Nel 1906 il poeta inglese Alfred Noyes scrive una ballata dal titolo “The Highwayman” il racconto in rima di un tragico amore tra un tenebroso e affascinante bandito di strada settecentesco e Bess (diminutivo di Elisabetta) la bella figlia dai lunghi capelli neri e dagli occhi di stella di un signorotto locale, proprietario terriero inglese o un locandiere (“landlord”). (Versi andati in stampa sul semestrale scozzese “Blackwood’s Magazine”, poi pubblicati in “Forty Singing Seamen and Other Poems” nel 1907)

Una natura romantica con venature gotiche incornicia la storia: è notte con il vento che sibila tra gli alberi e un chiardiluna spettrale.

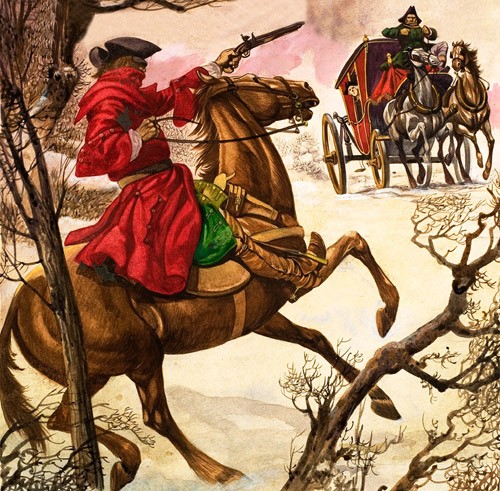

Il bandito di strada della ballata è una creatura letteraria e immaginaria secondo un codice stratificatosi nei secoli a partire dal Medioevo continua

IL SACRIFICIO PER AMORE

Alfred Noyes è considerato un poeta e narratore minore ma molto popolare ancora oggi in Gran Bretagna. “The Highwayman” descrive il sacrificio di Betta, presa come esca dalla soldataglia inglese (legata stretta ad un moschetto ma con la sagoma visibile dalla finestra) che si appostano nella stanza della fanciulla per poter catturare il bandito; il tranello è sventato perchè lei fa scattare il grilletto del moschetto ferendosi mortalmente: il bandito fugge l’imboscata ignaro dell’accaduto, ma all’alba viene a sapere della morte di lei e ritorna sui suoi passi lanciandosi, folle di rabbia, contro il fuoco dei soldati che lo uccidono in strada come un cane. Nella ballata viene anche descritto il traditore dei due innamorati, lo stalliere della tenuta che -come da copione- geloso e infoiato, li denuncia ai soldati.

Alfred Noyes è considerato un poeta e narratore minore ma molto popolare ancora oggi in Gran Bretagna. “The Highwayman” descrive il sacrificio di Betta, presa come esca dalla soldataglia inglese (legata stretta ad un moschetto ma con la sagoma visibile dalla finestra) che si appostano nella stanza della fanciulla per poter catturare il bandito; il tranello è sventato perchè lei fa scattare il grilletto del moschetto ferendosi mortalmente: il bandito fugge l’imboscata ignaro dell’accaduto, ma all’alba viene a sapere della morte di lei e ritorna sui suoi passi lanciandosi, folle di rabbia, contro il fuoco dei soldati che lo uccidono in strada come un cane. Nella ballata viene anche descritto il traditore dei due innamorati, lo stalliere della tenuta che -come da copione- geloso e infoiato, li denuncia ai soldati.

I fantasmi dei due amanti continueranno a incontrarsi per sempre nelle notti di luna piena.

THE HIGHWAYMAN (Alfred Noyes )

I

The wind was a torrent of darkness

among the gusty trees,

The moon was a ghostly galleon

tossed upon cloudy seas,

The road was a ribbon of moonlight,

over the purple moor,

And the highwayman came riding-

Riding-riding-

The highwayman came riding,

up to the old inn-door.

