di comizi (seguiti da un folto pubblico) nei quali auspicava l’autogoverno dell’Irlanda. Ovviamente non ha mai lavorato nei cantieri ferroviari, ma era uno dalla parte dei lavoratori.

5) il bello è che ero ancora vivo

6) non so se con il significato di “non potevo più annacquare i miei drink”

7) Paddy ha cambiato lavoro e adesso è un muratore, oppure ha cambiato tipo di lavoro in ferrovia e adesso posa le traversine? (cioè è addetto alla posa dei binari, le traversine di legno e le rotaie in ferro.)

8) or Of girls I’d four, of boys I’d seven [di ragazze ne avevo quattro, di ragazzi ne avevo sette]

9) or So I sailed down south to fair Caroline [così navigai a Sud verso la bella Caroline]

La versione del marinaio John Short: The American Railway

Leggiamo nel Progetto Short Sharp Shanties: “Una dei due canti marinareschi (l’altra è He Back, She Back) che si riferiscono alla canzone americana “Pat Do This”. C’è ovviamente una serie di canzoni, tra cui Pat Do This, Paddy Works on the Erie, Mick Upon on the Railroad, tra i canti delle pinete e della ferrovia americana.

La prima traccia di Paddy Works On The Railway sembra essere del 1864 in un manoscritto del clipper Young Australia. Per complicare ulteriormente le cose, anche Colcord, Terry e Hugill collegano la shanty a “When I Was Just A Shaver” – ma hanno opinioni contrarie su quale sia venuta prima! La maggior parte dei collezionisti offre una versione di questa shanty e, come suggerisce Colcord “La maggior parte delle versioni inizia la carriera di Paddy nel 1841” sebbene alcune inizino nel 1861. A parte questo, le versioni marinaresche variano poco ed evitano la confusione di versi fluttuanti trovati nelle versioni e nelle varianti di terra. Tutti i versetti qui sono da Short. Il suo ultimo versetto, che interrompe la sequenza degli anni, appare anche nella canzone del foglio volante The Press Gang e si ripresenta in forma diversa, insieme alle occupazioni di altri membri della famiglia, in molte altre canzoni fino alle canzoni moderne del rugby“

In the Short Sharp Shanties project they writes: “One of the two shanties (the other being He Back, She Back) which seem to relate to the American shore song Pat Do This . There is obviously a complex of songs, including Pat Do This, Paddy Works on the Erie, Mick Upon on the Railroad, Song of the Pinewoods and The American Railway.

The earliest record of Paddy Works On The Railway seems to be from 1864 in a manuscript from the clipper Young Australia. To complicate things further, Colcord, Terry and Hugill also relate this shanty to When I Was Just A Shaver – but they have contrary opinions as to which was the antecedent of the other!Most collectors give a version of this shanty and, as Colcord suggests, “Most versions begin Paddy’s career in 1841” although some start in 1861. Other than that, the shanty versions vary little and avoid the confusion of floating verses found in shore versions and variants. All the verses here are from Short. His last verse, which breaks the sequence of years, also appears in the broadside song The Press Gang and recurs in variant form, along with the occupations of other family members, in many other songs right down to modern-day rugby songs.

I

In eighteen hundred and forty one (1)

me corduroy (2) britches I put on

with a stiky me face about two feet long

To work upon the railway

(the railway, I’m weary of the railway,

poor Paddy works on the railway.)

II

In eighteen hundred and forty-two

I thought this live could never do

And I resolved to put her through

a-working on the railway

III

In eighteen hundred and forty-three

I paid my passage across the sea

to New York and Amerikee

a-working on the railway

IV

In eighteen hundred and forty-four

I landed on the american shore,

and never to return no more

a-working on the railway

V

In eighteen hundred and forty five

things looked pretty well alive

and I thought to myselfe I’d strive

a-working on the railway

VI

In eighteen hundred and forty-six

when I was in a terrible fix

I thought to myselfe I’d take my sticks (3)

so working on the railway

VII (*)

I had a sister and I was graced

but ??? hugly face

she broke me to a ditty place

a-working on the railway

I

Nel 1841

mi misi i pantaloni di velluto

con un muso lungo due piedi

per lavorare sui binari della ferrovia,

(la ferrovia, sono stanco della ferrovia,

il povero Paddy lavora alla ferrovia.)

