GREEN MAN

TRIPLE NATURE OF GREEN MAN

JACK IN THE GREEN MAY MASK

HASTINGS JACK IN THE GREEN FESTIVAL

Jack In the Green (Ian Anderson)

GREEN MAN

Leggi in italiano

The Green Man is an archetypal figure connected with the cycle of nature, it is the immanent green force of Nature. The myth tells of a Goddess, the Mother, who generates her child, but this child is not immortal, and because the cycle of life is renewed, he must die.

His death and rebirth are the regeneration of the Spring and with it the regeneration of the community that celebrates the rite for propitiate fertility.

The Green Man is the guardian spirit of the woods, perhaps an ancient god of vegetation and fertility transversal to many cultures that takes the name of Pan, Cernunnos, Dionysus ..

From the mouth of the Green Man sprouts the rowan twigs with the characteristic red berries. The rowan of the birds, as it is commonly called, represents in the Druidic tradition the rebirth of light after the winter and was therefore considered the tree par excellence of the awakening of Nature.

And yet all this veneration of the past was lost in the Middle Ages when the old gods died and the Green Man became a sort of decorative mask to be understood sometimes as benign but more often as a depiction of the evil one.

TRIPLE NATURE OF GREEN MAN

The deep bond between man and nature is all in the archetype of the green man, the man metamorphosed into a tree. A bond that instills fear but also peace and tranquility hence the ambivalence of the benign or malicious symbol depending on the context: the images smile benevolently or are mocking and fierce. But there is a third type of Green Man: one in which the faces seem scared and suffering.

If some Green Man, instead of joyous, look scary, we find others that, on the contrary, seem scared. These are certainly not demons, but we can not even associate them with images that celebrate the relationship between man and nature. We are faced with another value that this image can take on, that of suffering. In the late Middle Ages, especially after the terrifying experience of the pestilence known as the Black Death, there are rarely joyful and peaceful Green Men. Often branches and leaves stick out of the eyes, in an image that can be terrifying; sometimes the teeth are protruding or very pronounced, as if trying to bite the plant that protrudes from the mouth, to cut it and thus free itself from its suffocating grip. Finally, sometimes we find deformed faces and this too is a very strong signal for the medieval mentality: at that time, in fact, the deformities were a phenomenon much more frequent and known than in the present day, due to insecurity on the places of work, malnutrition and poor care for poor people, and not too advanced medicine. Such incidents in a man’s life were always associated with some divine punishment for his sins. A suffering face that turns into a plant, therefore, puts the accent on the boundary between natural and supernatural, and can sound like a warning against sin and temptations. Another typical representation that can be found is that of Green Man that show the language, probably inspired by the classic Gorgon masks, where it was supposed that this gesture had the sense to drive away evil. It is certain, however, that the people of the Middle Ages did not look at this image in the same way: beyond, in fact, the passages of the Bible that speak of the language as an “unseemly organ”, something that if shown could give rise to scandal, a face with the tongue outside also remembered the image of the hanged man, so certainly not pleasant. (translate from here)

JACK IN THE GREEN the may mask of Middle Ages

In the English folk tradition The Green Man is reborn in a popular May mask of medieval origins (and presumably even more ancient). “Green Jack” was a popular mask of the English May, from the Middle Ages and until the Victorian era, fallen into disuse at the end of the nineteenth century, it returned to show itself and spread to starting from the 1970s in May Day parades.

William Hone in his “The every day book” of 1878 describes the mask of Jack-o’-the-Green “Formerly a pleasant character dressed out with ribands and flowers, figured in village May-games under the name of The Jack-o’-the-Green would sometimes come into the suburbs of London and amuse the residents by rustic dancing.. A Jack-o’-the-Green always carried a long walking stick with floral wreaths; he whisked it about the dance, and afterwards walked with it in high estate like a lord mayor’s footman”

Jack’s mask is further spectacularized by the guild of chimney sweeps, with a boy inside a pyramid-shaped wicker structure, covered with ivy and foliage, surmounted by a kind of wreath of flowers. He went out into the streets with his other friends to dance and collect offers in money. see more

HASTINGS JACK IN THE GREEN FESTIVAL

As well as the other parts of England, the custom was lost in the early twentieth century, but in Hastings (East Sussex, England) the local group of Morris dance, “Mad Jacks” has had the brilliant idea to resume the tradition, mainly organizing a noisy and green festival that lasts a long weekend from Friday to Monday!

