I Fuochi sacri

Firstfoot

Nollick Gennal

Una fetta di Black Bun

HANSELLING: Get Up Goodwife and Shake Your Feathers

Hogmannany

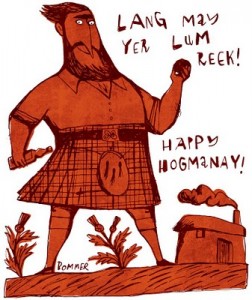

Hogmanay è la festa scozzese di capodanno, dall’origine etimologica incerta, alcuni per le assonanze con il francese “homme est Né”, la fanno risalire alla moda francesizzante imperante nel XVI secolo dalle nozze di Giacomo V di Scozia. Per altri (come ci ricorda Paul Bommer nella sua illustrazione[1]) è una sintesi della frase lum may aye reek o Lang may yer lum reek (=“Possa il tuo camino fumare a lungo!”).

Come sia in Scozia erano e sono i giorni di festa invernale che inizia il 31 dicembre e termina il 2 gennaio, in alcune località tuttavia i festeggiamenti sono traslati all’11 gennaio ossia l’ultimo giorno dell’anno secondo il calendario giuliano.

I FUOCHI SACRI

Molte sono le tradizioni locali connesse con l’accensione di fuochi e falò. Ancora praticata in molte case delle Highlands l’usanza di pulire la casa a fondo, di benedire ogni stanza e gli abitanti con dell’acqua di fiume e di bruciare rami di ginepro per saturare la casa con il fumo, per poi aprire tutte le porte e le finestre e far entrare l’aria del nuovo anno. Si pulivano anche i camini e le stufe dalle ceneri.

L’usanza più diffusa era quella di andare in processione fuori dal villaggio, a volte travestiti o mascherati fino a un cerchio di pietre, se nelle vicinanze, per accendere una grande pira, fare musica e ballare: il fuoco doveva essere alimentato fino al sorgere del nuovo sole del nuovo anno.

[English translation]

Hogmanay is the Scottish New Year’s Eve party, with an uncertain etymological origin, some for the similarities with the French “homme est Né”, they date it to the French-style fashion prevailing in the 16th century from the marriage of James V of Scotland. For others (as Paul Bommer reminds us in his illustration[1]) is a summary of the phrase “lum may aye reek” or “Lang may yer lum reek” (= “May your fireplace smoke for a long time!”).

In Scotland the days of winter festivity begin on December 31 and end on January 2, in some places however the celebrations occour to January 11 that is the last day of the year according to the Julian calendar.

THE SACRED BONFIRES

There are many scottish traditions associated with fires and bonfires. Still practiced in many Highland homes the custom of cleaning the house thoroughly, blessing every room and inhabitants with river water and burning juniper branches to saturate the house with smoke, and then open all the doors and the windows and let the new year’s air enter. It was the time to clean the fireplaces and the stoves from the ashes.

The most common custom was to go in a procession outside the villageup into a circle of stones if nearby, to light a big pyre, make music and dance: the fire had to be fed until the rise of the new sun of the new year.

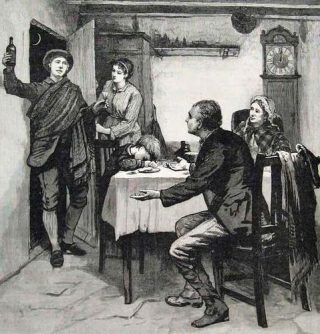

FIRSTFOOT

Si andava a fare visita ai vicini appena dopo lo scoccare della mezzanotte, era consuetudine nel XVIII secolo portare: un uovo, della legna (o del carbone) e un po’ di sale oltre all’immancabile whisky per il brindisi, per augurare tanto cibo, calore, soldi e buon umore

Il firstfoot era occasione di scongiuri: “il primo ospite” doveva essere un uomo alto e scuro di capelli (evidente una volta gli invasori dovevano essere tarchiati e biondi!) perchè avrebbe portato molta fortuna alla casa; ovviamente portavano sfortuna le donne, il medico, il prete, i becchini e chiunque avesse una malformazione o i capelli rossi – il colore delle fate-, e se si apriva la porta ad uno di loro bisognava subito gettare del sale sul fuoco .