II

Nel 1842

pensavo che una vita così non poteva andare,

e decisi di farla finita

di lavorare alla ferrovia..

III

Nel 1843

mi comprai il biglietto per attraversare il mare

verso New York e l’America

per lavorare alla ferrovia

IV

Nel 1844

sbarcai sulla spiaggia d’America

per non ritornare mai più

a lavorare alla ferrovia

V

Nel 1845

le cose sembravano migliorate

e mi sono detto di impegnarmi

per lavorare alla ferrovia

VI

Nel 1846

quando ero in terribile pasticcio

mi sono detto di prendere i miei candelotti (di dinamite)

e lavorare alla ferrovia.

VII

Avevo una sorella ed ero onorato

ma..

NOTE

1) The Irish Great Famine struck Ireland between 1845 and 1849, causing the death of about one million people and the emigration of a further million abroad.

NOTE Traduzione italiana di Cattia Salto

1) La Grande Carestia irlandese colpì l’Irlanda tra il 1845 e il 1849, causando la morte di circa un milione di persone e l’emigrazione all’estero di un ulteriore milione.

2) corduroy= velluto a coste

3) sticks of dynamite [bastoncini di dinamite]

*dell’ultima strofa non comprendo bene la pronuncia delle parole!!

Keith Kendrick in Short Sharp Shanties : Sea songs of a Watchet sailor vol 3

Le versioni americane: “Fil-i-me-oo-re-i-re-ay”, Paddy Works on the Railroad

Paddy On The Railway venne ripresa dagli emigrati irlandesi in America, presenta una grande varietà di strofe abbinate ad un ritornello apparentemente senza senso sulla melodia di Johnny I hardly knew ye.

“Fil-i-me-oo-re-i-re-ay” o “Paddy Works on the Erie” è il titolo di una delle tanti varianti americane (altro testo qui)

Paddy On The Railway taken by Irish emigrants in America presents a wide variety of stanzas combined with a non-sense refrain sung on Johnny I hardly knew ye melody.

“Fil-i-me-oo-re-i-re-ay” or “Paddy Works on the Erie” is the title of one of the many American variants (other text here)

I

In eighteen hundred and forty-one (1)

I put my corduroy (2) breeches on

I put my corduroy breeches on

To work upon the railway

Chorus (3)

Fil-i-me-oo-ree-eye-ri-ay

Fil-i-me-oo-ree-eye-ri-ay

Fil-i-me-oo-ree-eye-ri-ay

To work upon the railway

II

In eighteen hundred and forty-two

I left the old world for the new

Bad cess to the luck that brought me through

To work upon the railway,

III

In eighteen hundred and forty-three

‘twas then I met sweet Biddy McGee

An iligant wife she’s been to me

while workin’ on the railway.

IV

In eighteen hundred and forty four,

me back was gettin’ mighty sore

Me back was gettin’ might sore

while workin’ on the railway

V

In eighteen hundred and forty five

I found meself more dead than alive

I found meself more dead than alive

while workin’ on the railway.

VI

When we left Ireland to come here

And spend our latter days in cheer

Our bosses, they did drink strong beer

And Pat worked on the railway

VII

It’s Pad do this an Pad do that

without a stocking or cravat

Nothing but an ould straw hat

while Pat worked on the railway.

VIII

In eighteen hudnred and forty-six

The gang pelted me with stones and brick.

Oh I was in a hell of a fix

While working on the railway

IX

In eighteen hundred and forty seven,

sweet Biddy McGee she went to heaven

She left one child, she left eleven

to work upon the railway.

I

Nel 1841

mi misi i pantaloni di velluto,

mi misi i pantaloni di velluto,

per lavorare sui binari della ferrovia.

Chorus

Fil-i-me-oo-ree-eye-ri-ay

Fil-i-me-oo-ree-eye-ri-ay

Fil-i-me-oo-ree-eye-ri-ay

lavorare sui binari della ferrovia

II

Nel 1842

lasciai il Vecchio Mondo per il Nuovo,

la mala sorte mi portò

a lavorare sui binari della ferrovia.