The party ends with the symbolic death of Jack in the Green, to remember the ritual sacrifices of Beltane. After centuries still the mystery, wild and disturbing, of the dismemberment of Jack deprived of all the leaves thrown to the crowd!

Songs and dances, drum races, folk music sessions, concerts, follow each other to culminate the last day in the costume parade with the Morris dancers, musicians, chimney sweeps, queens of May, wild men, and green men, to greet the return of Jack, so a long procession is formed behind him, from 10 in the morning until noon where they converges in the stage on the West Hill where among foods, drinks, performances of participants, crafts fair we spend the afternoon for arrive at 4 when Jack is symbolically killed and stripped of his leaves which are thrown to the crowd as a good luck charm.

Ewan Golder & Daniel Penfold movie (The Child Wren’s music), they write in the video notes “Since 1983 folk-lore revivalists have organised the annual Jack In The Green Festival held over the May Day weekend in Hastings. The ‘Jack’, covered head to foot in garlands of flowers and leaves, is paraded through the streets before being ‘ sacrificed’. His death marks the end of winter and the birth of summer. Beltane is the Gaelic name of this festival. The film follows Jack’s journey through the streets of Hastings, to his inevitable demise upon the hilltop.“

JACK IN THE GREEN & Folk music

I have not found real traditional songs about the Green Man, there are many begging songs related to May and just as many that speak of nature that is greening, of blossoming flowers and birds that sing their calls of love.

Anyway, here we go!

Jack in the Green -Ian Anderson

Songs from the Wood, is the musical project by Ian Anderson – front man and green heart of the prog group Jethro Tull – which for the first time walks the path of folk-rock. These are the years of collaboration with the Steeleye Span and the Fairport Convention, when Ian reads the book that his manager gave him “Folklore, Myths and Legends of Brittany”, not least the retirement in the English countryside.

The folk-rock of Ian Anderson, however, is far from the typical repertoire of the 70s, it is instead the English Middle Ages that is at the center of the instrumental arrangements, both in the choice of acoustic instruments and in the vocal harmonizations, and the myths, the rites and the legends of rural folk with a Celtic aftertaste.

I

Have you seen Jack(1)-In-The-Green?

With his long tail hanging down.

He sits quietly under every tree –

in the folds of his velvet gown.

He drinks from the empty acorn cup

the dew that dawn sweetly bestows.

And taps his cane upon the ground –

signals the snowdrops it’s time to grow.

II

It’s no fun being Jack-In-The-Green –

no place to dance, no time for song.(2)

He wears the colours of the summer soldier –

carries the green flag all the winter long.

III

Jack, do you never sleep –

does the green still run deep in your heart?

Or will these changing times,

motorways, powerlines, keep us apart?

Well, I don’t think so –

I saw some grass growing

through the pavements today.

IV

The rowan(3), the oak and the holly tree(4)

are the charges left for you to groom.

Each blade of grass whispers Jack-In-The-Green.

Oh Jack, please help me through my winter’s night.

And we are the berries on the holly tree.

Oh, the mistlethrush is coming(5).

Jack, put out the light.

In Jack in the Green Ian plays pretty much all by himself, the Green Man is a soldier of the summer wrapped in a green velvet frock coat with a walking stick who drinks cups of dew and carries the flag of green beyond winter.