Nell’Isola di Man vige un’analoga tradizione e la prima persona a entrare in casa allo scoccare del Nuovo Anno è detto quaaltagh o qualtagh[2]: così un gruppo di giovanotti va di casa in casa a cantare dei versi benaugurali in gaelico e il primo ad entrare deve avere i capelli scuri.

Traduzione italiana Cattia Salto

Un Buon Natale a voi e Buon Anno

Tanta fortuna e salute all’intera casa;

vita, gioia e felicità per tutti.

Pace e amore tra uomini e donne;

buone cose e abbondanza nella dispensa e nella cantina.

Un mucchio di patate e tante aringhe;

pane e formaggio, burro e arrosti.

La morte vi colga come un topo nel formaggio (2)

mentre dormite al sicuro nel vostro letto,

indisturbati dai morsi delle pulci,

e dormite bene.

Nota

(2) Ho preferito tradurre con l’immagina classica del topo nel formaggio piuttosto del “topo nel granaio ben fornito”

Un tempo si cospargeva di cenere la soglia di casa (ma solo dopo aver spazzato bene la casa e pulito il focolare) a scopo divinatorio: “Alla vigilia di Capodanno, in molte delle fattorie dell’altopiano, è ancora consuetudine per la massaia, dopo aver spazzato il focolare per la notte, e appena prima di andare a letto, spargere la cenere sul pavimento, nella speranza di trovarci sopra, la mattina dopo, la traccia di un piede; se le dita di questa inquietante impronta puntano verso la porta, allora, si crede che un membro della famiglia morirà nel corso dell’anno; ma, se il tallone del piede fatato punta in quella direzione, allora, si è certi, che la famiglia crescerà nello stesso periodo.“[3]

They went to visit the neighbors just after the stroke of midnight, it was customary in the eighteenth century to bring: an egg, wood (or coal) and salt in addition to the whisky for the toast, to wish much food, heat, money and good cheer.

“.. firstfoot was to bring gifts to the house: an egg, a faggot of wood, a bit of salt — and a bit of whisky, thus insuring that the household would not lack for necessities during the coming year.” – Diana Gabaldon, “The Fiery Cross” from Outlander series

The firstfoot was an opportunity for knocking on wood: “the first guest” was supposed to be a tall, dark man of hair (once the invaders had to be stocky and blond!) because he would bring much luck to the house; obviously there was bad luck with a woman , the doctor, the priest, the gravediggers and anyone with a malformation or red hair – the color of fairies – (you had to throw salt over the fire immediately!)

In the Isle of Man there is a similar tradition and the first person to enter the house at the stroke of the New Year is called quaaltagh or qualtagh: so a group of young men goes from house to house to sing good-luck verses in Gaelic and the first to enter must have dark hair.

OLLICK GENNAL[2]

From Manx Ballad 1896

(N)Ollick ghennal erriu, as blein feer vie

Seihll as slaynt da’n slane lught-thie;

Bea, gennallys as bioyr eu rv-cheilley.

Shee as graih eddyr mraane’as deiney;

Cooid as cowryn, stock as stoyr.

Palchey puddase as skeddan dy-liooar;

Arran as caashey, eeym as roauyr;

Baase myr lugh ayns ullin ny soalt;

Cadley sauchey tra vees shiu ny lhie,

Gyn feeackle y jiargan, cadley dy mie.

English translation

A Merry Christmas to you, and a good year;

Luck and health to the whole house;

Life, joy, and sprightliness to every one(1).

Peace and love between men and women;

Goods and riches, stock and store.

Lots of potatoes, herring enough ;

Bread and cheese, and butter and beef.