II

He’d a French cocked-hat on his forehead,

a bunch of lace at his chin,

A coat of the claret velvet,

and breeches of brown doe-skin;

They fitted with never a wrinkle:

his boots were up to the thigh!

And he rode with a jewelled twinkle,

His pistol butts a-twinkle,

His rapier hilt a-twinkle,

under the jewelled sky.

III

Over the cobbles he clattered

and clashed in the dark inn-yard,

And he tapped with his whip on the shutters,

but all was locked and barred;

He whistled a tune to the window,

and who should be waiting there

But the landlord’s black-eyed daughter,

Bess, the landlord’s daughter,

Plaiting a dark red love-knot

into her long black hair

[And dark in the old inn-yard a stable

-wicket creaked

Where Tim the ostler listened;

his face was white and peaked;

His eyes were hollows of madness,

his hair like mouldy hay,

But he loved the landlord’s daughter,

The landlord’s red-lipped daughter,

Dumb as a dog he listened,

and he heard the robber say-]

IV

“One kiss, my bonny sweetheart,

I’m after a prize to-night,

But I shall be back with the yellow gold

before the morning light;

Yet, if they press me sharply,

and harry me through the day,

Then look for me by moonlight,

Watch for me by moonlight,

I’ll come to thee by moonlight,

though hell should bar the way.”

V

He rose upright in the stirrups;

he scarce could reach her hand,

But she loosened her hair i’ the casement!

His face burnt like a brand

As the black cascade of perfume

came tumbling over his breast;

And he kissed its waves in the moonlight,

(Oh, sweet black waves in the moonlight!)

Then he tugged at his rein in the moonlight,

and galloped away to the West.

VI

He did not come in the dawning;

he did not come at noon;

And out o’ the tawny sunset,

before the rise o’ the moon,

When the road was a gipsy’s ribbon,

looping the purple moor,

A red-coat troop came marching-

Marching-marching-

King George’s men came marching,

up to the old inn-door.

VII

They said no word to the landlord,

they drank his ale instead,

But they gagged his daughter and bound her

to the foot of her narrow bed;

Two of them knelt at her casement,

with muskets at their side!

There was death at every window;

And hell at one dark window;

For Bess could see, through the casement,

the road that he would ride.

VIII

They had tied her up to attention,

with many a sniggering jest;

They bound a musket beside her,

with the barrel beneath her breast!

“Now keep good watch!”

and they kissed her.

She heard the dead man say-

“Look for me by moonlight;

Watch for me by moonlight;

I’ll come to thee by moonlight,

though hell should bar the way!”

IX

She twisted her hands behind her;

but all the knots held good!

She writhed her hands till here fingers

were wet with sweat or blood!

They stretched and strained in the darkness,

and the hours crawled by like years,

Till, now, on the stroke of midnight,

Cold, on the stroke of midnight,

The tip of one finger touched it!

The trigger at least was hers!

[The tip of one finger touched it;

she strove no more for the rest!

Up, she stood up to attention,

with the barrel beneath her breast,

She would not risk their hearing;

she would not strive again;

For the road lay

bare in the moonlight;

Blank and bare in the moonlight;

And the blood of her veins in the moonlight

throbbed to her love’s refrain.]

X

Tlot-tlot; tlot-tlot! Had they heard it?

The horse-hoofs ringing clear;

Tlot-tlot, tlot-tlot, in the distance?

Were they deaf that they did not hear?

Down the ribbon of moonlight,

over the brow of the hill,

The highwayman came riding,

Riding, riding!

The red-coats looked to their priming!

She stood up strait and still!

XI

((Tlot-tlot, in the frosty silence!

Tlot-tlot, in the echoing night!

Nearer he came and nearer!

Her face was like a light!

Her eyes grew wide for a moment;

she drew one last deep breath,))

Then her finger moved in the moonlight,

Her musket shattered the moonlight,

Shattered her breast in the moonlight

and warned him-with her death.

XII

He turned; he spurred to the West;

he did not know who stood

Bowed, with her head o’er the musket,

drenched with her own red blood!