III

Nel 1843

fu allora che incontrai Biddy MacGheee

una compagna è stata per me

mentre lavoravo alla ferrovia.

IV

Nel 1844

la mia schiena era a pezzi

la mia schiena era a pezzi

a lavorare sui binari della ferrovia.

V

Nel 1845

ero più morto che vivo

ero più morto che vivo

per lavorare alla ferrovia.

VI

Quando lasciammo l’Irlanda per venire qui

e trascorrere gli ultimi giorni in allegria,

i nostri capi, ci davano birra forte

e Pat lavorava alla ferrovia.

VII

E “Pat fa questo” e “Pat fai quello”,

senza calze e cravatta,

nient’altro che una vecchia paglietta

per lavorare alla ferrovia.

VIII

Nel 1846

la squadra mi bersagliò con pietre e mattoni

ero in un pasticcio infernale

mentre lavoravo alla ferrovia

IX

Nel 1847

la cara Biddy MacGhee andò in paradiso,

se lasciò dei figli, ne lasciò sette

a lavorare sui binari della ferrovia.

FOOTNOTES

1) The Irish Great Famine

3) the seemingly nonsense chorus is actually in Irish Gaelic a sanas-laoi (secret song), Fil-i-me-oo-re-i-rey is the English phonetic spelling of the Irish phrase “fillfidh mé uair éirithe” (pron. Fill’ih may oo-er í-ríheh), which means “I’ll go back, time to get up.”

4) bad cess an Irish expression (qui)

NOTE Traduzione italiana di Cattia Salto

1) La Grande Carestia irlandese

2) corduroy= velluto a coste

3) il coro apparentemente nonsense è in realtà in gaelico irlandese una sanas-laoi (canzone segreta), Fil-i-me-oo-re-i-re-ay è l’ortografia fonetica inglese della frase irlandese ” fillfidh mé uair éirithe ” (pron. Fill’ih può oo-er í-ríheh), che significa “Ritornerò al momento della riscossa”

4) bad cess è un’espressione irlandese (qui)

(I, II, IV, VI, VIII, X)

RIFERIMENTI

Roll And Go(p51),

American Sea Songs and Chanteys (p77-8),

Songs of American Sailormen (p107-8),

The Making of a Sailor (p344-5),

Naval Songs (p6),

Music of The Waters (p35-7),

Chanteying Aboard American Ships (p139-41),

Irish Ballads and Songs of the Sea (p26, 29-30),

An American Sailor’s Treasury (p83-4),

The Way Of The Ship (p104-5),

Shanties from the Seven Seas (p252-3),

Shanties from the Seven Seas (complete)(II) (p336-8)

Poor Paddy Works in California to find gold

Nella versione meno pessimista, il nostro Paddy riesce a fare fortuna con l’oro della California.

In the less pessimistic version, our Paddy manages to make a fortune with the gold of California.

Chorus (1)

Fil-i-me-oo-ree-eye-ri-ay

Fil-i-me-oo-ree-eye-ri-ay

Fil-i-me-oo-ree-eye-ri-ay

To work upon the railway

I

In eighteen hundred and forty-one (2)

My corduroy (3) breeches I put on

My corduroy breeches I put on

To work upon the railway,

II

In eighteen hundred and forty-two

I left the old one for the new

That’s such a love to plot me to

To work upon the railway,

III

In eighteen hundred and forty-three

We hit Chicago what a spree

The devil got a hold of me

To work on the railway

IV

In eighteen hundred and forty-four

I landed on the Columbia shore,

I had a pick-ax and nothing more.

