“Please to see the king” proviene da Pembrokeshire in Galles, ed è tradizionalmente cantato nel giorno di Santo Stefano.

Il re della canzone è il piccolo re, lo scricciolo che viene sacrificato al Boxing Day.

[English translation]

“Please to see the king” comes from Pembrokeshire in Wales, and it is traditionally sung on St Stephen’s Day. The king of the song is the little king, the wren who is sacrificed on Boxing Day.

GALLES : Pembrokeshire

GALLES : Pembrokeshire

IL SACRIFICIO RITUALE DEL RE – MARTIRIO DI SANTO STEFANO

Ancora controversa la questione se i Druidi praticassero sacrifici umani rituali; il dibattito in verità è più orientato sulla questione temporale (i reperti archeologici hanno dimostrato la diffusa presenza di roghi votivi celtici risalenti all’età del bronzo-ferro) ovvero se la prassi fosse ancora praticata dai Galli ai tempi di Giulio Cesare oppure dai druidi irlandesi alle soglie del Medioevo. Un eccezionale reperto archeologico risalente al I-II secolo a. C. è la mummia chiamata l’uomo di Lindow (detto Pete Marsh da qualche giornalista burlone – gioco di parole derivato da “peat marsh”, in italiano “torbiera”) trovato nella torbiera di Lindow Moss, Wilmslow, Contea di Cheshire (Inghilterra).

In occasione delle due principali festività rituali dell’anno (Samahin o Beltane) i Druidi sacrificavano una vittima umana agli dei. La vittima era nutrita con una focaccia d’orzo, denudata e dipinta di rosso, gli veniva legata una striscia di pelo di volpe sul braccio sinistro. Quindi al sorgere del sole gli veniva data la triplice morte, una per la terra, una per l’aria e una per il cielo. La morte era però “pietosa” perchè la vittima veniva tramortita prima con un colpo di mazza, poi era garrotata e quindi gli si squarciava la gola con un coltello ricurvo. Il sangue era raccolto in una coppa d’argento e infine veniva sparso sui campi per garantire un raccolto migliore.

Anticamente era il re ad essere sacrificato, per ottenere i favori degli dei offesi da qualche “scortesia” (ovvero un venir meno nella sua funzione regale): le annate di carestia che si susseguivano, erano un pessimo segnale!

E’ inevitabile il collegamento tra sacrificio dello scricciolo e il martirio del santo, essendo Santo Stefano il primo martire del cristianesimo (protomartire) ucciso per aver testimoniato la sua fede in Cristo. Secondo il folklore irlandese il Santo si era nascosto in un cespuglio di agrifoglio per nascondersi dalla folla che voleva lapidarlo e il suo nascondiglio venne rivelato dallo strepito di uno scricciolo che aveva deciso di svernare proprio lì!

THE RITUAL SACRIFICE OF THE KING – Saint Stephen martyr

The question still arises whether the Druids practiced ritual human sacrifices; the debate in truth is more oriented on the temporal question (archaeological finds have shown the widespread presence of Celtic votive bonfires dating back to the Bronze-Iron Age) or if the ritual was still practiced by the Gauls at the time of Julius Caesar or by the Irish druids on the threshold of the Middle Ages. An exceptional archaeological find dating back to the I-II century a. C. is the mummy called the man of Lindow (called Pete Marsh by some joker journalist – word game derived from “peat marsh”) found in the bog of Lindow Moss, Wilmslow, Cheshire County,England).

On the occasion of the two main ritual festivals of the year (Samahin or Beltane) the Druids sacrificed a human victim to the gods. The victim was nourished with a barley focaccia, stripped and painted red, tied a strip of fox fur on his left arm. So at sunrise it was given the triple death, one for the earth, one for the air and one for the sky. The death was however “pitiful” because the victim was first stunned with a blow of mace, then it was garrotata and then the slashed his throat with a curved knife. The blood was collected in a silver cup and was then spread on the fields to ensure a better harvest.

In ancient times it was the king who was sacrificed, to obtain the favors of the gods offended by some “rudeness” (that is, a lacking in his royal function): the years of famine that followed each other, were a bad sign!

The link between the sacrifice of the wren and the martyrdom of the saint is inevitable, being Saint Stephen the first martyr of Christianity (protomartyr) killed for having witnessed his faith in Christ. According to Irish folklore, the Saint was hiding in a holly bush to hide from the crowd who wanted to stone him and his hiding place was revealed by the noise of a wren who had decided to winter there!

PLEASE TO SEE THE KING

[ Roud 19109 ; Ballad Index FO059 ; DT WRENSONG , WRENSN2 ; Mudcat 28750 ; trad.]