Not till the dawn he heard it,

his face grew grey to hear

How Bess, the landlord’s daughter,

The landlord’s black-eyed daughter,

Had watched for her love in the moonlight,

and died in the darkness there.

XIII

Back, he spurred like a madman,

shrieking a curse to the sky,

With the white road smoking behind him

and his rapier brandished high!

Blood-red were his spurs

i’ the golden noon;

wine-red was his velvet coat,

When they shot him down on the highway,

Down like

a dog on the highway,

And he lay in his blood on the highway,

with a bunch of lace at his throat.

XIV

And still of a winter’s night, they say,

when the wind is in the trees,

When the moon is a ghostly galleon

tossed upon cloudy seas,

When the road is a ribbon of moonlight

over the purple moor,

A highwayman comes riding-

Riding-riding-

A highwayman comes riding,

up to the old inn-door.

[Over the cobbles he clatters

and clangs in the dark inn-yard,

And he taps with his whip on the shutters,

but all is locked and barred;

He whistles a tune to the window,

and who should be waiting there

But the landlord’s black-eyed daughter,

Bess, the landlord’s daughter,

Plaiting a dark red love-knot

into her long black hair.]

IL BANDITO DI STRADA*

I

Il vento, un torrente di buio,

tra gli alberi squassati,

La luna, un galeone spettrale,

sbattuto su mari di nubi,

La strada, un nastro di chiardiluna.

sulla brughiera purpurea,

E il bandito di strada a cavallo

a cavallo, a cavallo,

E il bandito di strada a cavallo

fino alla porta della vecchia locanda.

II

In testa un tricorno piumato,

merletti fioriti sul mento,

Un manto di velluto scarlatto,

calzoni di daino bruno,

Portati senza neanche una piega;

stivali alti alla coscia! (1)

E cavalcava in uno scintillìo come di gioielli

scintillavano i calci delle pistole

E balenava l’elsa dello stocco

sotto il cielo baluginante.

III

Sui ciottoli scalpitava

nel buio cortile della locanda,

E bussò col suo frustino agli scuri,

ma tutto era chiuso e tangato;

Fischiò un’aria alla finestra, (2)

e chi vi stava a aspettare

Se non la figlia occhineri del padrone,

Bess, la figlia del padrone,

Che intrecciava un vermiglio nodo d’amore

nei suoi lunghi capelli neri.

[Cigolò nel buio la porta di una stalla

nella vecchia locanda

Dove Tim, lo stalliere, ascoltava

col volto pallido e languente;

Con gli occhi scavati di follia,

i capelli come paglia ammuffita,

Ma lui amava la figlia del padrone,

Bess, la figlia del padrone dalle labbra rosse,

E muto come un cane ascoltava,

e udì dire questo al bandito:]

IV

“Un bacio, mia dolce amata,

sto seguendo una preda stanotte,

Ma sarò di ritorno con l’oro lucente

prima della luce del mattino;

Ma se m’incalzeranno dappresso,

e mi tormenteranno durante il giorno,

allora cercami al chiardiluna,

Veglia su di me al chiardiluna,

Verrò da te al chiardiluna,

anche se l’inferno mi sbarrasse la strada (3)”

V

Si alzò dritto sulle staffe;

le arrivava appena alla mano

Ma lei sciolse i capelli alla finestra!

E la faccia gli si incendiò

Quando la nera cascata di profumo

precipitò sul suo petto;

E baciò i capelli ondulati nel chiardiluna,

(Oh, dolci onde nel chiardiluna!)

Poi strattonò le redini nel chiardiluna,

e galoppò lontano a occidente.

VI

Non venne all’albeggiare;

non venne a mezzogiorno;

Né dopo rosso tramonto,

prima del sorgere della luna,

Quando la strada era un nastro gitano

annodato alla brughiera purpurea,

Una truppa dalla giubba rossa

giunse marciando -Marciando, marciando-

Gli uomini del re Giorgio vennero marciando

alla porta della vecchia locanda.