To work on the railway

V

In eighteen hundred and forty five

When Dan O’Connelly (4) was alive,

I worked in a railway hive

To work upon the railway

VI

In eighteen hundred and forty-six

I’d a pain in me ass (5) from carrying bricks

With your hammers a nails and shovels an picks

A working on the railway

VII

It’s Paddy do this an Paddy do that

With bills of stock and our cravat

And nothing but an old silk hat

We’re working on the railway,

VIII

In eighteen hundred and forty-eight

Me hands did bristle and me belly did ache

We hired a boat and made a stake (6)

From working on the railway,

IX

In eighteen hundred and forty-nine

The California hills looked prime

We found some gold and left behind

From working on the railway,

Chorus

Fil-i-me-oo-ree-eye-ri-ay

Fil-i-me-oo-ree-eye-ri-ay

Fil-i-me-oo-ree-eye-ri-ay

lavorare sui binari della ferrovia

I

Nel 1841

mi misi i pantaloni di velluto,

mi misi i pantaloni di velluto,

per lavorare sui binari della ferrovia.

II

Nel 1842

lasciai il Vecchio Mondo per il Nuovo,

e tale amore tramò contro di me

per lavorare sui binari della ferrovia.

III

Nel 1843

ci prendemmo una sbornia a Chicago

e il diavolo s’impossessò di me

per lavorare alla ferrovia.

IV

Nel 1844

sbarcai sulla riva di Columbia

avevo un piccone e nient’altro

per lavorare alla ferrovia.

V

Nel 1845

quando Daniel O’Connell era

vivo, lavoravo in un cantiere ferroviario

per lavorare sui binari della ferrovia.

VI

Nel 1845

mi davo da fare per trasportare mattoni

con martelli e chiodi e badili e picconi

per lavorare alla ferrovia.

VII

E “Pat fa questo” e “Pat dai quello”,

senza calze e cravatta,

nient’altro che un vecchio cilindro,

per lavorare alla ferrovia.

VIII

Nel 1848

le miei mani a pezzi e la mia pancia dolorante, noleggiamo una barca e facemmo da apripista

per lavorare alla ferrovia.

XI

Nel 1849

le colline della California diventarono il numero uno, trovammo l’oro e ci lasciammo alle spalle

il lavoro alla ferrovia

NOTE

1) the seemingly nonsense chorus is actually in Irish Gaelic a sanas-laoi (secret song), Fil-i-me-oo-re-i-rey is the English phonetic spelling of the Irish phrase “fillfidh mé uair éirithe” (pron. Fill’ih may oo-er í-ríheh), which means “I’ll go back, time to get up.”

2) The Irish Great Famine

4) Daniel O’Connell (1775-1847) was an Irish politician and lawyer who started the Repeal Association for the abolition of the Act of Union (between the Kingdom of Ireland and the Kingdom of Great Britain). In particular in 1843 he was imprisoned and released only the following year for having held a series of rallies (followed by a large audience) in which he hoped for the self-government of Ireland. Obviously he never worked on railway yards, but he was one on the workers’ side.

NOTE Traduzione italiana di Cattia Salto

1) il coro apparentemente nonsense è in realtà in gaelico irlandese una sanas-laoi (canzone segreta), Fil-i-me-oo-re-i-re-ay è l’ortografia fonetica inglese della frase irlandese ” fillfidh mé uair éirithe ” (pron. Fill’ih può oo-er í-ríheh), che significa “Ritornerò al momento della riscossa”

2) La Grande Carestia irlandese

3) corduroy= velluto a coste

4) Daniel O’Connell (1775-1847) era un uomo politico irlandese, nonché avvocato che diede vita alla Repeal Association per l’abolizione dell’Atto d’Unione (tra il Regno d’Irlanda e il Regno di Gran Bretagna). In particolare nel 1843 fu imprigionato e liberato solo l’anno successivo per aver tenuto una serie di comizi (seguiti da un folto pubblico) nei quali auspicava l’autogoverno dell’Irlanda. Ovviamente non ha mai lavorato nei cantieri ferroviari, ma era uno dalla parte dei lavoratori.

5) l’espressione è un po’ più colorita di come tradotto, in italiano potrebbe essere “mi rodevo il culo”

6) on a tug? [su un rimorchiatore?]