Death like a mouse in a barn haggart (2);

Sleeping safely when you are in bed,

Undisturbed(3) by the flea’s tooth,

sleeping well.

NOTE

1) Literally ” to you together.”

2) The meaning of this is, probably: may death when it comes upon you find you happy and comfortable as a mouse in a well-stocked barn.

3) Literally ” without.”

Once the threshold of the house was covered with ashes for divination purposes:” On New Year’s eve, in many of the upland cottages, it is yet customary for the housewife, after raking the fire for the night, and just before stepping into bed, to spread the ashes smooth over the floor with the tongs, in the hope of finding in it, next morning, the track of a foot ; should the toes of this ominous print point towards the door, then, it is believed, a member of the family will die in the course of that year ; but, should the heel of the fairy foot point in that direction, then, it is firmly believed, that the family will be augmented within the same period.”-“Isle of Man” vol. II p. 115, 1845 Joseph Train [3]

UNA FETTA DI BLACK BUN

Il dolce tipico scozzese per la Festa di Natale è il Balckbun che si cuoce nella forma del pane in cassetta (o uno stampo rettangolare ma anche uno stampo da ciambella), all’esterno è una pasta frolla ma dentro ha il cuore nero ricco di ribes, uvetta e frutta candita! Il ripieno viene inoltre speziato con zucchero scuro, pepe, zenzero e cannella, mandorle e bagnato con il whisky. Anche per questo dolce è essenziale la lunga cottura a bassa temperatura e si prepara in anticipo per lasciarlo insaporire, perfetto per il tè ma anche con un sorso di whisky.

Si mangia a Capodanno ma originariamente era la versione scozzese della “Torta della Mezzanotte” consumata all’Epifania, introdotta da Maria Stuarda dopo il suo ritorno dalla Francia (1560): all’interno dell’impasto era nascosto un fagiolo e chi lo avesse trovato nella sua fetta sarebbe diventato Re (o Regina) della Festa[4].

L’usanza andò presto perduta al seguito dell’abolizione in Scozia della festa del Natale. La Black bun attuale risale perciò ad un tempo relativamente recente e prende il nome di Scotch Bun o Scotch Christmas Bun.

La ricetta storica risale al 1755 nel libro di cucina “A New and Easy Method of Cookery” di Elizabeth Cleland in cui viene chiamata “A Plumb-cake or bun”.

Il termine Black Bun fu probabilmente coniato da Robert Louis Stevenson: “il pane di ribes ora è popolare e si mangia in tutte le famiglie. Per settimane prima della grande mattinata, i pasticceri mostrano mucchi di Scotch bun, una sostanza densa e nera, ostile alla vita, e lune piene di pasta frolla adornate con pezzi di buccia o prugna, in onore della stagione e degli affetti familiari. . ‘ Frae Auld Reekie,’ ‘ A guid New Year to ye a’,’ ‘ For the Auld Folk at Hame,’ sono tra i più favoriti di queste occasioni”

Historical recipe (LA RICETTA STORICA)

Paul Hollywood recipe

Una variante di Dundee detta per l’appunto Dundee cake è invece di forma tonda ed è un impasto lievitato, ricco di burro, mandorle tritate e uvetta sultanina, in cui la Scozia sposa la Spagna (uvetta, mandorle e marmellata e succo d’arancia)

A SLICE OF BLACK BUN

The typical Scottish cake for Christmas is baked in the bread mold (a rectangular or rounded mold): outside it is a short pastry but inside the black bun has a black heart full of currants, raisins and candied fruit! The filling is also spiced with dark sugar, pepper, ginger and cinnamon, almonds and wet with whiskey. For this dessert it is essential the long cooking at low temperature and it is prepared in advance to let it flavor, perfect for tea but also with a sip of whiskey.

It is eaten on New Year’s Eve but originally it was the Scottish version of the “Midnight Cake” consumed at Epiphany, introduced by Maria Stuarda after her return from France (1560): a bean was hidden inside the dough and who had found it in his slice he would become King (or Queen) of the Feast[4].