VII

Non dissero parola all’oste;

bevvero invece la sua birra.

Imbavagliarono sua figlia,

e la legarono ai piedi del letto stretto;

Due di loro si sporsero alla sua finestra,

con moschetti al loro fianco!

Vi era morte a ogni finestra;

L’inferno a una scura finestra;

Perché Bess vedeva, attraverso il telaio,

la strada che lui avrebbe cavalcato.

VIII

La legarono sull’attenti,

con molti gesti maliziosi.(4)

Posero un moschetto vicino a lei,

con la canna sul suo petto!

“Adesso, fai buona guardia!”

e la baciarono. (5)

Lei udì il morto (6) dire-

“Cercami nel chiardiluna,

Veglia su di me nel chiardiluna,

Verrò da te nel chiardiluna

anche se l’inferno mi sbarrasse la strada!“

IX

Lei torse le mani dietro di se;

ma tutti i nodi erano saldi!

Torse le mani finché le sue dita

furono madide di sudore o sangue!

Si tesero e sforzarono nell’oscurità,

e le ore si trascinavano come anni,

Finché, allo scoccare della mezzanotte,

Freddo, allo scoccare della mezzanotte,

La punta di un dito lo toccò!

Il grilletto alla fine era suo!

[Lo toccò la punta di un dito;

non si sforzò oltre!

Si alzò all’erta in piedi,

la canna sotto al seno.

Nessun rischio di poter esser sentita,

nessuno sforzo ancora,

Perché la strada stava là,

spoglia nel chiardiluna,

Spoglia e vuota nel chiardiluna;

E nel chiardiluna il palpito delle sue vene

scandiva il suo amore.

X

Tlot-tlot! Avevano sentito?

Gli zoccoli del cavallo suonavano chiari;

Tlot-tlot, in lontananza!

Erano sordi a non sentire?

Lungo il nastro di luna,

oltre il ciglio della collina,

Il bandito venne a cavallo –

Cavalcando, cavalcando

Le giubbe rosse guardarono alle loro armi!

Lei si alzò, dritta e silenziosa.

XI (7)

((Tlot, nel gelido silenzio;

Tlot, nella notte echeggiante!

Più vicino divenne e più vicino ancora.

Il volto di lei era come una luce!

Gli occhi crebbero un istante;

prese un ultimo profondo respiro,))

Poi le sue dita si mossero nel chiardiluna,

Il moschetto infranse il chiardiluna,

Infranse il suo petto nel chiardiluna

e lo avvertì con la sua morte.

XII

Egli si volse. Spronò verso ovest,

non sapeva chi giaceva

Chinata, con la testa sopra il moschetto,

intrisa del suo stesso sangue!

Non lo sentì (8) sino all’alba,

e la sua faccia divenne grigia a sentire

Come Bess, la figlia dell’oste,

La figlia occhineri dell’oste,

Aveva vegliato per il suo amore nel chiardiluna,

e là era morta nell’oscurità.

XIII

E indietro, spronò come un pazzo,

urlando una maledizione al cielo,

Con la bianca strada fumante dietro di lui

e il suo stocco brandito alto.

Rosso sangue erano i suoi speroni

nel mezzogiorno dorato;

rosso vino la sua giacca di velluto;

Quando gli spararono sulla strada maestra,

Lo abbatterono come

un cane sulla strada maestra,

E giacque nel suo sangue sulla strada maestra,

coi merletti fioriti alla gola.

XIV

E ancora dicon che una notte d’inverno

quando il vento squassa gli alberi,

Quando la luna è un galeone spettrale

sbattuto su mari di nubi,

Quando la strada è un nastro di chiardiluna

sulla brughiera purpurea

Dicon che un bandito di strada a cavallo,

a cavallo, a cavallo

Che un bandito di strada arrivi a cavallo

fino alla porta della vecchia locanda.