Wolfe Tones nell’album Across the Broad Atlantic 1976

La versione della ferrovia irlandese

La canzone “Poor Paddy works on the Railway” è forse iniziate come una canzone d’avanspettacolo, la versione irlandese conta 7 anni di lavoro in Inghilterra a partire dal 1841: dalla costa Nord-Est dell’Inghilterra e la città portuale di Hartlepool il protagonista si sposta a Ovest fino alla città ferroviaria di Crewe (all’epoca appena un villaggio di 70 abitanti), nel 1834 si sposta di nuovo a Est per lavorare con la nuova compagnia ferroviaria appena fondata, la Leeds and Selby railway e l’anno successivo ritorna ancora ad Ovest a Liverpool, eppure la pancia di Paddy è sempre vuota e lui è sempre più stanco di andare a lavorare nel cantiere ferroviario e vede come unica soluzione il suicidio!

La versione dei Dubliners è stata ampiamente ripresa dai gruppi irlandesi, e più in generali dai gruppi folk in Inghilterra, aggiunge un ritornello.

The song “Poor Paddy works on the Railway” is pheraps begin as a music hall song, the irish-oriented version has 7 years of work in England since 1841: from the North-East coast of England and the port city of Hartlepool the protagonist moves west to the railway city of Crewe (at the time just a village of 70 inhabitants ), moved back to the east in 1834 to work with the newly founded railway company, Leeds and Selby railway, and the following year returned to Liverpool again in West, yet Paddy’s belly was still empty and he was more and more tired of going to work in the railway yard and seeing suicide as the only solution!

The Dubliners their version largely taken up by Irish groups, and more generally by folk groups in England, adds a refrain.

I

In eighteen hundred and forty one (1)

me corduroy(2) britches I put on

me corduroy britches I put on

to work upon the railway,

the railway, I’m weary of the railway,

poor Paddy works on the railway.

II

In eighteen hundred and forty two

from Hartlepool I moved to Crewe

Found meself a job to do

working on the railway.

Chorus:

I was wearing corduroy britches,

diggin’ ditches, pullin’ switches, dodgin’ hitches (3)

I was working on the railway.

III

In eighteen hundred and forty three

I broke me shovel across me knee,

And I went to work with a company

on the Leeds and Selby railway.

IV

In eighteen hundred and forty four

I landed on the Liverpool shore

Me belly was empty, me hands were raw

with workin’ on the railway,

the railway. I’m weary of the railway,

poor Paddy works on the railway.

V

In eighteen hundred and forty five

when Daniel O’Connell (4) he was alive

When Daniel O’Connell he was alive

and working on the railway.

VI

In eighteen hundred and forty six

I changed me trade from carryin’ bricks (5)

changed me trade from carryin’ bricks

to working on the railway.

VII

In eighteen hundred and forty seven,

poor Paddy (6) was thinkin’ of goin’ to heaven

Poor Paddy was thinkin’ a goin’ to heaven

to work upon the railway, (7)

the railway I’m weary (8) of the railway

poor Paddy works on the railway.

I

Nel 1841

mi misi i pantaloni di velluto ,

mi misi i pantaloni di velluto

per lavorare sui binari della ferrovia,

la ferrovia, sono stanco della ferrovia,

il povero Paddy lavora alla ferrovia.

II

Nel 1842

da Hartlepool andai a Crewe

per trovare un lavoro

e lavorare alla ferrovia

Ritornello:

Indossavo pantaloni di velluto,

scavavo fossi, tiravo carriole, schivavo colpi,

lavoravo alla ferrovia.

III

Nel 1843

mi ruppi il badile sul ginocchio

e andai a lavorare in una compagnia,

la “Leeds and Selby railway”.

IV

Nel 1844

sbarcai sulla spiaggia di Liverpool

la pancia era vuota, le mani erano indurite

dal lavoro alla ferrovia,

la ferrovia, sono stanco della ferrovia,

il povero Paddy lavora alla ferrovia.

V

Nel 1845

quando Daniel O’Connell era vivo,

quando Daniel O’Connell era vivo

e lavorava alla ferrovia

VI

Nel 1846

cambiai lavoro per portare mattoni/traversine,

cambiai il mio lavoro per portare mattoni/traversine

e lavorare alla ferrovia.