NOTES

1) Jack is the diminutive of two different names James and John, but more than a name right here is to indicate the Green Man

2) the first of May was the feast of Green Jack, with the masks that went around singing and dancing for begging

3) The druids considered the rowan the tree of the Down of the year and it was the symbol of the return of light for its spring rebirth. But they consider most sacred the fruits that they thought were the food of the gods, able to rejuvenate, to prolong life, to satiate and to treat serious wounds. The tree was often planted near houses and stalls to protect them, because it was believed to turn away lightning; if it grew spontaneously close to the houses, it was a bearer of good luck. (translated from here)

4) Holly is a tree with masculine symbology, linked to fraternal love and paternity, the winter counterpart of the Quercia. Sir James George Frazer, in his book “The Golden Bough” and Robert Graves, in “The White Goddess” and “The Greek Myths”, they describe a ritual ceremony that was, according to them, practiced in Ancient Rome and in other more ancient European cultures: the ritual fight between King Holly and King Quercia, a struggle that guaranteed the alternation of winter and summer seasons. (see more)

5) The thrushes and the blackbirds are insensitive to the toxicity of the holly berries and consume large quantities of them becoming the disseminators. The male holly starts to flower when it is about 20 years old and produces small, fragrant white-rosy flowers from May to June. The berries (on the female holly) are green and in autumn they become a shiny red similar to coral: they remain on the tree for the whole winter constituting an important source of food for the birds (be careful because the berries are instead toxic for the man)

LINK

http://www.hastingsjitg.co.uk/

http://terreceltiche.altervista.org/jack-in-the-green-chimney-sweeps-day/

http://www.angolohermes.com/Simboli/Green_Man/Green_Man.html

http://insidetheobsidianmirror.blogspot.it/2013/09/la-vera-natura-delluomo-verde.html

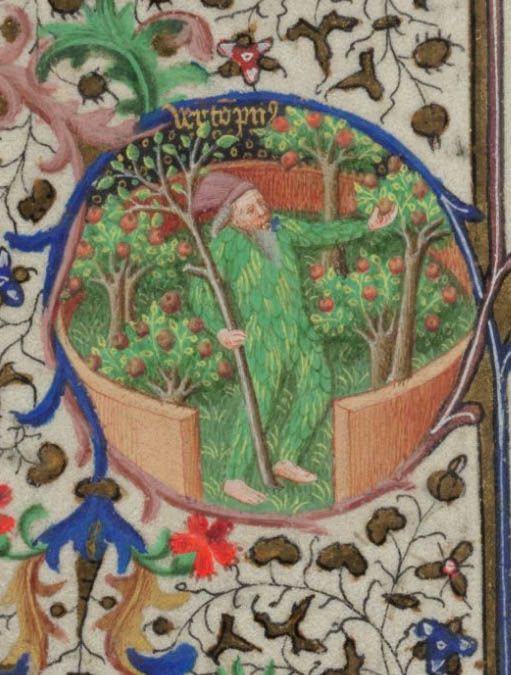

Hello, I am trying to obtain permission to reprint an image on your blog at https://terreceltiche.altervista.org/jack-in-the-green-festival/ (British Library, Add MS 18850, the ‘Bedford Hours’ , Paris XV century) for a book on Ozark folklore. Can you provide that? I can credit your blog. Thanks, Mark Spitzer, [email protected].

Ciao, sto cercando di ottenere il permesso di ristampare un’immagine sul tuo blog all’indirizzo https://terreceltiche.altervista.org/jack-in-the-green-festival/ (British Library, Add MS 18850, ‘Bedford Hours’ , Parigi XV secolo) per un libro sul folklore di Ozark. Puoi fornirlo? Posso accreditare il tuo blog. Grazie, Mark Spitzer, [email protected].

Si tratta del folio 9v del calendario di Settembre https://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/Viewer.aspx?ref=add_ms_18850_f001r -scorri con il cursore fino al mese di settembre [foglio 9v]

immagini ancora più dettagliate in

https://blogs.bl.uk/digitisedmanuscripts/2016/09/a-calendar-page-for-september-2016.html

Le immagini sono fornite nel sito della British Library con uso di pubblico dominio

https://www.bl.uk/help/how-to-reuse-images-of-unpublished-manuscripts#