[Sui ciottoli scalpita

nel buio cortile della locanda,

E bussa col suo frustino agli scuri,

ma tutto è chiuso e tangato;

Fischia un’aria alla finestra,

e chi vi sta a aspettare

Se non la figlia occhineri del padrone,Bess,

la figlia del padrone,

Che intreccia un vermiglio nodo d’amore

nei suoi lunghi capelli neri.]

NOTE

* traduzione italiana di Riccardo Venturi -28/29 gennaio 2008 in Antiwarsongs.org;

nella versione della McKennitt sono state stralciate solo un paio di strofe in particolare quella del traditore che denuncia il bandito perchè innamorato della stessa donna -le strofe omesse non sono numerate e messe tra parentesi quadre

1) è un luogo comune quello del bandito gentiluomo, sempre bello (e ben vestito), abile spadaccino e provetto tiratore, forbito nel parlare e colto, a volte poeta, il prototipo del rubacuori. (cf)

2) il motivetto che il bandito fischietta è il loro codice segreto

3) la frase suona come un giuramento che puntualmente si compie, e il bandito ritorna alla locanda come spirito inquieto nelle notti di luna piena

4) Phil Ochs nella VIII strofa cambia il primo verso

And they bound the landlord’s daughter

5) il poeta non dice ma nella realtà la soldataglia avrebbe violentato prima la fanciulla e poi l’avrebbe legata

6) siamo a metà della ballata, ma il poeta già ci preannuncia che il bandito morirà

7) Phil Ochs riassume la XI strofa

((Look for me by moonlight

Hoof beats ringing clear

Watch for me by moonlight

Were they deaf that they did not hear

For he rode on the gypsy highway

She breathed one final breath))

8) forse in una locanda e tra i soliti brutti ceffi forse anche lo stalliere che l’aveva denunciato

il brano è registrato in Ain’t Marching Anymore [1965]

-affascinato dal tragico finale dei due innamorati che incarnano la gioventù ribelle, schiacciata dalla crudeltà del potere costituito

(Strofe I, III, IV, VI, VIII-var, XI-var, XII, XIII, XIV)

oppure nella clip di Bruno Adams VEDI

con le illustrazioni di Charles Keeping (OUP Oxford; New edition, 1999)

Loreena resta molto aderente al testo e omette solo le strofe messe tra []

I Fleetwood Mac hanno rievocato la vicenda in due occasioni: per scrivere una canzone “The Highwayman” in “Bella Donna” 1981 (album solista di Stevie Nicks) e per il loro corto di “Everywhere in Tango in the Night” (1987) sul testo scritto da Christine McVie (rimasterizzato nel 2017 e pubblicato in formato cd, doppio cd con registrazioni rare e inedite e deluxe)

Can you hear me calling out your name

You know that I’m falling

And I don’t know what to say

I’ll speak a little louder I’ll even shout

You know that I’m pround

And I can’t get the words out

CHORUS

Oh I… I want to be with you everywhere

Something’s happening happening to me

My friends say I’m acting peculiarly

C’mon baby

We better make a start

You better make it soon

Before you break my heart

Can you hear me calling out your name

You know that I’m falling

And I don’t know what to say

Come along baby

We better make a start

You better make it soon

Before you break my heart

Traduzione italiana di Cattia Salto

Riesci a sentirmi mentre invoco il tuo nome?

Lo sai che mi sto innamorando

e non so cosa dire,

griderò un po’ più forte allora urlerò-

lo sai che sono orgogliosa

e non riesco a far uscire le parole.

CORO

Oh io voglia stare con te dappertutto

Sta accadendo qualcosa, capita proprio a me

i miei amici dicono che sono strana,

dai piccolo

è meglio darsi una mossa,

è meglio che ti sbrighi

prima di spezzarmi il cuore

Riesci a sentirmi mentre invoco il tuo nome?

Lo sai che mi sto innamorando

e non so cosa dire

vieni piccolo

è meglio darsi una mossa

è meglio che ti sbrighi

prima di spezzarmi il cuore