VII

Nel 1847,

Il povero Paddy pensava di andare in paradiso,

il povero Paddy pensava di andare in paradiso

per lavorare sui binari della ferrovia,

la ferrovia sono stanco della ferrovia,

il povero Paddy lavora alla ferrovia .

FOOTNOTES

1) The Irish Great Famine struck the island of Ireland between 1845 and 1849, causing the death of about one million people and the emigration of a further million abroad.

3) the initial work of our Paddy was that of a digger, with a pickaxe, shovel and basket: a risky work due to the many accidents that could lead to serious mutilation and death (safety procedures were practically non-existent).

4) Daniel O’Connell (1775-1847) was an Irish politician and lawyer who started the Repeal Association for the abolition of the Act of Union (between the Kingdom of Ireland and the Kingdom of Great Britain). In particular in 1843 he was imprisoned and released only the following year for having held a series of rallies (followed by a large audience) in which he hoped for the self-government of Ireland. Obviously he never worked on railway yards, but he was one on the workers’ side.

5) Has Paddy changed his job and is now a bricklayer, or has he changed the type of work on the railway and is now laying the sleepers? (that is, he is assigned to laying the tracks, the wooden sleepers and the iron rails.)

6) or “old bugger”

7) Is paradise the “reward” for the just, or a place where eternity continues to carry our punishment?

8) or “I’m sick to my death”

NOTE traduzione italiana Cattia Salto

1) La Grande Carestia irlandese colpì l’isola d’Irlanda tra il 1845 e il 1849, causando la morte di circa un milione di persone e l’emigrazione all’estero di un ulteriore milione.

2) corduroy= velluto a coste

3) il lavoro iniziale del nostro Paddy era quello di sterratore, con piccone, badile e cesta: gli spalatori eseguivano gli scavi e scaricavano le carriole di materiale sulla massicciata sotto le precise indicazioni del caposquadra. Il lavoro era anche rischioso a causa dei molti incidenti che potevano portare a gravi mutilazioni e alla morte (le procedure di sicurezza erano praticamente inesistenti). Sono un po’ perplessa nella traduzione di “switches” che tecnicamente significa deviatore può essere quindi sia un interruttore che uno scambio ferroviario. Nel contesto però a me sembra più riferito al lavoro dello sterratore e quindi mi immagino un carretto o una carriola per trasportare terra e pietrame per la massicciata

4) [Daniel O’Connell (1775-1847) era un uomo politico irlandese, nonché avvocato che diede vita alla Repeal Association per l’abolizione dell’Atto d’Unione (tra il Regno d’Irlanda e il Regno di Gran Bretagna). In particolare nel 1843 fu imprigionato e liberato solo l’anno successivo per aver tenuto una serie di comizi (seguiti da un folto pubblico) nei quali auspicava l’autogoverno dell’Irlanda. Ovviamente non ha mai lavorato nei cantieri ferroviari, ma era uno dalla parte dei lavoratori.]

5) Paddy ha cambiato lavoro e adesso è un muratore, oppure ha cambiato tipo di lavoro in ferrovia e adesso posa le traversine? (cioè è addetto alla posa dei binari, le traversine di legno e le rotaie in ferro.)

6) or “old bugger”

7) il paradiso è la “ricompensa” per il giusto, o un luogo in cui per l’eternità si continua a portare la propria pena?

8) or “I’m sick to my death” (in italiano “sono stufo marcio”)

LINK

http://www.traditionalmusic.co.uk/sea-shanty/Paddy_Works_on_the_Railway.htm

http://www.irishmusicdaily.com/poor-paddy-works-on-the-railway

http://ingeb.org/songs/oineight.html

http://www.joe-offer.com/folkinfo/songs/515.html

http://www.joe-offer.com/folkinfo/forum/814.html

http://www.warrenfahey.com.au/poor-paddy-works-on-the-railway/

http://www.deadirishblues.com/song/0

http://mudcat.org/thread.cfm?threadid=79368

http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Page:The_Clipper_Ship_Era.djvu/152

http://history.wiltshire.gov.uk/community/getfolk_print.php?id=425

http://www.grandefrontiera.it/index.php/2016-02-05-16-28-10/1865/19-timeline