The custom was soon lost following the abolition of the Christmas revel in Scotland. The current Black bun dates back to a relatively recent time and takes the name of Scotch Bun or Scotch Christmas Bun.

The historical recipe dates back to 1755 in Elizabeth Cleland’s cookbook “A New and Easy Method of Cookery” in which she is called “A Plumb-cake or bun”.

The term Black Bun was probably coined by Robert Louis Stevenson:

“Currant-loaf is now popular eating in all households. For weeks before the great morning, confectioners display stacks of Scotch bun — a dense, black substance, inimical to life — and full moons of shortbread adorned with mottoes of peel or sugar-plum, in honour of the season and the family affections. ‘ Frae Auld Reekie,’ ‘ A guid New Year to ye a’,’ ‘ For the Auld Folk at Hame,’ are among the most favoured of these devices.” (from Picturesque Notes on Edinburgh,1879)

LA RICETTA STORICA

di Mrs. Fraser in “The Practice of Cookery” (1791)

Take half a peck of flour, keeping out a little to work it up with ; make a hole in the middle of the flour, and break in sixteen ounces of butter ; pour in a mutchkin (pint) of warm water, and three gills of yeast, and work it up into a smooth dough. If it is not wet enough, put in a little more warm water : then cut off one-third of the dough, and lay it aside for the cover. Take three pounds of stoned raisins, three pounds of cleaned currants, half a pound of blanched almonds cut longwise; candied orange and citron peel cut, of each eight ounces; half an ounce of cloves, an ounce of cinnamon, and two ounces of ginger, all beat and sifted. Mix the spices by themselves, then spread out the dough ; lay the fruit upon it; strew the spices over the fruit, and mix all together. When it is well kneaded, roll out the cover. Cover it neatly, cut it round the sides, prickle it, and bind it with paper to keep it in shape ; set it in a pretty quick oven, and, just before you take it out, glaze the top with a beat egg.

A Dundee variant called Dundee cake has a round shape and is a leavened dough, rich in butter, minced almonds and raisins, in which Scotland marries Spain (raisins, almonds and jam and orange juice. )

LA RICETTA (in english)

LA RICETTA (in italiano)

HANSELLING: Get Up Goodwife and Shake Your Feathers

Gli adulti andavano di porta in porta cantando e gridando “Hogmanay” per condividere dei piccoli doni del nuovo anno (detti “hansel”) per lo più cibi fatti in casa ovvero dolcetti e torte.

I bambini andavano di porta in porta chiedendo una fetta di Black Bun oppure qualche shortbread, i biscottini al burro, (ricetta) era inoltre questo il giorno in cui ricevevano i regali.

The adults went from door to door singing and shouting “Hogmanay” and sharing small gifts of the new year (called “hansel”) mostly homemade food or cakes.

The children went door to door asking for a slice of Black Bun or some shortbread, the biscuits with butter, (recipe here) this was the day they received the gifts.

Traduzione italiana Cattia Salto

Alzati, comare, e datti una mossa,

non credere che siamo mendicanti;

noi siamo i bambini venuti a cantare,

Alzati e dacci il nostro Hogmanay!

Il mezzo penny di Hogmanay,

mezzo penny, mezzo penny!

Il mezzo penny di Hogmanay,

per augurare il Nuovo Anno

NOTE

(1) letteralmente “scuoti le penne”, sottinteso “della coda” (tail feathers) in senso volgare sta per “muovi il culo”, ma anche “segui il ritmo della danza”

(2) o “rise up”