“Please to see the king” o semplicemente “The King” proviene da Pembrokeshire in Galles, ed è tradizionalmente cantato a Santo Stefano.

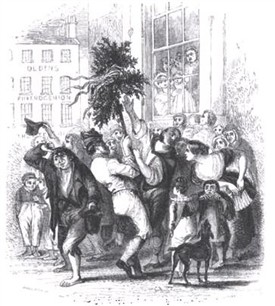

A.L. Lloyd commenta nelle note dell’album dei Watersons in “Sound, Sound Your Instruments of Joy”1977: “Un canto dello scricciolo, cantato da gruppi di ragazzi e giovani, mascherati e travestiti, che il giorno di Santo Stefano (26 dicembre) andavano di porta in porta portando un cespuglio di agrifoglio su cui era messo uno scricciolo morto, “il re degli uccelli “, o qualcosa per rappresentarlo. Questa canzone rara è arrivata ai Waterson da Andy Nisbet, che l’ha presa da “due vecchie signore nel Pembrokeshire“.

“Please to see the king” or “The King” the song comes from Pembrokeshire in Wales, and is traditionally sung on St Stephen’s Day.

AL Lloyd comments in the notes of the Watersons album in “Sound, Sound Your Instruments of Joy” 1977: “A wren-boys carol, sung by groups of boys and young men, masked and disguised, who on St Stephen’s Day (December 26) went from door to door carrying a holly bush on which was a dead wren, “the king of the birds”, or something to represent it. This rare song came to the Watersons from Andy Nisbet, who got it from “two old ladies in Pembrokeshire.”

Salute, amore e pace siano su questa casa,

e con il vostro permesso canteremo del nostro Re.

Il nostro Re è ben vestito con la migliore seta,

con preziosi nastri, nessun re gli si paragona.

Abbiamo viaggiato molte miglia tra siepi e passaggi

alla ricerca del nostro Ree a voi lo portiamo.

Abbiamo polvere e proiettili per prenderne molti

abbiamo cannoni e palle per prenderli tutti.

Il vecchio Natale è passato e la dodicesima notte è l’ultima

e noi vi diamo l’addio, grande gioia per l’anno nuovo!

Traduzione italiana di Cattia Salto

NOTE

1) Una fiaba celtica per bambini racconta la sfida tra l’aquila e lo scricciolo per contendersi l’appellativo di re degli uccelli: avrebbe vinto chi fosse riuscito a volare più in alto! Lo scricciolo partì per primo e quando la possente aquila lo superò si sistemò sul suo dorso e si fece trasportare ancora più in alto, fino a spiccare di nuovo il volo e quindi vincere la gara.

2) manca una strofa allusiva alla gabbietta in cui viene portato lo scricciolo dai wren-boys per mostrarlo alla gente del villaggio: ” Nella sua carrozza è scarrozzato con grande orgoglio, da quattro valletti che vegliano su di lui.”

3) la strofa ha un che di rivoluzionario e senza dubbio è stata cantata anche come canzone di protesta, ma tutto sommato è un po’ una spacconata per dire che il gruppo di wren boys aveva fatto incetta di tutti gli scriccioli del bosco!

4) un tempo i giorni del Natale erano solo 12 e si cominciava a contare dal 21 dicembre di modo che il primo dell’anno era anche l’ultimo delle festività.

IHealth, love and peace Be all here in this place

By your leave we will sing Concerning our king(1).

Our king is well dressed In silks of the best

In ribbons so rare No king can compare.(2)

We have traveled many miles Over hedges and stiles

In search of our king Unto you [him] we bring.

We have powder and shot To conquer the lot

We have cannon and ball To conquer them all.(3)

Old Christmas is past Twelfth tide (4) is the last

And we bid you adieu Great joy to the new.

1) Joe Heaney: And you know how it got the name King of the Birds? The wren — how it came to be called the King of Birds? Well, long ago, there was a big race between all the birds, to see who would fly the highest. And of course the eagle was odds-on favourite to win. And the wren being a little bird, he jumped on the eagle’s back, and of course the eagle never felt him on his back. And the eagle went as high as he could, and he said, “I’m king of the birds!” And the little wren went off his back, up another bit, “No”, he says, “you’re not — I’m king of the birds!” And then the eagle followed him.

2) missing the stanza “In his coach he does not ride with a great deal of pride, and with four footmen to wait upon him”

3) the verse has something revolutionary and no doubt has also been sung as a protest song, but all in all it is exaggerated to say that the group of wren boys had catched all the wrens of the forest!

4) Once the days of Christmas were 12 with the count beginning from 21 December so that the first of the year was also the last of the holidays.