(3) moneta scozzese introdotta nel Seicento del valore di mezzo penny

La vera e propria festa scocca alla mezzanotte tra gli adulti con la visita di parenti, amici e conoscenti, o di chi si trova solo di passaggio, le case sono infatti aperte a tutti: con bevute abbondanti di whisky e idromele, danze e cibo (formaggi stagionati, pasticci e tante torte – non per niente il giorno viene detto anche cake day-) si rinnova la radicata consuetudine di condivisione comunitaria delle provviste invernali, per iniziare l’anno nell’abbondanza e in compagnia. Una bevanda tipica è l’het pint, la bevanda per il wassail, preparata con birra, whisky, uova, zucchero e una spolverata di noce moscata (ricetta qui)

Get Up Goodwife and Shake Your Feathers[5]

Get up, goodwife, and shake your feathers(1),

And dinna think that we are beggars;

For we are bairns come out to play,

Get up(2) and gie’s our hogmanay!

Hogmanay’s a bawbee(3),

a bawbee, a bawbee,

Hogmanay’s a bawbee

to greet the New Year.

FOOTNOTES

(1) in the vulgar sense is to “move the ass”, but also “follow the rhythm of the dance”

(2) or “rise up”

(3) Scottish coin introduced in the seventeenth century worth half a penny

The real party begins at midnight among adults with the visit of relatives, friends and acquaintances, with the houses open to everyone: with plenty of whiskey and mead, dances and food ( aged cheeses, pies and many cakes – not for nothing the day is also called cake day-) it is renewed the sharing of winter supplies, to start the year in abundance and in company. A typical drink is het pint, the drink for wassail, prepared with beer, whiskey, eggs, sugar and a sprinkling of nutmeg (recipe here)

dagli archivi di Tobar an Dualchais ♬

Hogmannany

Una testimonianza di una canzone per bambini viene da Ewan McVicar: “Mia madre l’ha imparata nel cortile della scuola a Plean vicino a Stirling negli anni ’20. La parola ‘Hogmannany’ non è nei soliti dizionari scozzesi, ma l’ho trovata conosciuta da molti anziani scozzesi delle Terre Basse.

Oggi è Hogmanay, domani è Hogmannany

E sono sceso dalla collina a vedere la mia nonna irlandese

La porterò a un ballo, la porterò a cena

E quando l’avrò portata lì, le metterò il naso nel burro

A testimony of a children’s song from Ewan McVicar: “My mother learned this one in the school playground in Plean near Stirling in the 1920s. The word ‘Hogmannany’ is not in the usual Scots dictionaries, but I have found it known to many older Lowland Scots.”

Today is Hogmanay, tomorrow’s Hogmannany

And ah’m gaun doon the brae tae see my Irish grannie

Ah’ll tak her tae a ball, ah’ll tak her tae a supper

An when ah get her there ah’ll stick her nose in the butter

[1] http://paulbommer.blogspot.it/2011/01/happy-hogmanay.html

[2] OLLICK GENNAL http://www.isle-of-man.com/manxnotebook/fulltext/mb1896/p060.htm

http://www.isle-of-man.com/manxnotebook/manxsoc/msvol16/p135.htm

http://www.mamalisa.com/blog/an-old-nursery-rhyme-for-the-new-year/

[3] https://archive.org/details/historicalstatis01trai

[4] Tutti questi dolci della Dodicesima notte hanno mantenuto una caratteristica arcaica, quella di contenere nell’impasto una monetina o un fagiolo. La moneta stava come segno di buona sorte (a ricordo delle invocazioni per ottenere i favori della Dea dell’Abbondanza), il fagiolo ha invece una valenza più ambigua, ricordo di oscuri rituali che trovavano ancora un eco nell’elezione del Re Fagiolo durante il Natale medievale: è il Re del Disordine dei Saturnalia, ma anche il capro espiatorio che veniva immolato per il bene della comunità, un tributo in sangue agli spiriti della Terra per il Solstizio d’Inverno. https://terreceltiche.altervista.org/fetta-dolce-della-dodicesima-notte/

[5] http://sniff.numachi.com/pages/tiRISEGUDE.html

Illustrazione da http://petitepointplace.tumblr.com/post/136393464385/petitepointplace-in-scottish-and-northern